When COVID-19 started roiling through nursing homes last winter, Cecelia Payne had more

at stake than most. And her worst fears soon became reality. Her husband, Arnold Brown, 78, died of COVID-19 on April 24, 2020, at McLaren Macomb Hospital in Mt. Clemens after being transferred there from the Martha T. Berry Medical Care Facility.

Brown, a former manufacturing tooling engineer before a stroke disabled him, had been in the Mt. Clemens skilled nursing facility since 2006. His roommate at the medical care facility died, as well. “I really do feel that he got it from a staff member,” Payne, of Macomb Township, says of her husband’s illness. “Especially when I learned his roommate had it, too.”

Kevin Evans, executive director of the Martha T. Berry Medical Care Facility, says he was saddened by Brown’s death. “I can’t say I’m sorry enough for the loss,” he says, noting the center has had no in-facility coronavirus transmissions since May 2020. “We were doing the best we could in a viral war zone, and we didn’t know enough to be as effective as we are now.”

One year after Gov. Gretchen Whitmer curtailed visits at nursing homes and other senior congregate care facilities across the state, the first of many steps enacted in an attempt to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, what have we learned?

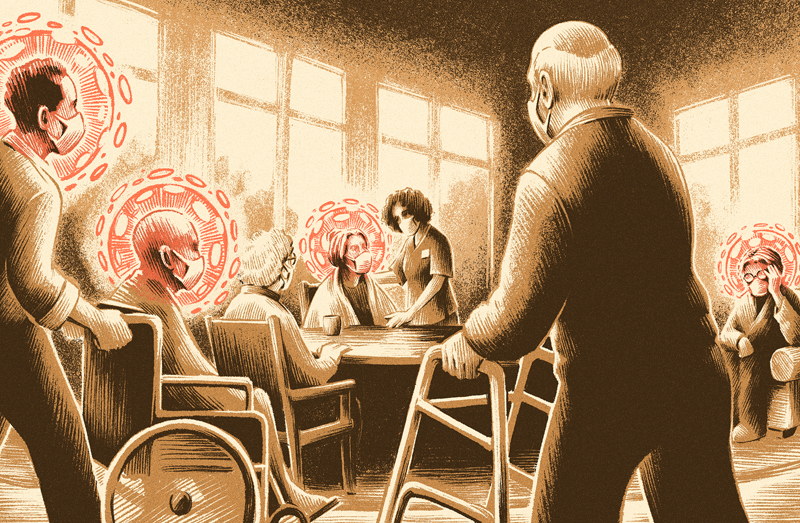

Overall, it’s become abundantly clear that since Whitmer’s executive order was issued last March 14, housing the oldest, sickest, and most frail Michiganders in group settings turned out to be super-spreader setups, and state leaders, along with the people responsible for running and overseeing such residences, were unprepared for a health crisis from a highly contagious, deadly disease.

Three days after the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in the state, Melissa Samuel, president and CEO of the Health Care Association of Michigan, recommended in a letter to the governor, congressional leaders, and department directors that “vacant, and new and unlicensed facilities” be used as “quarantine centers to avoid widespread infection inside of nursing facilities.” A month later, at the direction of an executive order, the state moved to establish a system of regional hub facilities for infected residents.

Overall, 23,620 residents in long-term care settings in Michigan had contracted the virus and more than 5,420 had died from COVID-19 by the end of January. State officials said the numbers include those seniors who died while being treated at hospitals.

As of Feb. 1, deaths in long-term care settings — nursing homes, assisted living, homes for the aged, and adult foster care homes — have accounted for about one-third of the COVID-19 deaths in the state.

It’s not just in Michigan. Nationwide, 40 percent of COVID-19 deaths have occurred in nursing homes, even though they house less than 1 percent of Americans, according to the AARP Bulletin.

Senior care experts say Gov. Whitmer, state health officials, and nursing home operators must do a better job of keeping the elderly in congregate care safe. In fact, the past year has demonstrated that good business practices apply in properly managing senior care facilities just as they do in corporate boardrooms.

Directives need to be clear and comprehensive; leaders must be accountable and deliver on promises; accurate, reliable data is critical to making good decisions; facilities should be run with a high level of service; and any plan’s success depends on scrupulous execution, as even the best strategy will fail when carried out haphazardly.

Former State Rep. Leslie Love can attest to the haphazard execution of good plans. Her mother had been living on a senior continuum-of-care campus for six years when Love testified before the Michigan Senate Oversight Committee last May. Her mother had her own bedroom and bathroom at a Green House home until the campus became a hub facility for COVID-19 patients discharged from hospital care. The hub model, devised by state officials, was created to provide post-acute care for seniors living in congregate care settings that were not equipped for that level of care.

As a result, Love’s mother was transferred out of her private room to another part of the cam-pus, where she was assigned a roommate for the first time. Shortly afterward, the elder Love developed COVID-19. “She had had three negative test results prior (to that), and an X-ray,” Love testified. “I think it is a direct correlation to that mixed environment.”

A better solution would have been to have separate facilities specifically designated for COVID-19-positive people. The second best option would have been to set up separate units with dedicated staff, where “the staff that works with that population only works with that population,” Love said.

It wasn’t until September that Whitmer reacted to the problem by tightening the qualifications for nursing facilities that can accept COVID-positive patients, along with changing their designation from “regional hub” to “care and recovery center.”

Even with guidance from the state and federal government, however, some nursing homes are so poorly run or overwhelmed that it doesn’t seem to make a difference.

For example, state figures from Feb. 1 indicate Lakepointe Senior Care and Rehab Center in Clinton Township had 106 residents test positive for COVID-19, and 34 had died from the virus at the 134-bed facility. At Carriage House Nursing and Rehab in Bay City, which is licensed for 120 beds, 45 residents had tested positive and 11 had died, according to Feb. 1 state figures.

Deanna Mitchell, vice president of health policy for LeadingAge Michigan, a Lansing-based trade association for senior care services, including congregate care facilities, told the Senate Oversight Committee on May 20 that the statewide strategy for stopping the spread of COVID-19 in post-acute and long-term facilities was “quite fragmented” and that coordination needed improvement among state agencies, the governor’s office, and local health departments.

“We have members in several parts of the state who report widely varying guidance from different local health departments, and it’s very unclear when a problem arises in a region who the ultimate agency is for coordinating a resolution,” Mitchell said.

Especially confusing for association members licensed as homes for the aged and adult foster care, neither of which offers the level of medical care nursing homes do, was the lack of guidance from state officials about how to properly care for those seniors who had tested positive for COVID-19.

In the early days of my tenure, we had significant funding to invest in preparedness systems which included disease surveillance … a lot of that funding has waned since 2010. — Janet Olszewski

Unlike nursing homes, which are modeled after hospitals, homes for the aged and adult foster care facilities often lack the resources, skill sets, and structural capacity to dedicate space and personnel for COVID-19 care, Mitchell said. They’re often run as residential homes, and any medical advice would have been very helpful to them.

During an April 21 conference call, Michigan’s Health and Human Services department promised guidance for non-nursing home facilities, but as of May 20 Mitchell still had not received any help.

Meanwhile, in an executive order on April 15, Whitmer established a system of regional hubs among 21 nursing homes the state said were better equipped to isolate and care for COVID-19 patients. “However, almost immediately after the issuance of the order, these facilities had identified that there really wasn’t a real place to put (those patients),” Mitchell said.

Over the following weeks, it became clear to Mitchell’s members that hospitals would only admit patients who needed acute care, while the hubs could accept discharged COVID-19 patients and affected residents from other facilities that couldn’t properly care for them. However, among the 21 facilities selected by the state, nearly half had below-average quality ratings from the federal government.

At the same time, the Whitmer administration paid regional hubs $5,000 per bed in the program, and $200 per day for occupied beds.

Before the pandemic began, Mary Gilhuly thought she had the perfect solution for care

for her mother, Carol, when the 91-year-old family matriarch agreed to move from her Oak Park home to assisted living at St. Anne’s Mead in Southfield.

Things didn’t work out at St. Anne’s after a couple of months, so Gilhuly started shopping for a new place for her mom to live. This time, on the recommendation of a friend, she looked for an adult foster care home.

Gilhuly is one of thousands of Michiganders who needed to find a safe place that’s the right fit for a loved one who can no longer live alone. Difficult to begin with, the task of finding the right place has become harder because of the pandemic’s rampage through congregate senior care locations.

As COVID-19 spread, shopping for a safe place was made especially challenging because of a lack of information from state regulators about incidences of the disease in some senior congregate-care settings, including adult foster care and homes for the aged.

It wasn’t until November that state regulators addressed the problem. The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services began requiring homes for the aged and larger adult foster care facilities to start providing weekly reports on COVID-19 diagnoses and deaths, according to Kate Massey, senior deputy director of the department’s medical services administration.

That was welcome news to Josephine Messelmani, vice president of long-term care services for the Detroit Area Agency on Aging. “Awesome,” she said on hearing the news. “I believe in full transparency, full disclosure.”

There was already a requirement in place for reporting, but compliance was lax. “We’ll be moving toward more enforcement, data validation, and web posting of facility-specific information in the coming weeks,” Massey said in an interview before the change occurred.

Initially, the numbers were incomplete because the state health department had data from only about one-quarter of such congregate care facilities, public information officer Bob Wheaton confirmed. He said the state didn’t have the “bandwidth” to validate all of the data submitted, which they suspected contained errors.

“I think what you see is a public health system that was strained for the appropriate resources to have automated systems in place to collect information and use it,” says Janet Olszewski, who was director of the department from 2003 to 2010, when it was called Community Health for Michigan. “In the early days of my tenure, we had significant funding to invest in preparedness systems which included disease surveillance … a lot of that funding has waned since 2010.”

Compounding the problem were the lower levels of reporting requirements for homes for the aged and adult foster care compared to skilled nursing facilities, she says. “In a pandemic, suddenly a need for their data ramps up and they were like everyone else, suffering from staffing shortages, et cetera.”

Hoping to increase reporting rates, the state has pared down the weekly reporting require-ments from the 40 pieces of information the health department previously required — and often didn’t receive — to just 10 items. “We’re only collecting information that’s relevant and that we would use, and the public might use,” says Erin Emerson, director of the Office of Strategic Partnerships and Medicaid at Michigan’s health department.

As Gilhuly found out when she was shopping for congregate care for her mother, facilities can house anywhere from less than a handful of people to hundreds of individuals in one location. To complicate things, the resident population typically has several COVID-19 risk factors: being 65 and older, lifestyle diseases, and other common late-in-life conditions.

Today, those shopping for a skilled nursing facility can check the state’s health department website for coronavirus diagnoses and COVID-19 deaths at facilities that house the elderly.

Prior to November, those interested in an adult foster care home or a home for the aged were left to do their own research when trying to assess a facility’s safety because the state still hadn’t collected, verified, and put data online from the more than 1,350 congregate care facilities it licenses.

After DBusiness submitted a Freedom of Information Act request, the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services provided some data, even though it was incomplete. As of Aug. 30, the department had received reports of 205 resident coronavirus cases and 39 COVID-19 resident deaths from adult foster care facilities; 451 cases and 186 deaths from homes for the aged; and 179 cases and 82 deaths from assisted living facilities.

Assisted living facilities, which aren’t licensed by the state, are no longer required to report, according to health department spokeswoman Lynn Sutfin.

A clear picture of all that is going on in these facilities is still emerging. For example, Wheaton, Sutfin’s colleague, wrote after the FOIA request was submitted in September: “To piggyback off the FOIA response, I wanted to be sure to let you know that, due to inconsistent reporting by facilities, the data being provided does not paint a complete picture of COVID-19 cases and deaths.”

He said the department knew some facilities weren’t reporting. “For those that are, we haven’t done any true data validation. But given our experience with the nursing home data, we have reason to expect some confusion around data definitions and data quality issues as a result,” he said.

Having complete numbers is important because the public and health departments in Michigan’s 83 counties rely on the state health department for accurate records, according to county public information officers in Macomb and Oakland counties.

Data literacy expert Kristin Fontichiaro, a clinical associate professor at the University of Michigan School of Information in Ann Arbor, likes what she sees at the top of the state health department’s updated long-term care data page, including explanations about data reporting and validation, as well as definitions of the various eldercare licenses. “One thing people (often) do is they look at the chart or the table and don’t realize right away (that they should) look at the meta data (definitions and explanations),” she says. “I think what they’re trying to do is be very clear.”

That doesn’t mean the display couldn’t be improved.

Fontichiaro says it would also be helpful to know how many residents are in one bedroom at each site, and to group together facilities that are in one location. For example, there’s no way of knowing that the skilled nursing facility Care & Rehab Center and Eva’s Place, a home for the aged, both at Glacier Hills Senior Living Community in Ann Arbor, are on the same campus. “I’m not saying the data isn’t accurate,” Fontichiaro says. “I’m saying there are other ways to make it more useful.”

Fontichiaro warns that, sometimes, there can be deliberately misleading data presentations. In Georgia, for example, a graph from the state’s Department of Public Health showed a decline in cases in a bar chart by mixing up times and locations.

On the horizontal x-axis, the graph began on April 28, went back in time to April 27, then jumped two days ahead to April 29, according to Business Insider. The date-hopping continued along the vertical y-axis. The vertical colored bars — with each color representing a county — were arranged in different orders for each date. When examined closely, the graph seemed to bend both time and place to achieve a clean, descending-staircase effect. “I think what we’re seeing is a collision between data and politics,” Fontichiaro says.

Her sentiment resonates with Brian Lee, executive director of Families for Better Care, an advocacy group in Austin, Texas, that’s focused on nursing homes and other long-term care set-tings. He’s tracked data posted across the country and believes pressure from the nursing home industry has prompted some states to keep their numbers hidden.

“It’s about liability protection of an industry more than anything else,” Lee says. “I think it’s a real disservice to the families, and they are desperate for information.” Massey and Emerson, from the Michigan health department, say they haven’t been lobbied by the nursing home industry.

Notwithstanding validation to ensure accuracy, the usefulness of senior congregate care COVID-19 data posted by different states varies.

Florida, for example, the No. 2 state in the nation for percent of population age 65 or older, posts cases and deaths for skilled nursing and assisted living facilities, and for licensed group homes, but Lee says it’s not of very high quality. It’s also hard to get a comprehensive, overall view of COVID-19 in Florida’s congregate care facilities because the data is site-specific or date-specific, with long columns of numbers or bar charts and no totals for either.

“I take it with a grain of salt what they publish,” he says. “There’s a very broad chasm between what Florida is publishing and what CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services) is posting.”

Florida’s numbers were only made more suspect when a state data scientist left her job in May, claiming she was told to report incorrect information. That woman is now facing legal action from the state.

On the other hand, New Jersey has good information, Lee says.

The New Jersey Department of Health publishes a “DATA Dashboard” with information from nursing homes, assisted living, dementia care homes, comprehensive personal care homes, developmental centers, and residential health care facilities licensed by the state. Long-term care data is self-reported daily by the facilities to the department’s Communicable Disease Reporting and Surveillance System, according to an email from a department spokeswoman.

“The COVID-19 dashboard was created by the state Department of Health and first posted March 12 to provide updated, transparent information on cases, hospitalizations, and deaths in long-term care facilities,” she wrote. “It continues to evolve, with the addition of a dashboard on the state’s contact tracing efforts and a dashboard on confirmed outbreaks in K-12 schools.”

While public leaders work to improve their response to the pandemic, Michigan’s health department, like its counterpart in New Jersey, has come up with a plan to make COVID-19 data from adult foster care facilities and homes for the aged more reliable and transparent.

There are still plenty of problems with both procedures and data within congregate care facilities in Michigan, and while it’s too late for the tragic loss of Payne’s husband and other affected seniors, at least people like Gilhuly can now tap out a request on their computer and get some information they need to help keep their loved ones safe.

Care Relief

About 15 years ago, Roger Myers was ready to break ground on a replacement nursing home at the Village of Redford, a retirement community in Redford Township that was part of Presbyterian Villages of Michigan, where he’s president and CEO. He was in his office when a call from the village’s executive director changed the building plans — and Myers’ life.

“Some of my colleagues had heard about these Green Houses in Tupelo, Miss., (so they went there) and they called me from the airport and said, ‘We have to stop everything; we’re about to make a huge mistake,’ ” Myers recalls being told that day. Myers says his colleagues also told him, ‘We’ve seen the future of nursing homes.’“

What the team saw at the Methodist Senior Services Traceway Retirement Community were nursing homes that looked like just that — homes. And that’s just one feature that makes them so different from traditional care facilities.

Traceway’s 10 Green House homes are part of the nonprofit Green House Project, currently a network of 300 radically noninstitutional eldercare environments in 32 states that are designed to look home-like and yet meet regulatory requirements. In a Green House home, each resident, or elder, has a private bedroom and bathroom.

Residents are attended to by a small number of medically qualified universal caregivers who not only help with personal care but also cook, do laundry, clean, and lead activities. In a typical nursing facility, different people from separate departments perform such tasks.

The private, personal accommodations and small number of caregivers may account for the relatively low number of COVID-19 infections in Green Houses nationally, and at the two homes at the Village of Redford that were built according to the new model.

At Green House homes, “… residents are one-fifth as likely to get coronavirus as those who live in typical nursing homes — and one-twentieth as likely to die from the disease it causes,” according to a Nov. 3, 2020, Washington Post article. In the six Green House home campuses in Michigan — Detroit, Grand Rapids, Holland, Kalkaska, Powers, and Redford Township — there were no coronavirus cases at the time of the article’s publication.

In one of the Michigan locations, in Kalkaska, there have been no coronavirus cases among residents throughout the pandemic (as of Feb. 1, 2021).

“I think it’s just less exposure to various people,” says Kelsey Hastings, co-owner of Advantage Management, which owns two Green House homes in Redford Township it bought from Presbyterian Villages. One of the Advantage homes has had no cases of coronavirus among its 10 residents.

Early in the pandemic, at the other Advantage home, a newly admitted person who was positive for the virus died. After his admission, five other residents became sick but recovered. The home has been COVID-19 free since April, Hastings says.

Across town at another Green House location, the Weinberg Residences at the Thome Rivertown Neighborhood in Detroit, six residents among 21 were stricken with the virus early in the pandemic and three died. As understanding of the coronavirus grew, things improved at Weinberg.

“We’ve been COVID-19 free since April, thank God,” says Green House guide Wenona Breazeale. At Green House homes, guides are part of management.

While the Green House homes model typically results in residents who are happier and healthier than people in more traditional facilities, according to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the setup also gives employees a tremendous amount of autonomy, Myers says.

At Weinberg, a group of about 19 universal caregivers, all of them certified nursing assistants, operate as a self-managed work team in charge of its own schedule and job assignments. Their base pay of $14-15 per hour is higher than the $11.50 average hourly wage offered in other long-term care facilities in the area, Breazeale says.

The autonomy and higher pay lead to greater job satisfaction and longevity among staff, which creates more stability and familiarity for the elders, she says.

What is Senior Congregate Care in Michigan?

There are a number of types of congregate care for senior citizens in Michigan. Here’s how the state defines them:

Adult Foster Care

Older residents may need adult foster care services because of the physical frailties of age or mental disabilities. Residents in adult foster care don’t require continuous nursing care unless they’re in hospice. Settings range from homes in neighborhoods to more institutional locations. The state licenses these facilities according to size: congregate homes with more than 20 beds, large group homes with 13 to 20 beds, medium group homes with seven to 12 beds, small group homes with one to six beds, and family homes with one to six beds. COVID-19 data from medium and small group homes isn’t posted online by the state Department of Health and Human Services out of regard for patient privacy.

Assisted Living

Assisted living is strictly a marketing term. Assisted living facilities are not licensed or regulated by the state.

Homes for the Aged

Residents of these types of facilities may need some assistance due to the physical frailties of age. Similar to adult foster care, residents in these homes don’t require continuous nursing care unless they’re in hospice. The term “Home for the Aged” means it’s a supervised personal care facility that provides room and board in addition to supervised personal care (cuing, prompting, reminding or assistance with eating, toileting, bathing, grooming, dressing, transferring, mobility, medical management, keeping appointments, and awareness of a resident’s general whereabouts). These facilities typically house 21 or more unrelated, nontransient individuals 55 years of age or older. Homes for the aged also include supervised personal care facilities for 20 or fewer individuals 55 years of age or older if the facility is operated in conjunction with and as a distinct part of a licensed nursing home. A “room” could be a bedroom, an apartment, or a suite.

Memory Care

There is no license or regulation in Michigan for memory care facilities, which care for people with Alzheimer’s disease and other related illnesses.

Skilled Nursing Facilities

A nursing home is a facility — including county medical care facilities — that provides organized nursing care and medical treatment to seven or more unrelated individuals suffering or recovering from illness, injury, or infirmity. A nursing home, county medical care facility, or hospital long-term care unit that’s state-licensed can be federally certified to participate in Medicare/Medicaid.