It was 1969, another year with way too much on Barry Kramer’s plate. At 26, the Mumford High School graduate — who had sampled Wayne State University’s short-lived Monteith College open-curriculum experiment before deciding to skip ahead in life — was operating no fewer than five businesses that catered to Detroit’s simmering youth counterculture.

Inspired by a trip to England, where he experienced London’s Carnaby Street, the lean, mustachioed multitasker opened the Midwest’s first head shop and hippie bookstore in 1967: Cambridge Mixed Media, on Cass Avenue near Palmer St. One of his employees was a young Gilda Radner.

Kramer also owned Full Circle, a record outlet at Cass and Warren avenues frequented by Wayne State students, and co-owned a talent booking agency that managed rock bands, including Mitch Ryder’s post-Detroit Wheels outfit, called Detroit. Meanwhile, he was trying his hand as a concert promoter.

Now Kramer was on to something new, a venture begun by a clerk at Full Circle, a Britisher and former musician named Tony Reay.

The clerk had started a music newspaper and named it after his favorite band, Cream, although he used an alternate spelling. The funky broadsheet turned up in March 1969 in head shops, bookshops, record stores, and other establishments along the Cass Corridor, with prospects that were decidedly limited; it was one more underground rag in a raggedy new-media era.

Now, a half-century after its debut and 30 years since its demise, the mythos of Creem magazine is thriving — a Detroit urban legend that actually happened.

The reputation of the rude, bold, brilliant, cosmo-lysergic, witty-gritty, rock music monthly has risen — steadily, tectonically — and it now looms high in Detroit media history. A 50th anniversary film documentary debuted in spring 2019, along with a rush of old enthusiasm. Hope for a comeback springs eternal.

The attention has sparked an appreciation for what the Creem team pulled off, and what they presaged. Namely, a hip downtown startup before hip downtown startups were a thing in Detroit, or at least a thing anyone talked about. They practiced disruption at a time when disruption was a punishable offense, not a business model, and prototyped the under-doggedness of the pasta-makers, carpoolers, and crowd-science AI firms now fueling Detroit’s entrepreneurial rebirth. Think “Detroit Against Everybody” circa 1969, two years removed from the city’s race riots.

“Creem represented the whole idea of ‘Detroit Hustles Harder’ before that became a thing,” says J.J. Kramer, Barry’s son. “What they were able to accomplish in the media space, not being on the coast where a lot of the printers were located, was kind of amazing — a testament to their ingenuity, work ethic, and desire to do things on their own terms.”

A miraculous crew of misfit writers and editors mentored a generation of music fans nationwide. In Seattle, an adolescent Kurt Cobain — who, with his band Nirvana, kicked off the grunge scene in the early 1990s — said he learned everything he knew about punk rock from Creem, which bragged on the cover: “America’s Only Rock ’n’ Roll Magazine.”

The publication and its most iconic iconoclast, gonzo rock essayist, satirist, and cultural critc, Lester Bangs, were depicted 19 years ago in “Almost Famous,” director and former Creem contributor Cameron Crowe’s semiautobiographical movie about his rock journalism days, with the late Philip Seymour Hoffman cast as Bangs.

In spring 2019, the irreverent magazine received reverential treatment in “Boy Howdy: The Story of Creem Magazine,” a 73-minute documentary tribute.

In its heyday, a fanatical following consumed the trim tabloid as though it were an illegal substance. It was a dope sheet on Detroit’s robust musical scene: Motown Records, a trailblazing FM radio subculture, and scores of blow-the-doors-off regional rock bands. The Grande Ballroom, Eastown Theater, and other venues rocked nightly. The scene flashed with opportunity, and within the sinews of “sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll,” a new category of entrepreneur emerged: the cool head with a head for business.

“There were a lot of these guys around,” says Roberta Cruger, one of Kramer’s earliest business staff employees and the first admin at Creem. “(Promoter) Punch Andrews had the Hideout Club in Birmingham and managed Bob Seger. Pete Andrews was managing acts and was a concert promoter, and though John Sinclair was considered an activist, he was managing the MC5 and running the Blues and Jazz Festival in Ann Arbor. It was an era of people seeing music as a vital and vibrant business, so everybody had their fingers in it.”

In 1975, Kramer told The Detroit News: “I was a pre-med student at Wayne State … and was swept up in the swirl of the ’60s. We used to call ourselves hippies, and the focal point of our circle of friends was music.”

Kramer invested $1,200 and agreed to house Reay’s publication at Full Circle, although creative differences soon arose. Reay had a sober music journal in mind, and Kramer envisioned something grander. “Barry really wanted us to be Rolling Stone, and Tony Reay wasn’t going to bend,” says staffer Jaan Uhelszki.

Reay split and Kramer found new premises in a dilapidated building at 3729 Cass Ave.

During that time, underground papers were founded with manifestos, not business plans. Kramer described the venture as “naive, rude, adolescent, simple, and simplistic” in an early issue. But he had a strategy: attract young, extraordinarily clever rock ’n’ roll-obsessed writers willing to work for a trifle, and put them up at the office. It was an idea that fit the tenor of the times.

The talent arrived in droves.

Virtually every editor and writer present at Creem’s creation, or soon thereafter, became an industry icon, including Bangs, Dave Marsh, and Uhelszki, a business-savvy music obsessive from Lathrup Village who started as Creem’s “subscription kid” and became a star writer.

Seminal editor Marsh joined in the summer of 1969, after spending “about two minutes” at Wayne State. The Waterford Township native described himself as “a skinny 19-year-old suffering from overexposure to LSD and the MC5, with absolutely no prospects.”

Bangs, a Californian, began freelancing for Creem in 1970 after Rolling Stone founder Jann Wenner sacked him for disrespecting the band Canned Heat in a review. In 1971, Bangs moved to Michigan as a staffer and fell in love with the city’s temperament, calling Detroit “rock’s only hope.”

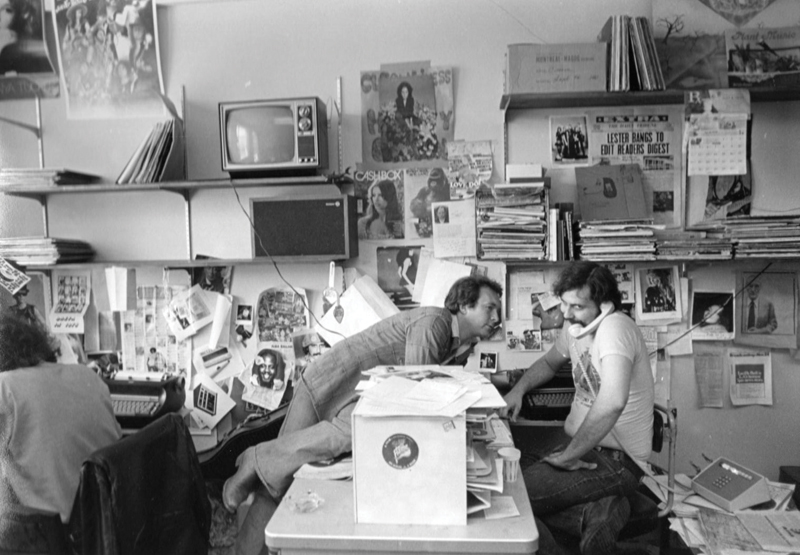

At 3729 Cass, a dingy, three-story, cast-iron pile, the editorial staff took up the ground floor, Mitch Ryder’s rehearsal studio was on the second floor, and Barry and Connie Kramer were perched on top. An attached clapboard house closeted most employees.

“There was a living area with sofas, and people were listening to records,” says Cruger, who eventually wrote for Creem. “It was an alternative workspace in the way corporate headquarters today are called campuses. But Creem was a hybrid because we were living together.

“It didn’t feel like a commune. We weren’t doing drugs. We were pretty much all work and no play. The work was the play; listening to music, typing away. A little ad hoc, a little like Salvation Army furnishings — but everyone was focused.”

Not that there wasn’t commotion; arguments raged over the loud music playing constantly. But there was a round-the-clock commitment to the mission, which was the music. Writers would emerge from the communal bathroom with a flush of inspiration and head straight back to their Smith Corona Galaxie Deluxes.

The writing — articles, essays, reviews, short takes, headlines, and captions — were, at times, profane, profound, hilarious, crude, confrontational, and almost infamous.

The “business department,” better known as Kramer’s office, where Cruger worked, was barely separated from the writers.

Creem was a circus and Kramer the ringmaster. “He curated this staff of people who were all a little bit off,” J.J. Kramer says. “He was creating this very distinct identity. Whether he thought about it as a brand, I don’t know. But the things he was curating were the core values of what a brand would stand for.”

Uhelszki says most Creem staffers came from dysfunctional families. “There was a common misfit-ness, and Barry was like the wizard to us,” she says. “He was a genius about people, but a little Machiavellian. He was a beautiful man, beautiful looking. Really elegant, with really good manners. And so verbally quick and always with the ability to know exactly what bugged you.”

In business, Kramer was agile under pressure and fast on his feet. “Certainly, there were very lean times,” Cruger says. “I was doing the bookkeeping and writing the checks, and I remember once telling Barry there was no money in the account. He just said, with a kind of smirk on his face, ‘You’ve got to spend money to make money.’ Somehow the money would magically appear.”

Circulation of the early issues was limited to the Detroit area. Creem’s first distributor shipped copies of the original large-format, folded newsprint version to porn shops, among other outlets, that were confused, it seemed, by the name.

Frustrated, in 1970 Kramer flew to Philadelphia and struck a deal with Curtis Circulation Co., a distributor with national reach. Curtis got the publication into retailers across America. It was a decisive turn for Creem, which by 1970 was a tabloid.

“That put us into grocery stores and pharmacies,” Cruger says. “We were selling magazines, even selling magazines internationally. I remember hearing that people in Europe were buying it and wondering how it even got over there.”

Kramer worked the angles. Susan Whitall, fresh out of Michigan State University with an English degree, had contributed reviews and stories in the early ’70s, and Kramer wanted to put her on staff.

“He had scoped out that there was a program where the state of Michigan would pay half the salary for six months if the person had been unemployed,” Whitall says. “He did that with me, so thank you, state of Michigan.”

At the same time, Kramer could be bare-knuckled. When Creem’s original printer blanched at expletives in an issue and blacked them out, Kramer fired the company and refused to pay the print bill.

While managing Mitch Ryder, he felt the group wasn’t getting enough radio play. J.J. Kramer relays the story he heard from his mom: “He went out to Los Angeles and barged into the A&R rep’s office, jumped up and stood on his desk, and refused to leave until the guy agreed to put more effort into promotion.

“It was all with this Detroit chip on his shoulder. I think that was his motivation. He was a bit behind the eight ball, and that created this motivation and this constant chess game trying to figure out what’s the next angle.”

By 1971, Creem was filling up with ads from stereo manufacturers, jeans outlets, guitar makers and, way in the back, small ads that hawked such products as lice-killing shampoo.

Full-page display ads for new albums mostly paid the freight.

“The record companies were making a lot of money and spending it,” Cruger says.

And Kramer could work that crowd. “He was a hippie and a businessman, and you couldn’t distinguish the two,” Whitall says. “He was both. When he was going off to a distributors’ convention or something he would say, ‘I’m putting on my white belt and my white shoes,’ and he was going to go talk their language and schmooze with those corny people — and not just talk their language, but dress like them.”

At its peak, in the mid-to-late ’70s, Creem’s 150,000 circulation was topped only by Rolling Stone among America’s rock magazines.

By that time, the Detroit tabloid had fled its Cass environs for a 120-acre farm in Walled Lake. Staff members were put up in a farmhouse, while Barry and Connie lived in a separate house on the property. There was a barn, horses, and alfalfa growing in the field. “It sounds bucolic, but it was kind of grungy,” Cruger recalls.

The office was a combination funhouse and intellectual hothouse. Kramer sometimes tangled with his editors, but never backslid on editorial integrity.

“He didn’t interfere,” says Whitall, who became Creem’s editor in 1978. “He never came in and said, ‘No, you’re not doing that story.’ But he was very hands-on when it came to the cover. He was determined to put everything that was in the magazine on the cover. I thought it was too garish, but we couldn’t talk him out of it.”

By late 1972, Creem had outgrown the farmhouse. The writers decamped to a house in Birmingham and the magazine followed in 1973, landing at 187 S. Woodward Ave. By 1976, most of the first wave of writers and editors were gone. Bangs, who left that year, died of a drug overdose in 1982.

Kramer found talented replacements, but record advertising had begun to slide in the early 1980s. It was a different era, and ultimately a tragic one for Creem.

Connie Kramer told a reporter that her husband “had demons, real demons.” He died of an overdose in January 1981 at 37, seven months after divorcing Connie.

From there, Connie became publisher, and in 1986 she sold the magazine to Los Angeles businessman Arnold Levitt, who moved it to California. Publication ceased in 1989.

Through licensing agreements, various attempts have been made to revive Creem. In 2017, a group led by J.J. Kramer acquired the brand his father built, and he developed the film project with director Scott Crawford.

Kramer was 4 years old when his father passed away. As an adult, he has tried to get inside his father’s head. “What I find interesting was how he created the environment that allowed the writers and editors to produce what they did. He was this eternal psychology student. He would study people and look for levers to pull.”

Could a Creem rise in Detroit today?

“Absolutely,” Whitall says. “But people have lost the ability to be funky and authentic. Literally, the phrase is ‘out of the trunk of his car,’ because Barry was selling Creem out of the trunk of his car. And people today want to have GoFundMe’s and cool offices downtown.”

Kramer, an intellectual property rights attorney with Abercrombie & Fitch, isn’t ready to revive the magazine, although he thinks the music industry could use a splash of Creem’s tenets.

“Creem was loved by both the bands and the fans because, at its core, it was about building a community around the music,” he says. “They had sort of a ‘kill your idols’ approach and didn’t suffer fools lightly. For all those record labels that took out ads in the magazine, it wasn’t pay-for-play. There could be a full-page ad for Journey, and the album could get trashed in a review. There was independence and integrity that’s missing today.

“In that golden era of the ’70s there was an incredible ecosystem of artists, writers, and fans, and they each held the other accountable. You don’t see that anymore and, because of that, the music has suffered.”