While working on a book three years ago, Rob Keil came from California to pay a call on Jim Secreto, the collector who, as Keil puts it, keeps “the story of car advertising all in one big room.”

Secreto stores this trove at a secret Oakland County location — 1,400 square feet filled floor-to-ceiling with rare illustrations, dye-transfer photographic prints, 8 x 10-inch color transparencies, car catalogs, and ad proofs.

It’s the accumulation of more than three decades of collecting. Keil was keen to see and photograph several works by the Mid-century illustration team known as Fitz & Van, who labored together for 24 years and refined their art to an exceptional degree.

Going behind the curtain, so to speak, Keil found the mass of material to be “fairly well organized” and Secreto’s passion to be palpable. “He’s just got an incredible library of stuff that he’s collected over many years,” Keil says by phone from San Francisco, where he’s an art director at Gauger and Associates, a marketing communications agency with offices near the Embarcadero district. “He can trace the evolution of Detroit advertising — car advertising, specifically — for about the last 100 years. He knows more about it than anyone else I know.”

As a 10-year-old looking at ads for General Motors’ Pontiac Division in his father’s old National Geographic magazines, Keil was mesmerized by the work of Fitz & Van. He saw their AF/VK signature, but it took him years to figure out the letters stood for Art Fitzpatrick and Van Kaufman. Working in gouache, the opaque form of watercolors, Fitz gave the cars mirror-like surfaces and dimensional distortions to emphasize length, or — in the Wide-Track Pontiac campaign — width.

In gouache or colored pencil, Van supplied the detailed backgrounds, depicting aspirational locations and catching people in exuberant moments. “Glamor and storytelling,” Keil says. “I don’t know that anyone else did it better.” His definitive book, “Art Fitzpatrick & Van Kaufman: Masters of the Art of Automobile Advertising,” was published in August 2021.

In gouache or colored pencil, Van supplied the detailed backgrounds, depicting aspirational locations and catching people in exuberant moments. “Glamor and storytelling,” Keil says. “I don’t know that anyone else did it better.” His definitive book, “Art Fitzpatrick & Van Kaufman: Masters of the Art of Automobile Advertising,” was published in August 2021.

Secreto, who is 77 and lives in Oakland County, keeps going to work daily to attend to his collection, putting in sessions of at least four hours. During COVID-19, he made better inroads in organization. “I’d pull out a drawer and I’d go, ‘Man, look at this! This car line doesn’t even exist.’ ”

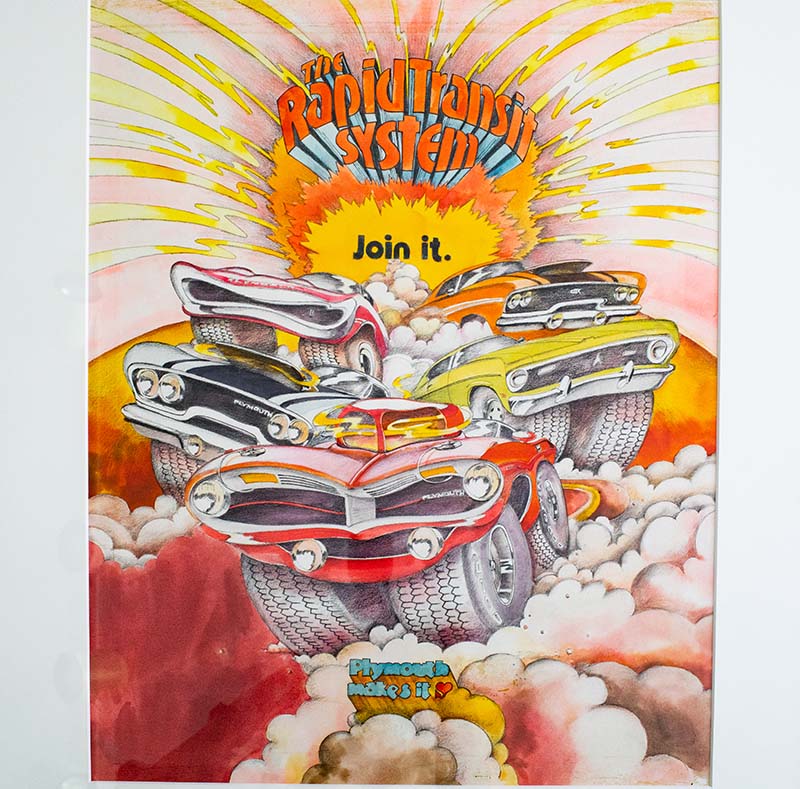

Along with plenty of material on behalf of survivor brands, he’s keeping the flame for the dearly departed such as Plymouth and the playful “Rapid Transit System” campaign of 1968 to 1972, as well as Oldsmobile and its Dr. Oldsmobile muscle car series of 1969.

Fielding the question of how he came to possess all of it, Secreto has a chuckle, saying, “The reason I’m laughing — I don’t want to brag — I am a real collector, OK?” In the 1970s and 1980s, on the way to becoming a top advertising photographer for automotive clients, he assembled what he rates as the largest North American collection of circus sideshow banners, which he keeps to this day. With three co-authors, he published “Freaks, Geeks & Strange Girls: Sideshow Banners of the Great American Midway” in 1996.

“It’s a cult book now,” he says. “They stopped publishing it, but it went into three printings. And I had four museum shows. I think collecting automotive stuff is just a natural path.”

Autos and freaks may not blend in every mind, but following the new path became inevitable after 1988, when Secreto started to share some creative space with Walter Farnyk in an old, repurposed church building at Maple and Livernois roads in Troy. Farnyk had been Secreto’s teacher at the Detroit Society of Arts and Crafts, which later became the College for Creative Studies. He died in 1992, and Secreto inherited the files for his mentor’s unpublished book on advertising. Closing up their shared space, he took everything to his main operation, which he describes as “a typical Detroit car studio.”

“I was hooked,” he says. “I was fascinated by the illustrations from the 1930s. It was the style of the art — the real decorative period for illustration.” After this beginning, he found himself being favored by “the old guard,” who would drop in for coffee, tell their tales of the ad business in the postwar era, and sometimes favor him with an item that was too good to toss out.

Then the tide turned against film photography and in favor of digital imagery. “In the mid-1990s, all the big labs were closing. I would go to the auctions, or they’d say, ‘Jim, you could come by, here’s the dye transfers.’ ”

He started collecting these handmade prints, usually in a 20-inch by 24-inch format. They were used by an art director and a retoucher to make corrections to the vehicle, the lighting, and the imperfections of the locations and landscapes. “It cost anywhere between $400 and $600 back in the 1960s,” Secreto says. “It’s a process that no longer exists.”

He started collecting these handmade prints, usually in a 20-inch by 24-inch format. They were used by an art director and a retoucher to make corrections to the vehicle, the lighting, and the imperfections of the locations and landscapes. “It cost anywhere between $400 and $600 back in the 1960s,” Secreto says. “It’s a process that no longer exists.”

Not quite realizing the golden era was ending, Secreto retired and closed his studio after a successful career. The collection he has amassed since then at his current hideaway location documents not only the themes and trends of advertising, but also the industry-wide standard of technical and artistic excellence. “You had to be creative, professional, within budget, disciplined — all of those things were demanded of you to be at this level in Detroit,” Secreto recalls.

With agencies always working in the service of the client, few individuals emerged as household names. Fitz & Van lived in Connecticut; their early successes were on campaigns for GM’s Buick Division and Ford Motor Co.’s mid-priced Mercury Division. After Semon “Bunkie” Knudsen became general manager of the Pontiac Division in 1956, he first showed his acumen by hiring Elliot “Pete” Estes and John DeLorean to handle engineering, and then showed his discriminating taste by lining up Fitz & Van for a long run on Pontiac’s behalf.

“They had a personal relationship with Bunkie Knudsen,” Secreto says. “They had what Detroit would call the Golden Touch. The agency (MacManus, John & Adams) couldn’t criticize their work because they were selected by GM management.”

It was incumbent upon MacManus art director Mickey McGuire to work with whatever Fitz & Van produced. Secreto remembers McGuire as “beloved — a gentle giant” at just over 7 feet tall. McGuire served as a stabilizing force between the artists and the agency. “He was the only art director they worked with.”

The MacManus agency started in Toledo in 1911 and, four years later, Theodore MacManus wrote copy for Cadillac’s momentous “Penalty of Leadership” ad, which responded to barbs from competitor Packard Motor Car Co. “In every field of human endeavor, he that is first must perpetually live in the white light of publicity,” MacManus proclaimed. Three decades later, ad execs named it the greatest advertisement to date.

The MacManus agency started in Toledo in 1911 and, four years later, Theodore MacManus wrote copy for Cadillac’s momentous “Penalty of Leadership” ad, which responded to barbs from competitor Packard Motor Car Co. “In every field of human endeavor, he that is first must perpetually live in the white light of publicity,” MacManus proclaimed. Three decades later, ad execs named it the greatest advertisement to date.

MacManus influenced Ray Rubicam, a writer at N.W. Ayer Co. in Philadelphia, who penned “Instrument of the Immortals” for Steinway & Sons. Rubicam poached account executive John Orr Young from Ayer, and they formed Young & Rubicam in New York, there setting the template for an agency of freewheeling creatives. In an odd twist of fate, Packard became a client.

Meanwhile, in Detroit, MacManus raided Campbell Ewald in 1933 to ensure a vigorous future for his agency. New partners were Waldemar Arthur Paul John, a University of Michigan alumnus who went by his initials, W.A.P., and James Adams, known for saying, “If advertising had a little more respect for the public, the public would have a lot more respect for advertising.” The MacManus, John & Adams agency, as it was known, came to have many departments and employ hundreds of people.

Meanwhile, in Detroit, MacManus raided Campbell Ewald in 1933 to ensure a vigorous future for his agency. New partners were Waldemar Arthur Paul John, a University of Michigan alumnus who went by his initials, W.A.P., and James Adams, known for saying, “If advertising had a little more respect for the public, the public would have a lot more respect for advertising.” The MacManus, John & Adams agency, as it was known, came to have many departments and employ hundreds of people.

Before World War II, it was hard to match Cadillac and Lincoln in quality of advertising. Chrysler pursued a course of “dynamic impressionism” that incorporated speed streaks and graphic exuberance. Plymouth soberly pitched value on congested pages that had a plethora of typefaces and a proliferation of inset boxes.

After the war, Studebaker was the first automaker to market all-new cars, and its ads were designed by Raymond Loewy & Associates. One ad said, “All over America the word for style is Studebaker.” Touting value and durability, Rambler, which produced a compact car, showed a mother and a toddler breezing along on the comforting thought that the next chassis lubrication wouldn’t be required until the kiddo was in kindergarten.

Chevrolet blossomed when Campbell Ewald produced lively pages for the all-new 1955 model: “For sheer driving pleasure, Chevrolet’s stealing the thunder from the high-priced cars.” The illustration was smart, the composition was simple and uncluttered, and the copy was fun to read while conveying a few key features.

Tasked with promoting Ford’s medium-priced Edsel brand in 1958, Foote, Cone & Belding (popularly known as Foote, Corn & Bunion) produced a tepid campaign with a big claim for pushbutton shifting by “Teletouch Drive.” The car line bombed.

By the time Chevy introduced the 1976 Monte Carlo, simplicity ruled the day. A stunning composition presented just a full-page black field and the shimmering automobile. Twenty words of copy plugging good taste and affordability were reversed, in white type, just above the bow-tie logo.

During more than three decades working on Ford’s marketing and then on the agency side at J. Walter Thompson and Team Detroit, Catherine Cuckovich saw sweeping structural changes as the ad business matured. These changes especially corresponded to the auto industry’s 21st-century financial upheavals. In 2010, Chevrolet dismissed Campbell Ewald after 91 years, which Cuckovich says “sent shock waves through the industry.”

Eight years later, Ford put its account up for review and sent the creative business to BBDO. There were cultural changes, too, as the “Mad Men” lifestyle of drinking and smoking gave way to more decorous behavior. And reductions in administrative support meant that everybody typed their own emails and logged their own appointments. “Most people now eat at their desk,” she says. “People go to the gym after work.”

Eight years later, Ford put its account up for review and sent the creative business to BBDO. There were cultural changes, too, as the “Mad Men” lifestyle of drinking and smoking gave way to more decorous behavior. And reductions in administrative support meant that everybody typed their own emails and logged their own appointments. “Most people now eat at their desk,” she says. “People go to the gym after work.”

Today, Cuckovich is an assistant professor at the Mike Ilitch School of Business at Wayne State University in Detroit. In her advertising strategy classes, she shows students some vintage pieces, introducing them by talking about the integration of imagery and copy. “The old ads look really boring compared to the new ones because these students are used to movement, color, and less words,” she says. “They’re not inclined to read as much. But we talk about the importance of the headline and the roles of different types of copy.”

Focusing her attention on some Fitz & Van pieces, she finds herself saying, “Oh, my gosh, it took forever. There’s just not the time or patience anymore for that.”

Secreto points out how, in the glory days, the cars had to be pre-photographed to give the illustrators a basis for their work. Photography for print had long been seen as a quicker, cheaper, and more accurate medium for ads.

In “American Automobile Advertising, 1930-1980: An Illustrated History,” the British writer, Heon Stevenson, states, “It has been claimed that the inception of color photography in automobile advertising from around 1932 removed the interpretative artistic middleman who had hitherto stood between the reader and the product; but, in reality, the artist, including the ‘deceitful’ elongator, continued to work alongside the photographer until after 1970.”

Secreto cherishes the best of that period and continues to dab away at the labeling and cataloging in his collection. He selects a dye transfer and then matches it to an ad or a catalog. “That’s what I’ve been doing the last year and a half; going on eBay and looking, for example, for an ‘Oldsmobile 1968 full-line catalog.’ Then I buy the catalog and attach it to the dye transfers that I have.”

He hosts astonished visitors, who stay an average of four and a half hours, leaving him spent. “I have to be more selective because it takes up so much of my time,” he explains. “It’s a day to prepare, it’s a day for the visit, and then it’s a day to put away. So that’s three days out of my week.”

As he readies the collection to move on, he finds himself walking through it with representatives of institutions and automotive corporations. They’re interested, but primarily in the departments that concern themselves. “I’m reluctant to break it up,” he says, as it would be another kind of penalty to see it auctioned off lot by lot.

In the meantime, he will go on opening drawers in the collection and surprising himself with forgotten treasures.