The story of the looting of $70 million from a group of 28 Michigan cemeteries is a tale of modern-day grave robbers who found buried treasure — not in the ground — but in lucrative funeral trust accounts that thousands of hard-working families had pre-paid decades ago.

It is a study of brazen greed: A trio of con men duping state regulators into approving the purchase of the cemeteries, despite telltale clues that pointed to potential fraud against the dead. The alleged theft prompted a shake-up in the state’s regulatory oversight of public cemeteries. In December 2006, state officials obtained an Ingham County Circuit Court order to seize the properties and appoint a conservator to run them. Previously, they’d removed the state’s top cemetery regulator. In late May, a deal was finally closed to sell the properties for $32 million to a New Jersey operator who owns cemeteries and funeral homes in Indiana.

Also in May, Stephen Gobbo, a lawyer and senior manager at the Michigan Department of Labor & Economic Growth, was appointed to the post of cemetery commissioner to oversee the industry. In addition, legislation to protect cemetery trusts and to strengthen state law covering public cemeteries is making its way through the Michigan House and Senate.

Meanwhile, Clayton Ray Smart, the man at the center of what some officials say is one of the most callous consumer frauds in state history, will soon face trial and a possible conviction that could put him behind bars for the rest of his life.

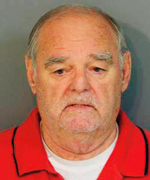

In the fall of 2003, the balding, portly, church-going Smart, a 63-year-old oil-and-gas speculator, blew into metro Detroit from tiny Okmulgee, Okla. A 30-year career National Guardsman who preferred to be addressed as “Colonel,” the rank at which he retired, Smart bragged of his oil fortune and his willingness to make a deal. Even though he had no experience in the industry, Smart offered to buy the state’s largest consortium of 28 cemeteries, resolve chronic complaints from customers, and relieve state regulators of headaches caused by more than a decade of problems with the previous owners of the cemetery group.

The regulators should have looked more closely at the Colonel.

In April 2007, less than three years after Smart bought the cemeteries from companies controlled by Bloomfield Hills attorney Craig Bush, state Attorney General Mike Cox announced an arrest warrant and 39 felony counts against Smart. The attorney general accused Smart of stealing $70 million from merchandise and perpetual-care trust funds that each cemetery must maintain.

State law requires that a portion of every purchase of a cemetery plot be held in a perpetual-care fund. The money can be prudently invested to generate a return to pay for maintaining the grounds and buildings in the future after the cemetery space is sold out. Similarly, as consumers prepay for burials — as well as for opening and closing of graves, or for headstones, vaults, and other funeral items — a portion of the money must be held in a trust by the cemetery to provide those items when they’re needed in the future. Some of the trusts at the oldest cemeteries were established nearly 100 years ago and have accrued millions of dollars. Cemetery operators are allowed to profit from sound, safe investments, but are prohibited by law from touching the principal.

“This was a disgusting theft from the dead of Michigan,” Cox said in announcing the charges against Smart. “He stole money from the dead. The scope of the thefts is staggering; it is absolutely despicable.” Included in the 28 cemeteries are some of the largest and most historic burial properties in metro Detroit. Among them is Woodlawn Cemetery near Woodward and Eight Mile, where many notable Michiganians have been laid to rest: auto magnates Edsel and Benson Ford, and John and Horace Dodge; former Detroit Mayor Albert E. Cobo; and civil rights icon Rosa Parks.

In legal papers filed with Ingham County Circuit Court Judge James Giddings, who is supervising the cemetery case, Cox alleged that immediately after Smart took control of the cemeteries — and the lucrative trust funds — he routed $22 million to Bush to cover the sale price. Records show Bush and Smart signed the sale documents on Aug. 19, 2004. Smart never put up a dime.

While no charges have been brought against Bush, Smart sits today in the Shelby County jail in Memphis, Tenn., where he’s awaiting trial on charges similar to those brought against him by Cox. Tennessee authorities allege that Smart stole more than $20 million from three cemeteries and affiliated funeral homes he purchased in Nashville in 2004. Two associates, Smart’s longtime Oklahoma lawyer Stephen W. Smith, 60, and 41-year-old Mark Singer, a former broker for Smith Barney who has ties to Bush, were also charged in that case.

Smith claims he merely performed legal work, such as drawing up paperwork for Smart. He’s free on a $20,000 bond and is not named in the Michigan case. Singer is free on $1.25 million bail in the Tennessee case. Smart remains in jail and claims he can’t afford a lawyer or his $500,000 bail because Tennessee authorities have frozen his assets. All have denied any wrongdoing and pleaded not guilty in initial court appearances in Tennessee. One of the 39 Michigan felony counts against Smart alleges that he used $4.3 million from the Michigan cemeteries to buy the properties in Tennessee.

Tennessee authorities, who have been more aggressive than their Michigan counterparts in their investigation of Smart, returned their indictments two days before Cox announced the Michigan charges. Smart has yet to be arraigned in 36th District Court in Detroit. Cox said Smart will answer the Michigan charges after the criminal case is concluded in Tennessee.

The fleecing of the cemeteries was set in motion in the early 1990s when the second-largest cemetery-funeral home company in North America, British Columbia’s Loewen Group, came into Michigan and hired Bush as assistant general counsel and its point man to buy up local cemeteries. Because Michigan law prohibits joint ownership of funeral homes and cemeteries, Bush created three corporations, which served as owners of record of Loewen’s acquisitions. As the company closed the sale on each property, the deed was immediately signed over to one of the three corporations.

Over the next few years, Loewen eventually snapped up 28 cemeteries before the company ran into financial and legal trouble, including lawsuits filed in other states due to aggressive business practices. In 1995, the company lost a $500-million predatory business practice case in Mississippi and fell into bankruptcy. In August 2001, Bush, the architect of Loewen’s acquisition of the Michigan cemeteries, wound up with all of Loewen’s ownership after a legal tussle with the sinking company.

Bush’s stewardship of the cemeteries, however, was marked by bitter customer complaints to the state about high-pressure sales tactics, refusals to grant refunds to unhappy customers, newspaper reports of missing trust monies, and sales of burial crypts in mausoleums that were never built. Funeral director Thomas Lynch, a member of the state’s Board of Examiners in Mortuary Science, and who, with six other family members operates six metro Detroit funeral homes, says the state has been grossly negligent in its oversight of the cemeteries.

“The cemetery business is not a great business,” Lynch says. “Every time you use a grave, the inventory goes down and the cost of caring for it goes up. Unlike a nonprofit, churches, or municipal cemeteries, some public cemeteries are platforms for hard-sell pre-selling. [The operators] build up the trust-fund pot and then they pirate them. … That’s been the history of those cemeteries for the 35 years I’ve been a funeral director.”

Amid a flurry of bad newspaper publicity at the time, auditors from the cemetery commissioner’s office within the Department of Labor & Economic Growth began examining the books for some of Bush’s cemeteries in 2003. Bush then announced he intended to sell the properties. At roughly the same time, Clayton Smart arrived on the scene.

While Smart played the part of the successful gas-and-oil wildcatter with Michigan regulators, folks back home in Oklahoma knew better. Although the Colonel incorporated dozens of companies dealing mostly in energy and oil leases, none made much money, according to company filings with Dun & Bradstreet. After failing to repay a $90,000 loan he took out in 1984, Smart filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy in 1988. In divorce proceedings in 1996 from his first wife of 36 years, Smart claimed he had a monthly income of $2,800 despite listing assets worth more than $1 million, which included a 6,000-square-foot house in Okmulgee, east of Oklahoma City.

Reports in the daily newspaper Tulsa World also revealed Smart’s violent side. In 1981, he was convicted of misdemeanor assault and battery after breaking the jaw of a volunteer soccer coach who failed to play his 11-year-old son in the first half of a game. In 1998, his ex-wife, Judith Smart, obtained a protective court order from a judge after she accused Smart of attempting to kill her by choking her and trying to break her neck.

Before making his initial trip to Michigan to negotiate the purchase of the cemeteries, Smart and two associates, Andrew Armstrong and William Leyton, convinced David Strauss and his Houston investment company, Partners in Funding, to loan Smart $5.7 million to help finance the purchase of the Michigan cemeteries. Leyton is a 53-year-old Californian from Hollywood with a law degree and a penchant for using forged documents to back his financial deals. Armstrong, from Tulsa, Okla., was a participant in some of Leyton’s schemes.

The collateral for the loan was a purported $40-million certificate of deposit Smart claimed was on deposit in Leyton’s Strategic Bancorp, an investment company in Beverly Hills, Calif. Strauss didn’t know at the time that Armstrong was under federal investigation for a pension-fraud case in Iowa, while Leyton was involved in a $35-million forgery insurance scam in Florida. Both would eventually be convicted and sentenced to federal prison. Leyton is serving 57 months for wire fraud and forgery. Armstrong drew a 78-month sentence in the Iowa case. Strauss later found out that the $40-million certificate he was holding as collateral was a forgery. When Smart and the two con men refused to pay back the $3.7 million they still owed Strauss, the Texan filed a lawsuit in Houston, which is still pending.

But late in 2003, Strauss believed he was making a potentially lucrative investment in the cemeteries. Strauss flew to Lansing that fall with Armstrong and Smart for a meeting with Bush and Bush’s new financial adviser, Mark Singer — the same Mark Singer who last year was indicted with Smart in Tennessee. Bush set a sale price of $31 million, plus assumption of debt. On Oct. 23, 2003, Smart submitted documents to state cemetery commissioner Suzanne Jolicoeur seeking state approval to buy the cemeteries.

Jolicoeur was a 33-year state employee, and last worked in the Department of Labor & Economic Growth that was reformed under the Granholm administration. The new department oversees more than 30 occupational disciplines, including cemeteries. Jolicoeur supervised the cemetery industry, along with other state-licensed occupations as wildly different as accounting and boxing. It was Jolicoeur’s responsibility to determine Smart’s fitness to be a cemetery operator.

The first clue that should’ve warned her of trouble ahead was in the initial “change of control” application Smart submitted to her office. The general manager Smart listed for the new cemetery company was Wade Reynolds, a veteran cemetery operator from Tennessee. Reynolds, however, had a checkered past. He was banned years earlier from the funeral business by Tennessee authorities amid allegations that he stole money from a cemetery that went bankrupt.

Two months after Smart purchased the cemeteries, he brought Reynolds in as general manager, a move that Jolicoeur did not challenge, even though Reynolds’ background would’ve disqualified him. Reynolds continued in his post, interacting periodically with Jolicoeur on cemetery matters for two years until he returned to Tennessee to run another Smart property. He was under investigation for yet another round of suspected cemetery thefts in Tennessee when he died last year.

Jolicoeur, who now lives out of state, did not return calls to her office to respond to this story. “Whether Suzanne Jolicoeur was feckless, misfeasant, or malfeasant remains to be seen … but that her oversight of the cemetery operations was negligent is indisputable,” says Lynch, of the state’s Board of Examiners in Mortuary Science.

On Feb. 14, 2006, while Smart’s application for a change of control of the cemeteries was being processed in Jolicoeur’s office, Stephen Smith, Smart’s lawyer in Oklahoma, sent a three-page fax to Bush’s lawyer, Sherry Katz-Crank in East Lansing, to demonstrate Smart’s financial ability to buy the cemeteries. Titled “Proof of Ability to Pay,” the fax included a letter to William Leyton from investment broker Carter Green informing Leyton that Green’s company, Hillcrest Capitol Resources Ltd. of Huntington Beach, Calif., was in the process of liquidating a $100-million Federal Reserve certificate to fund a line of credit for one of Smart’s companies. The third page of the fax was a photocopy of the $100-million security certificate.

Like the $40-million certificate given to Strauss, this letter and the photocopied certificate was all a scam. Katz-Crank said she and Bush determined the certificate was phony because the United States Treasury does not issue $100-million certificates. The photocopy was that of a very crude and obvious forgery, as the amount printed on the certificate was misspelled as “One Hundred Million Dollar.”

Katz-Crank said that in a meeting with Bush, Smart, and Jolicoeur, she brought up the matter of the bogus certificate. She said Smart denied he had anything to do with the for- gery, while Jolicoeur showed very little reaction to it. Katz-Crank said she got the impression that the state wanted to see the cemeteries under new ownership, and saw Smart as a white knight. “The state didn’t have any audited financials on the cemeteries; they wanted Bush out, the price was high, and Smart was willing to pay, so they probably didn’t look too closely at Smart,” Katz-Crank says. She adds that she could not explain why Bush would continue dealing with Smart after receiving the bogus letter and $100-million certificate. “It was not my call to continue,” she says.

Through his lawyer, Jeffrey Heuer of Southfield, Bush declined a request to be interviewed. Heuer, however, provided a transcript of court testimony by Leyton in a related criminal case, in which Leyton detailed the cemetery heist he and Armstrong cooked up. Heuer also says the transcript would explain why Bush continued talks with Leyton even after the bogus $100-million scam.

Testifying under oath in a deal with Cox’s office, Leyton also explained the mystery of Smart’s implausible conversion from oil-and-gas speculator to cemeterian. Smart was merely a front for Leyton and Andrew Armstrong, he says.

Leyton testified that in 2003, Armstrong told him about the Michigan cemeteries Craig Bush had put on the market and that Armstrong sent Leyton a due-diligence report on the properties. The cemeteries were attractive because they had good cash flow and had more than $60 million sitting in trust funds. Leyton said Armstrong introduced him to Smart, who would be a party to the purchase. Armstrong was on probation at the time and could not partake in any business deal without a responsible person representing him, and Smart served that purpose, Leyton testified.

What’s more, none of the three participants could match Bush’s $36-million asking price. Leyton testified that through a referral from an acquaintance, he contacted Mark Singer, then an investment broker for Deutsche Bank, and sent him a copy of the due-diligence report on the cemeteries. Leyton testified that Singer called back enthused about the cemeteries and said the bank would underwrite the entire purchase, with one catch: The three partners would have to pass the bank’s vetting process.

Leyton testified he had limited contact with Bush, and that he only spoke with him on a few occasions about the deal. Meanwhile, the bank’s background check came up with negative information on all of the parties, and the deal was terminated, Leyton testified.

At that time, in February 2004, Leyton said he and Carter Green came up with the idea of faxing the bogus letter and photocopy of the forged $100-million certificate to Bush, as well as promoting Smart as a credible buyer. Leyton testified that Bush was livid when he found out the documents were fakes.

“You’re a bunch of thieves, and we’re not going to do business with you,” Leyton quoted Bush as saying in his testimony. Leyton said he had given up on the cemeteries when, weeks later, Singer called him with news that he had left Deutsche Bank, joined Smith Barney, and that Smith Barney would probably finance the purchase. Leyton said he had Singer call Bush about the new development, and Bush agreed to meet with them.

“Craig knew that Mark Singer worked for Smith Barney, knew that he had a position there of authority, and had confidence that this deal might be made,” Leyton testified. In May 2006, three months after they received the photocopy of the bogus $100-million certificate, Bush and Katz-Crank met with Smart and Leyton in an Ann Arbor law office to discuss their proposed purchase of the cemeteries.

The meeting almost broke up as soon as it began. Leyton admitted that his group did not have the $12-million down payment, and that Smith Barney had declined to finance the deal. Bush reacted angrily, and after a few minutes of heated words, Leyton suggested the two of them take a walk outside, Katz-Crank recalled. She said she advised Bush not to talk alone with Leyton, a suggestion he ignored. Bush and Leyton left the room for 10 minutes. When they returned, the meeting broke up. Katz-Crank said she later learned a deal was still in the making.

On Aug. 17, Jolicoeur approved Smart’s application for a change of control of the cemeteries, clearing the way for the sale. Smart bought the cemeteries under the name Indian Nation LLC, a company he incorporated years earlier in Oklahoma. Smart would later change the cemetery group’s name to Mikocem LLC. Two days later, Bush and Smart signed the purchase agreement, with a sale price of $31 million. Smart also agreed to pay off more than $6.5 million in debt owed to Bush. No money changed hands, but the agreement specified that the money was to be wired to Bush by the third business day after the closing.

In an appeal to Judge Giddings in January 2007 to freeze $22 million in a Bush account, three assistant attorneys general conducting the criminal investigation into the funds detailed myriad transactions in which more than $61 million of cemetery funds began flying out of the trust accounts in the weeks after the closing.

Citing interviews with bankers, bank records, and written withdrawal requests signed by Smart or his lawyer, the attorneys general tracked the movement of the monies that went to Smart and to Bush. They also said Bush pressured bank officials to release money to him and to Smart. “There would be no reason for Bush to be pushing bank officials to move the money for Smart unless Bush knew these funds were being used to pay for his (own) interest in the cemeteries,” the attorneys general said in their brief to the court.

Among the transactions they documented: On Aug. 25, six days after he signed off his ownership, Bush contacted LaSalle Bank and directed that $2,442,427 be wired from three cemetery trusts to an account of a corporation he controlled. On Aug. 31, Smart requested another $12 million be wired from LaSalle to his own personal account at Smith Barney. That same day, Bush received a payment of $6,586,637 from the Clayton and Nancy Smart account at Smith Barney, according to the court records.

The court documents cited several other transactions in which millions more were routed circuitously through various accounts until the monies ended up in one belonging to Bush. In response to the request from the attorney general, Judge Giddings ordered that $22 million in a Bush account be frozen until further order by the court. The money remained frozen until Bush offered to return the bulk of it this summer and negotiated a settlement with state-appointed cemetery conservator Mark Zausmer and state officials. While confirming the deal, Zausmer declined to say how much of the money was recovered. Bush’s attorney, Jeffrey Heuer, did not return a call for comment at press time.

The flurry of monies moving out of cemetery accounts in September 2006 drew the attention of a suspicious bank official. Smart was trying to liquidate the trust funds and have the money sent to his personal brokerage account in New York, the banker warned in a note to the state’s cemetery audit manager that was passed on to Jolicoeur. She responded in a letter to the banker (which Smart was copied on) that it was against the law to transfer the trust monies out of state and that the money could only be held in Smith Barney accounts bearing the names of the cemeteries.

No further state action was taken to protect the funds. Within days after Jolicoeur’s letter, Smart directed Singer, the Smith Barney broker, to create 14 new accounts to comply, in part, with Jolicoeur’s directive. Cemetery funds were then transferred into those accounts, and then moved again. “Jolicoeur’s response,” Lynch says, “was like that of a librarian dealing with an overdue book.”

Singer, who lives in an 8,000-square-foot home in New Hope, Penn., has not been criminally charged in Michigan, although he is named in civil lawsuits filed by the state and by cemetery vendors. However, in July, an Indiana grand jury indicted Singer, Sherry Katz-Crank, and an Indiana bank trust officer on five counts of theft of $27 million from Indiana cemeteries. All have denied any wrongdoing.

The bank involved is the same institution Smart allegedly used to wash money from the Tennessee cemeteries. The trio is accused of helping Robert and Debora Nelms steal the money from the cemeteries after Nelms and his wife bought the Indianapolis properties in 2004. The couple was charged in January with multiple counts of fraud and theft. They are now free on bond in that case. Nelms is also under investigation by Michigan authorities in connection with a Grand Rapids cemetery he owns. State auditors said at least $4.2 million is missing from that facility.

In the Michigan case involving Smart, two of the largest amounts of cemetery money ended up in shell companies he controlled or was affiliated with, according to court filings by the attorney general. Some $25 million went to Fondren International, an investment entity registered to Carter Green, the same Leyton ally who had faxed the fake $100-million security note to Bush. According to state audit reports, some $7 million of that money wound up in a hedge fund in the Cayman Islands.

Another $20 million was “loaned” to Quest Minerals and Exploration Inc., a company Smart had incorporated in Oklahoma. In a telephone interview with The Detroit News last year before his arrest, Smart described the Fondren deal as a “sound investment.” He said the Quest transaction did not violate state law prohibiting self-dealing because he had resigned from Quest months before the $20 million was loaned. The current company president, E.L. Huckstep, was a capable businesswoman, he added. Huckstep, however, is the aunt of Smart’s second wife. As it turns out, the 78-year-old Huckstep lives in an old, run-down mobile home in Okmulgee. She has since told authorities Smart had her sign paperwork for Quest and that she had nothing to do with the company. Meanwhile, Federal Aviation Administration records show that, in 2006, a company with connections to Smart purchased an eight-passenger executive jet for $3 million. Later that year, he and his wife bought a $500,000 home in Morris, Okla.

The looting of the funds came to light only after a fired cemetery employee went to the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation in early 2006 with an interesting tale to tell — and hard evidence to back it up. The 34-year-old accountant from Knoxville had been recruited to Detroit by Smart to handle financial records for the cemeteries. Six months after he took the job, he suffered the same fate that befell dozens of other staff members — he was fired in what had become periodic purges at the cemeteries as Smart and his managers churned through employees.

The evidence the accountant turned over to Tennessee investigators was a company laptop computer with the record of the withdrawals on its hard drive. In March 2006, investigators from Tennessee met in Detroit and passed the information about the funds to agents from Cox’s office and cemetery regulators. Seven months later, Jolicoeur was relieved of her duties as cemetery commissioner. She retired from state government shortly afterward and took another job out of state.

In December 2006, state agents raided Smart’s office at the Acacia Park Cemetery on Southfield Road in Beverly Hills and took control of the operations. Soon afterward, Farmington Hills attorney Mark Zausmer was named conservator of the 28 cemeteries. He was able to rescue nearly $5 million of cemetery money he discovered in funds in New York, days before Smart attempted to cash it out.

Last December, Green, 68, who faxed Bush the photocopy of the forged $100-million certificate, became the first person convicted in the case. He was arrested last August after Cox obtained a warrant accusing him of aiding Smart in stealing the funds. Green was charged with conducting a criminal enterprise and three counts of uttering and publishing, and was found guilty in Wayne County Circuit Court. One of the key witnesses against Green was William Leyton, who was brought to court from federal prison as a witness for the attorney general. Green is now serving concurrent sentences of three-to-14 years and 44-months-to-20 years in the Bellamy Creek Correctional Facility in Ionia.