Despite a $100 million loss suffered by a Canadian company in its decades-long efforts to open a gold mine in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, a Denver-based mining group is taking on the challenge of tapping into what geologists say are vast underground riches in the Back Forty Mine in Menominee County.

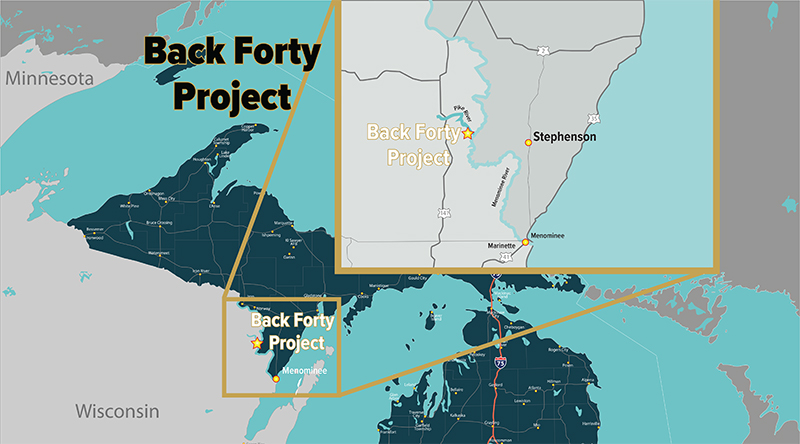

Worn down by battling local opposition both in Michigan and neighboring Wisconsin, and with two Michigan judicial rulings blocking their efforts, in 2021 Aquila Resources Inc. of Toronto threw in the towel after nearly two decades of trying to develop the mine in Lake Township, 15 miles west of Stephenson in the south central section of the U.P.

In December 2021, Aquila completed the sale of the 1,000-acre Back Forty site for $24 million to Gold Resources Corp. (GRC) in Denver, publicly traded as GORO on the New York Stock Exchange.

While gold and silver are the flashy objects drawing the most attention at the mine, geologists believe there are also massive deposits of zinc, copper, and lead buried in the area. Since the last century, geologists have identified the ancient, mineral-rich Penokean Volcanic Belt in the U.P. as a depository for fortunes in gold, silver, and other minerals.

It’s estimated that the site contains 468,000 ounces of gold worth $259 million; zinc deposits of 512 million pounds; up to 86 million pounds of copper; 6.26 million ounces of silver; and 26 million pounds of lead.

This latest gold rush in the U.P. was touched off in 1999 by a local landowner who was deepening the well at his retirement home. Drillers brought up rock containing substances that turned out to be zinc and copper. Further exploration found the presence of gold and silver.

Unlike Aquila, which specializes in the acquisition, exploration, and development of mineral properties, GRC is no amateur when it comes to mining; the company owns the successful Don David Gold Mine in Oaxaca, Mexico.

The president and CEO of GRC, Allen Palmiere, has spent more than 35 years working the financial and operational aspects of mining worldwide. His experience covers mining in South Africa, Central America, Guyana, and Brazil, as well as 10 years in China.

According to its second quarter 2022 financial report, Gold Resources had net sales of $37 million in gold, silver, zinc, copper, and lead from the Mexican mine. The company reported a cash balance of $33 million after investing $15 million in capital improvements and exploration. Of that amount, $3.1 million was spent on new feasibility studies and permitting for the Back Forty Mine.

Palmiere, who is Canadian, is aware of the history and the nature of the opposition to the Back Forty Mine and is determined not to imitate Aquila.

“The days of mining companies coming in and building a mine and totally ignoring their neighbors and doing whatever they want is long since over,” he says.

The major problems Aquila couldn’t overcome include the location of its sulfide ore mine site — 50 yards from the banks of the Menominee River — and the 2,000-foot by 2,500-foot open pit on the river, in which the ore would be processed with toxic chemicals.

Gold, silver, and the other materials would be extracted from the rock and ore using chemicals like sodium cyanide and mercury. The resulting residue, known as tailings — a toxic, slurpy mixture in the open pit — would be left exposed to the Menominee River, one of the largest and most important natural water systems in Michigan. The river basin drains more than 4,000 square miles of the U.P. and northern Wisconsin, and separates Michigan from Wisconsin.

Another flash point was the fate of River Road, which runs beside the waterway and above the ore body. Aquila proposed digging up the road, a move that was vehemently opposed by Lake Township officials and the Menominee Road Commission.

The most emotionally charged opposition, however, comes from the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin, for whom the river is a sacred religious and cultural site. The five clans of the Menominee Nation trace their creation to the mouth of the river. The tribe says the mine site sits on their ancestral homeland, which was ceded to Michigan in the Treaty of 1836, and is home to numerous sacred sites and burial mounds up and down the Menominee River.

The switch from Aquila to GRC doesn’t impress tribal Chairman Ronald J. Corn Sr. “The Menominee were not afforded the opportunity to give our free, prior, and informed consent as to the siting of the mine, nor its impacts on the land, plants, and wildlife which form the body of our cultural traditions and modern cultural practices,” Corn said in a release. “As such, it is our firm position that the Back Forty Mine still lacks the social license to operate regardless of who the developer of the mine happens to be.”

Supporting Corn’s position is the National Congress of American Indians, the oldest and largest American Indian and Alaska Native organization, founded in 1944. The 12 tribes in the United Tribes of Michigan also oppose the mine.

Palmiere says he has and will continue to make efforts to reach out to the Menominee Tribe. He’s awaiting a response to a letter he recently sent to Chairman Corn. In the meantime, the mine’s feasibility study is being revised to address the concerns of tribal members and their supporters, he says.

Included in the changes GRC is proposing is moving the mine eastward 150 yards, to a spot 200 yards away from the river. That move would also leave River Road intact, he says. The handling of the tailings pit waste is also being addressed.

“The tailings pit we’re proposing is much smaller and most of the mining processing will be underground,” Palmiere says. “The tailings pit will be 15 percent to 20 percent smaller, and much shallower that the one Aquila proposed.”

The toxic tailings waste won’t be left in a pond to degrade, Palmiere adds.

“We employ a dry stack method where we filter the water out of it and the dry material is stacked, and as we raise it into a hill, we cap it and seal it with topsoil and vegetate it,” he says. “When it’s grown in, it will look like other hills around it. What little water that remains we will treat and dispose of. This is a much better way of treating tailings, and it’s the method we use at our gold mine in Mexico.”

Another significant change is reducing the size of wetlands impacted from the 26 acres in Aquila’s plan to less than an acre of what Palmiere refers to as “identifiable” wetlands. The disruption of wetlands was the issue that harpooned Aquila’s effort to obtain operating permits from the State of Michigan. It was also the issue on which an administrative law judge in Haslett, and an Ingham County Circuit judge in Lansing, ruled against Aquila.

Palmiere says Gold Resources projects that its feasibility study will be ready for submission to the state early this year. Allowing another eight to 12 months for the permitting process, and a similar amount of time for possible court challenges, work could begin on the Back Forty Mine in two years, he predicts.

Previous estimates, including one by Aquila, put the cost of the buildout at $294 million. Palmiere said he doesn’t yet know what the cost will be, as his team is significantly revising the project.

“There’s a sort of rule of thumb that you need 40 percent by way of equity and 60 percent by way of debt, and given our very robust cash flow coming from Mexico, cash on hand, and additional sources, we feel very confident we will be able to fund this project with our internal finances and financing from a third-party lender,” he says.

The mine project has the support of some state lawmakers, including Sen. Wayne Schmidt (R-Traverse City). In 2022, state Sens. Ed McBroom (R-Vulcan), along with Reps. Beau LaFave (R-Iron Mountain), Greg Markkanen (R-Hancock), John Damoose (R-Harbor Springs), and Sara Cambensy (D-Marquette), all representing the Upper Peninsula, issued a joint statement praising the Department of Natural Resources for renewing the metallic mineral lease for the mine.

They point to the 350 skilled trades jobs needed for the two-year construction of the mine, including iron workers, operators, electricians, carpenters, and painters. When the mine comes online, officials believe it will employ some 240 mining and business professionals.

In the past five years, Cambensy has championed mining in the U.P. She has successfully introduced numerous bills, passed into law, that she says will strengthen and expand mining in the U.P., protect the environment, and reward companies practicing safe mining techniques.

She says such legislation is especially timely with the national campaign to switch from fossil fuels to electric power. “You can’t be an advocate for climate change while opposing mining, because a green economy depends on digging up exponentially more minerals to make that transition,” she said in a recent radio station interview.

That argument doesn’t move Jean Stegeman, the City of Menominee’s mayor for more than 10 years. “Let me be as concise as possible: I am dead set against this mine. I know we need these metals for some of the things we use, but just because you found these resources it doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s a good idea,” she says. “And I know this can sound like a not-in-my-backyard thing, but the potential for disaster is frightening. When something bad happens people will look back and say, What where you all thinking?”

Stegeman says treating sulfide ore in the open tailings pit creates toxins like sulfuric acid, which can leach into the river and ground water tables.

“The Menominee River feeds into Green Bay, where the City of Menominee and the City of Marinette, across the river, have their drinking water intakes,” she says. “We draw surface water there. This is a disaster waiting to happen.”

Stegeman says she also stands with the Menominee Tribe and their objections to the mine. “These are people who have been there for hundreds of years and we should listen to their concerns,” she says.

While the mayor admits the eight-member Menominee City Council is split on their support of the mine, she says eight counties, including her own, have passed resolutions opposing the project. As for the 240 permanent jobs projected for the mine, she says those positions won’t go to local workers, but to outside mining specialists.

The most visible group opposing the Back Forty gold mine is the Coalition to SAVE the Menominee River Inc., a formidable grass roots movement co-founded in 2017 by Dale Burie and his wife, Lea Jane. They’ve built a force of support from Native American groups on both sides of the river, as well as environmental activists, residents, and concerned citizens from around the state and country alarmed by the possible pollution of the river.

Dale Burie grew up in the area and graduated from Stephenson High School before following his music calling to Nashville, Tenn., where he worked as a musician and promoter. Lea Jane, also a musician, sang backup for music stars including Elvis Presley, Dolly Parton, and Merle Haggard.

When the couple retired, they moved back to the U.P. and built their retirement home near the Menominee River. In addition to concerns for their riverfront property, they said they were especially moved by the deep reverence for the river displayed by the Menominee Tribe.

A partner in the coalition is Guy Reiter, a community organizer from the Menominee Tribe who serves as executive director of Menikanaehkem Inc., a nonprofit group of “community builders.” Reiter’s organization is based on a reservation in the Village of Keshena, north of Green Bay, where it supports sustainable projects in the region.

In the past five years the partnership has raised community awareness of the mine through media campaigns, parades, bridge walks over the river between Menominee and Marinette, and 5K walk-a-thon festivals, all the while raising money for legal fees to block the mine.

Those efforts, detailed on the coalition website, have drawn national attention as well as acclaim from around the world.

“There’s never been a successful sulfide ore mine that hasn’t contaminated the waters of its region or its chemistry,” Burie says. “This doesn’t happen in the mining action itself, but in the reaction to the cyanide used to leach out the minerals from the sulfide ore. This deposit runs parallel to the Menominee River.”

He acknowledges that mining is embedded in the history of the U.P. The location of the sulfide ore vein alongside the river is the dynamic that changes the equation, he says.

Burie says liquefaction of the chemicals in the tailings pit from exposure to the atmosphere eventually will find a weak point in the dam, allowing toxic material to escape into creeks and valleys, and eventually into the river.

Such a failure occurred in Brazil in 2019, when an iron ore tailings dam collapsed and the resulting mud slide killed more than 300 people at the mine site and beyond. That mining company was responsible for a similar disaster at another mine in 2015 that killed 19 people and devastated a river.

Burie says he isn’t convinced Gold Resources can rework the project to make the mine safe. “Although they’re saying they’re going to come back with a new and improved mine design, I haven’t seen that yet,” he says.

He acknowledges that the dry stack method proposed by GRC to handle tailings “is somewhat safer,” but because it’s more expensive, he’s skeptical about the company following through.

Last April, Burie and his wife, along with Al Gedicks, a prominent tailings mine critic and environmentalist from Wisconsin, met for two hours with Palmiere and Kim Perry, Gold Resources’ CFO.

Burie says that as Gedicks explained the Michigan state permitting process, Palmiere and Perry incorrectly believed that Aquila had obtained four of the five necessary permits to open the mine. “They said they were going to proceed with the Back Forty project and we told them we would definitely stand in opposition and we are prepared,” Burie says. “We have an environmental attorney staff that’s very good, and if it goes to court, we’re prepared to do so.”

Palmiere describes the meeting as informative, and says he agreed to further meetings and taking part in a public forum when the mine plans are formalized.

Another hurdle GRC may need to overcome is the possible reclassification of the Menominee River as a navigable waterway by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The Menominee Tribe is petitioning the Corps to update a 1979 designation and declare the entire Menominee River as a federal navigable waterway. That label, which already applies to the Wisconsin side of the river, would place the entire river basin under federal jurisdiction — making it subject to the Clean Water Act under the Environmental Protection Agency. It would also rescind Michigan’s sole authority over the mining permitting process.

The river is already deemed navigable from Green Bay two-and-a-half miles up the mouth of the river on the Wisconsin side to the Interstate Bridge, Burie says, facilitating traffic to and from the Marinette Marine Shipyard, where ocean-going war vessels are built.

The five-mile-long steel suspension bridge between the two states carries U.S.-41 over the river, connecting the cities of Marinette and Menominee.

A year-long public comment period on the petition ended July 20. Burie says the Coalition turned over to the Army Corps 253 letters it received supporting the petition.

Gedicks, an environmental sociologist, Indigenous rights activist, and author, is an emeritus professor of environmental sociology at the University of Wisconsin–La Crosse. He’s also the executive secretary of the Wisconsin Resources Protection Council, a statewide environmental organization that opposes metallic sulfide mining projects in the upper Midwest.

He says changing the designation of the river to navigable will have repercussions beyond giving the EPA jurisdiction over the mine project.

“If the EPA has a greater decision-making role in the project, that would mean that the Tribe, for the first time, would have the ability to argue under the National Historic Preservation Act that the excavation of the mine would endanger their traditional cultural resources,” Gedicks says. “That issue has never been on the agenda of Michigan because Michigan doesn’t abide by federal regulations as the sole permitting authority for the mine.”

Gedicks says after blowing $100 million with nothing to show for it, Aquila Resources was nearly bankrupt when it went looking for new investments in 2021. “They sent out their financials and background on the project to over 30 investors, and none of them took the opportunity to invest in the project,” he says.

He adds Aquila’s version of the events in its sales pitch was that the wetlands permit setbacks were due to technicalities, and a new permitting process will be relatively easy and inexpensive to pursue. “None of those assumptions are accurate,” Gedicks says. “So, this project is proceeding on the basis of a false narrative that isn’t reflective of the grass roots opposition to the project.”

Regardless of how GRC proceeds, the Back Forty Mine is still a sulfide ore operation that will have potentially grave consequences, Gedicks says. “The value of the ore body discounts the environmental effects of storing 50 million tons of mine waste on the surface,” he says. “It also doesn’t consider the environmental and economic cost of maintaining that structure in perpetuity.”

Palmiere cites his international experience as a bedrock underpinning the company’s operating philosophy that will eventually win over skeptics.

“Anywhere in the world, whether it’s in the United States, Canada, Mexico, or Africa, you cannot build a mine without obtaining what’s known as your social license,” he says, ironically mirroring Chairman Corn’s comment. “And what that means is listening to and working with the local community and the people who are directly impacted by the mine. It’s fundamental to any mine anywhere in the world, and the U.P. is the same.

“Can we make everyone happy all of the time? No. But what we can undertake is to listen to their concerns and, to the greatest extent possible, accommodate or address those concerns in the way we design the mine and the way in which we operate the mine.”

Northern Riches

Michigan’s Upper Peninsula powered the Industrial Revolution and today is a source of minerals needed to build lithium-ion batteries.

The first great mining boom in the country wasn’t the 19th century California gold rush; rather, it was a copper stampede in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula that was sparked by a report describing rich lodes of the mineral. The report was delivered in 1841 to the state Legislature by chief geologist Douglass Houghton.

In the following years, thousands of prospectors and explorers found their way to the U.P. and the Keweenaw Peninsula, along what is now known as the Copper Range on the Lake Superior shoreline, according to Michigan State University researchers.

Their discoveries — more than 5 million tons of copper were mined from 1845 to 1969, when the mines shut down — are credited with fueling the Industrial Revolution in the United States. Houghton’s most intriguing discovery, though, was his find of gold while on an expedition in the U.P. in 1845. Writing in Michigan Conservation Magazine in 1945, geologist Franklin G. Pardee relayed that Houghton left a copper camp with a Native American and later returned with specimens of rich gold ore.

Fearing his crew would desert their mining jobs to search for gold, Houghton kept the find a secret, revealing it only to his close friend, local prospector Samuel W. Hill, who’s said to have been immortalized in the euphemism: “What the Sam Hill.”

Tragically, a few days later, Houghton drowned at age 36 when his boat was swamped during a storm on Lake Superior. “He either did not make any notes of the location of this gold ore, or they were destroyed with him,” Pardee wrote in the magazine. It’s not known if Hill ever revealed the location.

In his short career, Houghton was a medical doctor, a professor at the University of Michigan, and a one-term mayor of his hometown, Detroit. The city of Houghton, Houghton Lake, Houghton County, and Douglass Houghton Falls near Calumet were named after him.

Since his time, mining no longer dominates the U.P. The largest industries today are real estate, manufacturing, and health care. The lure of gold, though, remains seductive, even as minerals such as nickel are becoming more valuable.

The Eagle Mine, which opened in 2014 in Marquette County, is America’s only nickel mine, and a critical national resource in the burgeoning lithium-ion battery industry that powers electric vehicles. The other active mine in Marquette County is the Tilden iron mine, which opened in 1989.

The U.P.’s longest running gold mine was the Ropes Mine, north of Ishpeming in Marquette County; it operated on and off from 1883 until 1991. Over its lifetime, the mine produced almost $1 billion worth of gold.

In 2023, a Canadian-based company is planning to open the new Highland Copper Mine in northern Gogebic County. The company also plans to revive the nearby White Pine copper and silver mine, which operated from 1955 until it closed in 1995. The 13 miles of underground operations produced 4 billion pounds of copper and 45 million ounces of silver.