In 2003, when former Gov. Jennifer Granholm and Detroit city officials, in lock step with local and state teachers unions, snubbed Bob and Ellen Thompson’s gift of $200 million to build charter schools in the city, the couple from Plymouth found themselves staring at a vast abyss.

The refusal of the offer by a cash-strapped city, burdened by a dysfunctional and underperforming school system, made Detroit the target of national news stories ridiculing local incompetency.

Critics from coast to coast skewered Granholm and then Detroit Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick, along with their respective administrations, for caving to opposition of charter schools by the Detroit Federation of Teachers and the Michigan Education Association, among other labor unions. After union members staged a rally in Lansing in 2003, Kilpatrick and Granholm turned down the Thompsons’ offer in spite of the fact that, earlier, they had welcomed it with open arms.

The political controversy and the fallout the offer ignited was bewildering to the humble, unassuming couple. Only a few years earlier, they had been widely acclaimed when another example of their generosity came to light.

In 1999, Bob Thompson, who owned Michigan’s largest asphalt road-building business, Thompson-McCully Co. in Belleville, sold his holdings to a firm from Ireland for $422 million. He then informed his 550 workers of the sale by letter, and spelled out a special caveat for each of them.

Not only would they keep their jobs, but the Thompsons would share the windfall with all of them. The couple set aside $128 million after taxes for bonuses for their employees. The 80 workers with the most seniority became instant millionaires. They received awards of between $1 million and $2 million each. Hourly workers received $2,000 for each year worked.

Four years later, when the unions and politicians slammed the door on the Thompsons by refusing to work with them, anyone who thought the couple would go quietly into the night misread their determination. To get past the controversy, Bob, a former F-86 Sabre fighter jet pilot, says he constantly harked back to his training days when his instructors taught him to “buy into the mission” and “carry out the mission.”

Today, their dream of boosting Detroit by educating its children is alive and flourishing as more than 4,000 students answer class bells each morning in nine charter schools operating from three different campuses, all funded by the Thompson Education Foundation. Since 2007, the couple has poured more than $126 million into new buildings, retrofitted historic old ones, installed high-speed Internet lines, and outfitted classrooms with equipment and furniture, with more to come.

The foundation has plans for two more elementary schools, and Thompson says he envisions adding at least two more K-12 schools within the next three to five years. Another $100 million was set aside so the foundation could underwrite the charter schools.

For Thompson — who remembered his parents’ painful financial struggles as he grew up poor, without running water or electricity, on the family farm near Hillsdale — the idea of providing Detroit kids with a chance to succeed in life through education was “the mission.”

“Ellen is a teacher and I went to college, but I struggled,” Thompson says. “I’m a bit dyslexic, but college changed my life. When you ask most people how college changed their life, they will give you a pretty positive answer. It may not be necessary for some people, but it’s a high priority for most people. We thought if we could do something, maybe we could change the direction of the city of Detroit.”

Ellen’s stint teaching in an inner-city school gave the couple insight into the challenges some urban children face. “I taught in Highland Park, and I could see the (kids’) needs then, and now the need is much greater than it was years ago,” she says. “We have a passion for education in everything we do. I think it’s the best way to help people.”

The Thompsons aren’t alone. Among those who reached out to the couple following the rebuke from the unions and politicians were Ed Parks, a retired partner at Plante Moran, a large certified public accounting and business advisory firm in Southfield, and Doug Ross, a former candidate for Michigan governor and U.S. assistant secretary of labor in the Clinton administration.

Another valuable ally was former Detroit Mayor Dave Bing, then in private business operating Bing Steel Co. in Detroit. “We really didn’t know what we were doing when we got into it,” Bob says. “Dave helped us navigate through the politics and he took the heat for us. He told us he would be the fall guy and would help us get to where we needed to be.”

Bing, who shares the Thompsons’ aspirations for young people in Detroit, says he was stunned by the union furor and political maneuvering that immediately followed the couple’s $200 million offer.

“Once I learned about the situation, it became apparent to me that here was a guy that was offering help and was turned away for no good reason,” Bing says. “I reached out to Bob and Ellen because I knew how important this was to the children here in the city of Detroit. Here was a guy who was doing it out of the goodness of his heart and wasn’t looking for anything in return. We developed a friendship and I was able to help him get University Prep started.”

The model for that school was already in place. Ross founded the original University Prep Academy in 2000 with 112 students. Thompson was attracted to the school’s “90/90” pledge that promised a 90 percent graduation rate with 90 percent admission to college.

Although Thompson is a Republican, he says he was open-minded to working with Ross, a Democrat.

He believed Ross would put politics aside for the greater good of helping students in Detroit achieve a better future for themselves.

In a story published eight years ago in Hour Detroit, Thompson shared an anecdote from his first meeting with Ross. When Ross picked him up for lunch, Thompson got into the car and Ross warned him there might be chewing gum on the seat. Thompson said he knew Ross’ kids were grown and he didn’t have grandkids, so he asked Ross, “Why would there be chewing gum on the seat?”

Ross replied that if his students don’t show up for school, he would go to their home and get them. “Well, right away I knew this was my guy,” Thompson says.

In addition to providing funding for Ross’ school, the pair spawned the funding of eight other Thompson Foundation schools. And Ross’ 90/90 goal for student performance is still the cardinal goal.

Parks, meanwhile, was instrumental in setting up the administration of the schools under Detroit 90/90, the management organization for the nine schools and three districts. “Ed Parks has been a friend, a counselor, and a support guy for 20 years. His name is on this building,” Bob says, referring to the high school on Antoinette, just south of Henry Ford Health Systems’ headquarters. “Without people like that, you don’t get things done.”

During a recent visit to the campus on Antoinette, Thompson proudly checked off the overall accomplishments of last year’s high school graduating class. Each of the 13 graduating classes in the two high schools, University Preparatory Academy and University Preparatory Science & Math, met the 90/90 graduation college acceptance formula. “We had 319 kids that graduated, 220 of them went on to four-year colleges, 97 went to two-year community colleges, and only two did not make it,” he says. “Just like in business, you have to create outcomes.”

Ellen says the payback they look forward to the most is attending graduation ceremonies and having lunch with the students. “We never miss a graduation,” she says. “It’s just wonderful seeing those young people so full of promise. When we have company from out of town, we bring them down for a visit and to have lunch with the students. That is a real bonus.”

To build on the momentum created by the establishment of the first school, Bob says he recruited his friend, the late A. Alfred Taubman, founder of Taubman Centers Inc. in Bloomfield Hills, to join in the charter effort. The middle and high schools in the Henry Ford Academy: School for Creative Studies are located in the A. Alfred Taubman Center for Design Education (formerly General Motors’ research and technology facility) at Second and Milwaukee. “He told me whenever he was having a really bad day, he would come down to the school and see the kids,” Thompson says. “He offered a lot of great advice, including helping all of the children, not just those with the most potential.”

Thompson says during the three-month enrollment period for new students each winter, the schools do not cherry-pick the applicants. “We aren’t just picking the cream. On average, 11 percent of the students are (academically) challenged,” he says. In addition to accepting applications, the schools round out annual enrollment with a lottery.

Overall, there are 220 teachers working on the three campuses. Each teacher buys into the mission of creating a family-like situation with his or her students, and class sizes are purposely kept low to encourage one-on-one interaction (16 younger students per classroom and 22 students in the upper grades).

Bob says he and his wife are not involved with the administration of the schools, and they don’t back charter schools to make money. He points out that he collects $11 a year for rent on the buildings, and is content to build and outfit the schools and turn them over to professionals. “One thing I learned in life is you have to figure out who you are and who you are not,” he says in explaining why he is not a hands-on landlord.

The Thompson educational blitz is not limited to charter schools in Detroit. They also established hundreds of scholarships for students at Schoolcraft College in Livonia, Michigan Technological University in Houghton, Michigan State University in East Lansing, and Bowling Green State University in Ohio.

As the Detroit schools gained their footing, the successful educational model began to attract people like Mark Ornstein, an educator with a law degree, who was recruited two years ago from the Philadelphia School District to serve as CEO of the Thompson schools.

He says he pulled up his roots and moved to Detroit because the Thompsons impressed him, and he was intrigued by the unique educational situation they helped nurture. “The ability to impact childrens’ lives is a big part of it, and a big part of it is we are in beautiful buildings, and we are in safe buildings,” he says. “All of that is taken care of and we don’t have to worry about that. What we focus on is instruction and providing life experiences for the students. Some of those distractions that happen in education, those things are taken away here.”

Ornstein says operating public charter schools poses financial challenges. The budget for the Thompson schools this year is $16.1 million. While charter schools do not get local funding, they do receive a $7,350 per pupil allocation from the state. That compares with an overall public school contribution of $12,000 to $14,000 per pupil for students living in more affluent school districts like Troy or Rochester.

“We (have a) very lean central management, so there’s not a lot of bureaucracy,” Ornstein says. “We look for alternative means of funding, whether it’s grants or fundraising. We have a development department that works at trying to bridge that gap. We try to create things like international travel, an internship program, and a strong athletic program — frankly, things that cost money. We have generous donors who have supported us significantly over the years and continue to support us.”

He adds that there’s a misconception that the Thompsons subsidize the schools entirely. “They have done an unbelievable job on the buildings, but it stops at the buildings,” he says. “The buildings are turned over to us and we receive no other funding from the Thompsons. If the air conditioner breaks, we have to fix it.”

Despite that, Ornstein says the overall mission remains the same, including maintaining a close student-teacher-parent relationship. “We want teachers to get to know the students and their families,” he says. “If a student is falling through the cracks at a certain point, the teacher has that relationship with the student and the family to pull a flag on the play and say, ‘Hey, Johnny is not acting like himself. What are some of the supports we need to put in place to help him?’ That, in many ways, is at the heart of our organization.”

Competition for skilled teachers is another challenge, especially in math and science. “Many of our teachers who have been with us since the beginning are still with us,” Ornstein says. “It’s not because of the money, but because they believe in the mission and they can see the fruits of their labor with the students’ success.”

Although the vast majority of the schools have achieved their 90/90 graduation-college admission goals, Ornstein acknowledges that, initially, some graduating classes did not fare as well in college. “Those earlier classes, whether they were still in school or graduated, was something like 30 percent,” he says. “The last few years, from the class of 2012 onward, the percentage of students who are still in college is about 82 percent. Those numbers are looking pretty strong.”

For the Thompsons, who celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary in 2015, the progress of the University Prep schools is the culmination of a partnership that began in the 1950s when they met as students at Bowling Green University. Upon graduation in 1956, Bob entered the U.S. Air Force and was commissioned as a lieutenant and trained to fly the prestigious F-86 Sabre fighter jet. The Korean War had ended and the Vietnam conflict was off in the future. “It was a terrific time in our lives,” he says of the three years he was based in Sioux City, Iowa, assigned to the Air Defense Command.

During college, Thompson worked on a road construction crew. After his discharge from the Air Force, he used $3,500 Ellen had saved from teaching to start a road-paving business with his uncle, Wilfred McCully. The partnership didn’t last long, Bob recalls, given McCully wasn’t inclined to take the same kind of aggressive risks as the one-time jet fighter pilot.

Bob says they mortgaged their home six or eight times without worrying about losing the house. He went from a job paving a small section of a street to negotiating with Wayne County and landing a contract to pave a runway at Detroit Metropolitan Airport in Romulus. “Whatever business you’re in, you have to move aggressively,” he says.

A chance early morning breakfast meeting with a stranger in Plymouth served to propel the business through thick and thin, he says. Because he was an early riser, he would quietly slip out of the house so he didn’t disturb his wife, and had breakfast at a downtown dime store on the corner of Main and Ann Arbor Trail.

Another early bird who frequented the diner was Floyd Karror. After a while, the men took notice of each other, exchanged greetings, and began having breakfast together every day. That pattern went on for a year. They made small talk; sometimes it was about farmers, a subject Thompson was intimately familiar with, and sometimes it was about small-business people, whom Karror especially admired.

When Thompson needed to borrow $200,000 to expand his company, he went to the Plymouth Bank and was ushered into the owner’s office. He was surprised to see Karror sitting behind the desk. “At first he said he couldn’t lend me that much money, but then he went out and came back with four certificates, each for $50,000. He told me to go home and have the family sign them.” Thompson’s family at the time consisted of two infant boys and Ellen. With their signatures, and two Xs Bob and Ellen signed for the boys, Thompson got the money. Karror would later sell the bank to the National Bank of Detroit, but continued to run the facility in Plymouth.

“I borrowed tens of millions of dollars from that bank over the years,” Thompson says. “That man gave me my start. You can’t do it alone; you have to have help.”

As the company expanded, it grew into the largest asphalt road-paving operation in Michigan. “We built I-94 and I-275, and eventually we were doing about 68 percent of Michigan roads, from Flint across to Lansing,” he says.

By 1999, Thompson-McCully owned eight asphalt plants, a limestone quarry, and its own asphalt cement storage facility. Two of the plants were in Grand Rapids; there was one each in Kalamazoo, Jackson, and Lansing; and there were three in metro Detroit.

Thompson says stress eventually drove him to sell his business in 1999. After three years of downtime, Thompson got the paving itch again. In 2004, he bought McCoig Materials, a ready-mix concrete company in Wayne, and five years later he purchased a similar outfit, Doan Cos., based in Ypsilanti. Both operations encompass six ready-mix plants in the region with 160 trucks on the road. “We’re doing a lot of work in Detroit,” he says. “We supply a lot of concrete for the new Red Wings arena, and we’re paving Woodward Avenue for the M-1 Rail project.”

>> FIELD TRIP

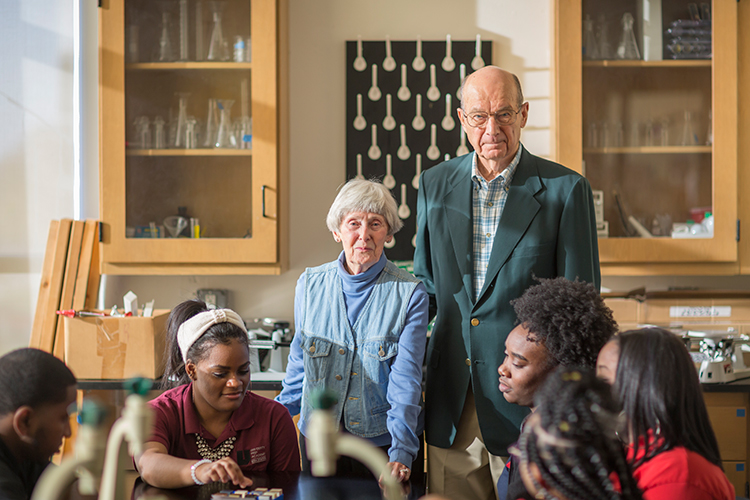

>> FIELD TRIPThe Thompsons visit the UPA High School on St. Antoinette in November. They say competition for skilled teachers is one of the challenges they have in staffing the schools, especially math and science teachers.

Ellen says after 67 years of working six days a week, Bob, at age 83, is cutting back. He gave up working on Saturdays. The couple has three children — John, David, and Anna; six grandchildren; and one great-grandchild.

Looking back, Thompson says the rebuff of his $200 million offer in 2003 worked out best in the long run. “In reality, it wouldn’t have been workable,” he says of teaming up with the Detroit Public School system. “We chose our own path with charters. The teachers we have are unbelievable, and they are at the core of what we do.”

Bing says the Thompsons have performed a great service to the city, and he commends the couple with seeing the larger picture.

“What we have to focus on are the kids and keep politics out of it,” Bing notes. “With the success they’ve had, I don’t think those kids would have done as well in a different environment. I’m a public school kid myself. I believe in public education, but I think our environment has changed over the last 20 years, and there are myriad opportunities that should be available to kids and their parents. Charter schools are here to stay. Fighting charter schools is not the direction we should be going in.”db