Once upon a time, Detroiters shopped downtown for new clothes at Hudson’s or Winkelman’s, picked out spring flowers and Christmas trees at Frank’s, and garnered their dinner ingredients at Chatham or Great Scott.

We smiled when Ollie Fretter offered us five pounds of coffee if he couldn’t beat our best deal, and then headed to his stores for a new stereo system — and then on to Harmony House for the records it played. We put up our feet — clad in Sibley’s shoes, perhaps — on a Joshua Doore coffee table and hoisted a bottle of Stroh’s or Towne Club cola.

Maybe it wasn’t quite like that, but the 20th century was indeed a golden era for homegrown merchants in metro Detroit. From dime-store debuts to Dittrich Furs, family-run shops took root downtown, supplying first the necessities, then the frills, for an upwardly mobile consumer base fueled by the wild success of the automobile. Unprecedented working-class affluence spawned dozens of retail chains that became household names and, in some cases, pop-culture icons whose low-budget TV ads still get played on YouTube.

As the new millennium approached, shifting demographics and the invasion of the big-box “category killers” doomed many old familiar logos. A handful — like Art Van and ABC Warehouse — not only survive, but thrive today, and industry observers say a new generation of innovators is bringing the personal touch back to southeast Michigan retailing.

“The sense of being that hometown-trusted merchant goes back to the trading post and the old general store,” says Shawn Kahle, who’s been a retail-marketing and PR executive in metro Detroit for a quarter of a century. “Retailing is about price, connection, and service. Service only matters if you make that connection first.”

Glory Days

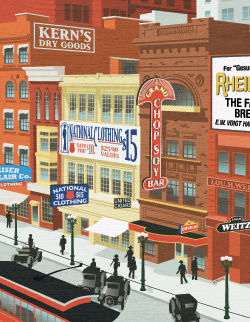

Merchants first began connecting with patrons at the core of downtown Detroit, when eponymous marquees like Vernor’s, Sanders, Kresge, and Kern’s were a stone’s throw from Campus Martius at the base of Woodward Avenue. Nearby neighbors eventually included Himelhoch’s, Harry Suffrin (which later merged with Hughes & Hatcher), and J.L. Hudson’s flagship store.

And it was, for all intents and purposes, the experimental laboratory for the malls to come. Within roughly the same space as today’s mega centers, shoppers had a world of options, from perching on a stool at one of two downtown Sanders ice-cream parlors, getting fitted for a suit at Capper & Capper, or looking for an engagement ring at Wright-Kay Jewelers.

Given the fortunes and density of the city at the turn of the last century, merchants like Sebastian Kresge were able to flourish. “The Kresge legacy is really the foundation for retailing in metro Detroit,” says Kahle, who directed corporate communications for Kresge descendant Kmart Corp. in the 1990s. “He made a conscious decision to locate in Detroit — the very first five-and-dime store was across the street from where Compuware is now.”

S.S. Kresge dominated and, like others, found that the concepts developed in downtown Detroit translated elsewhere, too. By 1912, his chain had grown to 85 stores and, by 1918, it was listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Other retailers burgeoned, as well.

“Detroit was like the Silicon Valley for retailers,” says Fred Marx, a longtime merchant and PR executive. “Every category was represented. And there’s a reason that we were the birthplace for a lot of specialty stores.”

Marx — who came to metro Detroit in the 1970s as a vice president for Hudson’s — posits that the lack of a major secondary department-store chain left a void to be filled by niche merchants and boutiques.

Other cities had a dominant retailer, occupying the berth Hudson’s did in Detroit — but generally also supported two or three competing department stores. Not so here. Jacobson’s posh emporiums were based in Jackson and mostly located outstate. Crowley, Milner & Co. was an upscale operation poised to give Hudson’s a run for its money but for the untimely death of co-founder William L. Milner in 1923. Milner’s heirs sold the family stake to outside investors and, while Crowley’s flourished through most of the century, it never became a Hudson’s-style powerhouse.

The Shift to Suburbia

Among the first chains to grow were grocery stores, which, through the 1930s, evolved from corner shops to family-run coalitions of a dozen stores or more, says Ted Simon, a former executive with Allied Supermarkets, one-time parent company of chains like Packer, Chatham, Great Scott, and Farmer Jack.

Post-World War II prosperity fueled more expansion as an increasingly consumption-oriented society headed for the suburbs. “And, of course,” Simon says, “retailers followed this growth.”

Moving outside the city’s core meant that merchants — accustomed to a captive audience dependent on stores on the streetcar line or within walking distance — had to become real-estate experts as well as retail titans. Some stumbled; others capitalized on a knack for selecting and financing new locations.

By the early 1960s, suburban retail expansion was in full swing, the discount era ushered in by a new Kresge concept — Kmart — on Ford Road in Garden City. A young pharmacist named Eugene Applebaum opened the first of many drugstores at the corner of Michigan and Greenfield in Dearborn. Hudson’s was refining the mall-anchor concept it pioneered at Northland Center in 1954, and Winkelman’s satellite branches were radiating out from Gratiot, Grand River, and Michigan avenues into suburbs such as Grosse Pointe and Lincoln Park. Many other well-known names followed suit.

When it opened in Detroit in 1928, Winkelman’s was synonymous with style and fashion.

The merchants used rudimentary technology to assess store performance and plan new ones. Margaret “Peggy” Winkelman recalls the room-size, climate-controlled business computer her late husband, Stanley Winkelman, acquired while running the chain. The retailer peaked at 168 locations in 1978, including a branch in Chicago’s vaunted Water Tower Place mall.

“He knew everything in every store that had sold itself the day before,” says Peggy, noting that her husband and other executives would make frequent store visits to ensure that uniform standards were upheld.

Another old-line trick of the trade was the standardized, elaborate showcase displays, which were changed weekly. “We had marvelous window designers,” Peggy says, “and all the windows were exactly the same from store to store. So if a woman saw something driving by, she could go to her nearest [Winkelman’s] and be sure of finding it.”

In that era, Mr. and Mrs. Winkelman and the store staff would travel to Europe for haute-couture shows, gathering ideas and bringing them back to be adapted for Midwestern consumption. Winkelman was picky about quality, reviewing the minutest detail of tailoring, workmanship, and fabric. He’d also insist on escorting younger fashion buyers to the Louvre in Paris.

“He told them, ‘You’ll appreciate fashion and clothes — and look at this all with a much sharper eye — if you first look at the great works in this museum,’” Peggy says. “He really did look upon fashion as an art form.”

Around the same time, another enterprising young merchant was using real-estate savvy and store standardization to his advantage. Eugene Applebaum, who founded Dearborn’s Civic Drugs in 1963, soon hired others to take his place behind the pharmacy counter and embarked on an expansion drive that would continue until he sold his chain to CVS Corp. in 1998.

Before computers were generally available, the drug-store proprietor analyzed the ZIP codes on each prescription to see where business was strong and likely to support more stores. He also standardized prices and store layouts, eschewing the hodgepodge approach then in vogue elsewhere. Eventually, the community drugstores were all rebranded under the Arbor Drugs name — in part because the Ann Arbor store had newer and expensive signage that otherwise would have to be scrapped.

“People who worked at Arbor basically used rulers to keep the shelves orderly,” Marx says. “They never closed a store under him. He had a perfect record in picking locations.”

Unlike some of his contemporaries, Applebaum never starred in his own advertising, instead employing veteran TV father figure William Schallert for many an Arbor spot. “And only for pharmacy,” Marx points out, “which reinforced the notion that this was a first-class professional health-care environment. Gene Applebaum didn’t want to compete over the price of a bag of potato chips.”

Executive Guarantee

Price competition was a reality, though, and through the 1970s and 1980s, many retail chiefs took to the airwaves to prove that no one else could beat their best deal. After half a century in the ad business, Fred Yaffe still speaks fondly of the slogan his firm developed for ABC Warehouse: “The closest thing to wholesale.”

Later, ABC chief Gordon “Gordy” Hartunian would appear in a series of clever commercials, following in the footsteps of Ollie Fretter, New York Carpet World’s Irving Nusbaum, D.O.C. Optics Corp. founder Richard Golden, and various local car dealers.

When a merchant puts his own persona on the line, Yaffe says, “it gives one message to the marketplace: ‘I’m not going to screw you.’ For consumers, that’s a comforting feeling.”

Kahle agrees. “We know the consumer decided years ago that purchases ultimately would be determined by price,” she says. “As more and more specialists entered the market, it caused regional and local retailers to say ‘How can I differentiate myself?’ Not on price or product — it had to be on service or reputation.”

Competition and Changing Consumers

The kitschy, goofy, low-budget ads mostly waned when serious national competition started moving in on local retailers’ once-captive home market.

“Starting in 1985, Detroit was deluged with new power centers, big-box retailers, you name it,” says Barry M. Klein, a West Bloomfield-based retail developer. “Over the next five years, it really caught up with us. Not everyone wound up staying in business.”

Frank’s Nursery & Crafts, whose Detroit roots date back to a 1942 grocery store, is a case study in the big-box squeeze. After gravitating to the more profitable — but seasonal — nursery business throughout the ’40s, Frank’s operators eventually expanded the chain — usually by snapping up small regional lawn and garden centers — to 80 locations by 1980. Craft supplies had been added into the merchandise mix and, in 1983, Frank’s was sold to the publicly traded conglomerate General Host Corp. They continued to expand the chain and add new concepts — such as temporary Christmas outlets — while doing little to shore up the aging core of indoor/outdoor garden centers.

Next thing you know, says PR veteran Chris Morrisroe, “You had Home Depot and Lowe’s coming in every two minutes.” And their big, fresh warehouse stores were in sharp contrast to the smaller, older, fertilizer-filled Frank’s branches.

Morrisroe, principal of Chris Morrisroe Communications in Waterford Township and a former PR director for Frank’s, could see the writing on the wall. “Michaels came in and they cornered the craft market,” he says. “A couple of bad seasons and you’re done.”

Frank’s management made several attempts to find a niche for the venerable chain, including a more upscale Pier One-style concept, before finally conceding defeat and liquidating some 170 stores in 2004.

Industry analysts point out that many once-thriving retailers are defunct thanks to bad timing, unavoidable shifts in consumer tastes, and other external factors, rather than failed management. In Frank’s case, it was the store format, and that’s true of some bygone supermarkets too, Simon says.

For example, consumer preference for more takeout and ready-to-eat foods became an obstacle for older markets that couldn’t retrofit to provide salad bars, sushi stations, broiled chicken-to-go, and other fast food options, he says. Then, too, an explosion in selection within individual product categories — low-sodium, high-fiber, low-fat, heart-smart, eco-friendly, and fragrance-free versions of seemingly everything — meant that more and smarter shelf space was needed for even an average array of goods.

“The whole configuration may be the best in its area, but all of a sudden you’re outflanked,” Simon says. “Think about cereal alone, or yogurt. It’s a continually changing business model. But as a grocer, you have a brick-and-mortar commitment. That makes change difficult.”

Retailing, according to Simon, is just like any other industry, but with shorter cycles. Aside from new national competition and the impetus for capital-intensive growth, other forces preyed on local retail chains. Among them: lack of a logical successor. A number of local chains died out when outside investors were brought in, or when second-generation operators had to sell because no heirs came forward to take their places.

“So many of these companies started with one person and one idea,” Morrisroe says. “Then the marketplace becomes more global. Families step aside — orget pushed aside.”

The Next Generation

“Retailing is hard work,” Kahle says. “If you’re a shop owner of one store or 3,500, it’s really a 24-hour enterprise. If a store opens at 9 a.m., people are there at 5 a.m. to get it ready. When the rest of the world is off work, you’re busy. For younger generations, there are so many other options and educational access and mobility.”

Gary Van Elslander, who succeeded his father, Art, as president of the Art Van furniture store chain in 1983, agrees. “You might have an owner who was very involved,” Van Elslander says. “But if there wasn’t some conscious plan to bring in new blood or family, the business is gone when the owner dies or retires.”

Under Greg’s watch, the company has weathered such changes as the shift to Asian suppliers and the introduction of Web-based customer service.

Currently, Art Van is adjusting to the credit crunch that’s fettered its famous zero-percent financing deals and is rescaling furniture to meet the downsizing needs of an aging clientele, while still working hard to attract the next generation of buyers.

Another local chain not lacking a scion is Hiller’s, the seven-store upscale grocery chain that dates back to a 1940s Detroit market. Current CEO Jim Hiller, the founder’s son, recently announced that his own son, Justin, had joined the company as vice president.

Meanwhile, Jim Hiller is grappling with Michigan’s economy head-on. “We’re [in] a period when the big-box store is in favor,” he says. “Many of those small companies that catered to service and quality are gone because people don’t care anymore. Retailing is like the moon — it shines only by reflected light.”

After receiving publicity for a recent op-ed piece about buying American automobiles, Hiller really found his voice. “I had an epiphany,” he says. “Nobody’s coming to save us; we have to save ourselves.” Hiller has since taken to mentoring grass-roots food suppliers and has received thousands of e-mails from consumers about his “Buy Michigan” campaign. “I feel a renewed enthusiasm on the part of these people — that we do have salvation within our grasp,” he says.

Like most everyone else, Hiller has his nostalgic tales of shopping at Detroit’s landmark retailers. But he says he’s also having fun seeking out the next generation of homegrown merchants and entrepreneurs.

“There’s a whole new generation here,” he says. “Maybe they aren’t the same names and maybe you have to look for them, but they’re there.”