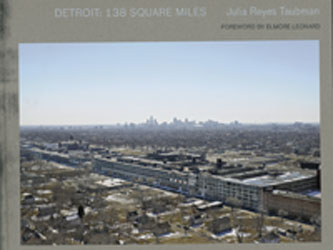

By land, air, and sea, Julia Reyes Taubman used her camera to document Detroit, from its glaring warts to its shining edifices. In 40,000 photos taken between 2005 and 2011, Reyes Taubman captured every nook and cranny of Motown — from motorcycle clubs to scattershot neighborhoods. She then selected 400 mostly iconic snapshots for her book, Detroit: 138 Square Miles (Amazon, $40.95).

Reyes Taubman grew up on the East Coast, but she came to Detroit in 1999 following her marriage to Bobby Taubman, chairman, president, and CEO of Taubman Centers Inc. in Bloomfield Hills.

Like any artist, Reyes Taubman’s curiosity got the better of her. She started her sojourn on the grounds of the Cranbrook Educational Community in Bloomfield Hills — a scholastic Versailles created by architect Eliel Saarinen. From there, Reyes Taubman turned her camera toward Detroit, and never looked back.

Through her images, Reyes Taubman doesn’t try to explain the rise and fall (and perhaps the rise again) of one of the nation’s great cities. Rather, she documents what it’s like to live in a town that bends metal for a living.

Many of the photos are breathtaking, and some require research. One scene of a fence encircling the James Scott Memorial Fountain on Belle Isle portends abandonment — but in reality, the monument was under repair at the time. There’s also a scene depicting a tidy, yet empty dock at the Detroit Yacht Club, taken during the offseason. The next photo shows the hulking shell of the former Detroit Boat Club. An outsider wouldn’t know the difference between what’s been abandoned and what images were captured under special circumstances unless they tackle the abbreviated photo guide.

Meanwhile, an opening essay by Jerry Herron, dean of the Irvin D. Reid Honors College at Wayne State University in Detroit, theorizes that many Detroiters left for the suburbs because they had the wheels and the pocketbook to afford a new home. Yes, the American economy took off in 1950, but the dream of living in suburban solace was fueled by poor urban planning that gripped Detroit as far back as the 1860s, when the city was the stove capital of the world.

Let’s face it: Few people want to live near a factory. But that’s what Detroit offered. When the automakers gained prominence, the industry ignored sound urban planning and, by the early 1930s, they were gearing up for World War II. By 1945, the city had spent every last drop of its resources to defeat Germany, Japan, and Italy.

It took five years to get the nation’s economy humming again, and even as Detroit produced more than 80 percent of all the cars and trucks in the world, it couldn’t fill all of the factories left over from the war. As time passed, the decentralization of production and foreign competition crushed the city.

The Greatest Generation won World War II and accelerated the spread of democracy to nearly every corner of the world, but those men and women neglected to take care of their homeland. Detroit still stands defiantly as the one of the great brain trusts, but our grandparents neglected to clean up the engine that propelled them to greatness. Reyes Taubman captures the aftermath. db

bR.J. King

brjking@dbusiness.com