Researchers at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor have set a new efficiency record for color-neutral, transparent solar cells. The milestone brings them closer to having skyscrapers serve as power sources.

Many skyscrapers feature glass facades that have a coating to absorb and reflect light to reduce brightness and heating inside of the building. Rather than waste this energy, transparent solar panels could use it to limit a building’s electricity needs.

“Windows, which are on the face of every building, are an ideal location for organic solar cells because they offer something silicone can’t, which is a combination of very high efficiency and very high visible transparency,” says Stephen Forrest, the U-M Peter A. Franken Distinguished University Professor of Engineering and Paul G. Goebel Professor of Engineering, who led the research.

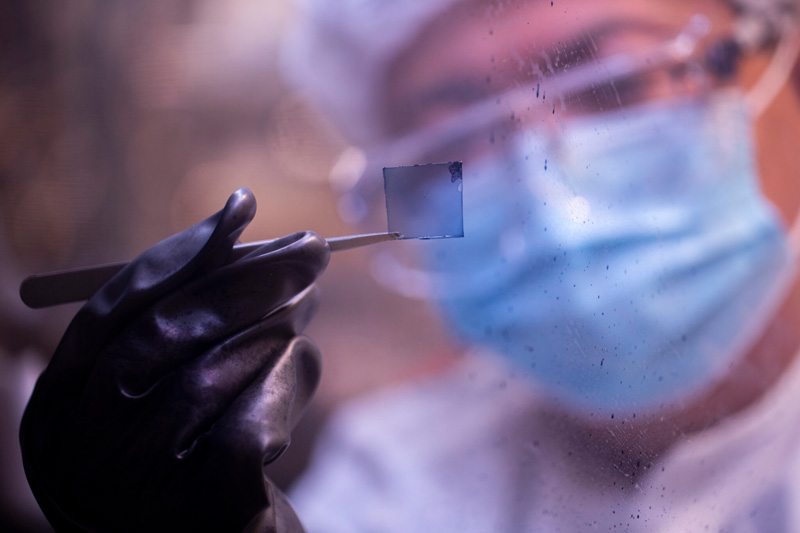

The U-M team achieved 8.1 percent efficiency and 43.3 percent transparency with their latest organic, carbon-based design. The new material features a slight green tint, which appears more like the gray of car windows, that boosts power generated from infrared light and transparency in the visible range. These two qualities are normally in competition with one another.

The first color-neutral version of the device was made with an indium tin oxide electrode. A silver electrode improved the efficiency of the solar cells to 10.8 percent and the transparency to 45.8 percent. However, that version’s slight green tint may not be acceptable in some window applications.

Regardless, both versions of the device use materials that are less toxic than other transparent solar cells and can be manufactured at a large scale. They also can be customized for local latitudes, which will take advantage of the fact that they are most efficient when the sun’s rays are hitting them at a perpendicular angle.

“The new material we developed and the structure of the device we built had to balance multiple trade-offs to provide good sunlight absorption, high voltage, high current, low resistance, and color-neutral transparency all at the same time,” says Yongxi Li, an assistant research scientist in electrical engineering and computer science.

Transparent solar cells are measured by their light utilization efficiency, which describes how much energy from the light hitting the window is available either as electricity or as transmitted light in the interior. Previous transparent solar cells have light utilization efficiencies of about 2-3 percent, but the indium tin oxide cell is rated at 3.5 percent, and the silver version has a light utilization efficiency of 5 percent.

Currently, Forrest and his team are working on several improvements to the technology, which can be placed between the panes of double-glazed windows, including reaching a light utilization efficiency of 7 percent, extending cell lifetime to about 10 years, and investigating the economics of installing transparent solar cell windows into new and existing buildings.

Researchers are from North Carolina State University, Soochow University in China, and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

The research is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The material is based on work supported by the U.S. Department of Energy Solar Energy Technologies Office as well as the Office of Naval Research and Universal Display Corp.