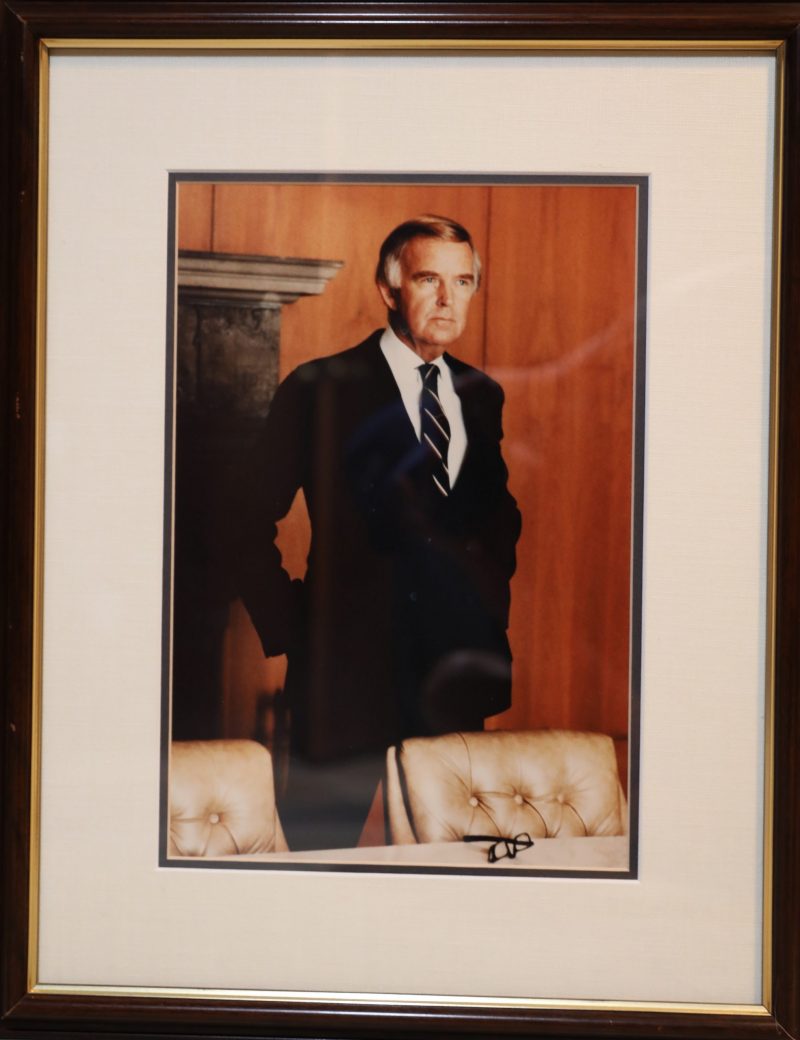

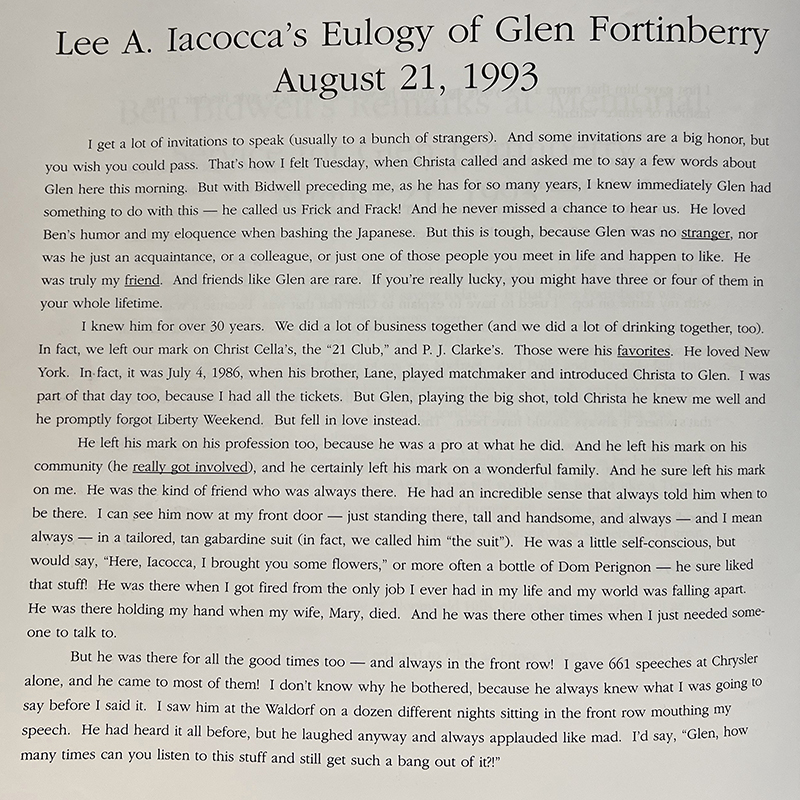

Lee Iacocca stood before mourners at Kirk in the Hills in Bloomfield Township on Aug. 21, 1993, and recognized plenty of familiar faces. Composing himself against tears, he invoked the memory of a man they all loved.

In life, Glen Fortinberry’s face was indelible, with a broad forehead under a swirl of reddish hair, a fine nose between penetrating eyes, and a determined mouth. Fortinberry had been chairman and CEO of Ross Roy Communications until his death four days earlier, after a year-long scrap with leukemia. Obituaries appeared in newspapers ranging from The New York Times to the Lawrence County Press in Monticello, Miss. — Fortinberry’s hometown and final resting place.

“I can see him now at my front door — just standing there, tall and handsome, and always — and I mean always — in a tailored, tan gabardine suit,” Iacocca said. (Fortinberry was 6 feet 4 inches.) “In fact, we called him The Suit.”

Even as one of Lido’s best friends, Fortinberry would exhibit a little self-consciousness before saying, “Here, Iacocca, I brought you some flowers.” Or it would be a bottle of Champagne. “He was there when I got fired from the only job I ever had in my life and my world was falling apart,” Iacocca said, remembering his dismissal from Ford Motor Co. after differences with Henry Ford II. “He was there holding my hand when my wife, Mary, died.”

Fortinberry came from the account side of the ad business; he called himself a “huckster.” Instead of building a reputation as the originator of a great slogan or campaign, his accomplishments had more to do with growing the agencies. As vice chairman of J. Walter Thompson, Ford’s agency at the time, he orchestrated the move of 250 employees from offices in the Buhl Building to new accommodations in Dearborn. Fortinberry led Ross Roy into providing integrated marketing services, transforming it into a one-stop shop offering merchandising, advertising, media buying, and even public relations services. But his biggest accomplishment may have been the push to get Iacocca into the national spotlight.

In the early 1980s, The Suit encouraged the Chrysler Corp. chairman to step into the role of auto industry spokesman. “I also encouraged you to speak out on national issues as well as industry issues,” he wrote in a letter to Iacocca on Sept. 15, 1986. “You’ve done that in spades and it’s obviously just one of the reasons you’re now perceived as a national figure.”

Fortinberry rose to the top in an era when an agency chief stood shoulder-to-shoulder with titans of industry. He shared a locker at Bloomfield Hills Country Club in Bloomfield Hills with another Chrysler exec, Bennet Bidwell, and he called Bidwell and Iacocca “Frick and Frack” after the Swiss comedy duo from the Ice Follies.

Besides the social prominence, Fortinberry and his family were in position to enjoy the spoils. Fortinberry’s son, Chuck, who was 29 years old in 1985, had the prescience to acquire a sleepy Chrysler-Plymouth-AMC-Jeep-Renault dealership in Clarkston. “It was in a sales locality that was 82 percent General Motors’ new-car registrations,” Chuck Fortinberry says. The next year, Chrysler broke ground for its new technical center 15 miles away, in Auburn Hills.

Ross Roy Inc. had started with a contrarian push against the trend of selling speed, freedom, sex, and prestige. Instead of poetic flair and hyperbole, Ross Roy relied on product knowledge. He may have been influenced by the precepts of Frederick Winslow Taylor, the efficiency expert who published “The Principles of Scientific Management” in 1911.

Roy’s formula worked in Janesville, Wis., where he succeeded in selling Dodge Brothers products. He came to Detroit, established his agency in 1926, and two years later, as Chrysler acquired Dodge Brothers in a $170-million deal, the feature-by-feature methods of comparing products spread to that brand, and subsequently to the new Plymouth and DeSoto divisions.

With so much to write about, Ross Roy Inc. set up at 2751 E. Jefferson (at Jos. Campau) in a building with an exterior distinguished by Corrado Parducci sculptures. Besides sales training and merchandising materials such as catalogs and brochures, the agency produced educational and training films. In 1940, it became a full-service shop, picking up the Dodge Truck account for a campaign touting the Job-Rated theme. The tag line proclaimed, “Dodge job-rated trucks fit the job! Last longer!”

An Ad Age profile of Ross Roy Inc. counted a staff of 82 employees when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. Chrysler became involved in producing for the World War II effort, which included operational, training, and service manuals. By the war’s end, the agency claimed 180 employees. By 1950, annual billings were $5.9 million but would more than triple in three years.

Satellite offices opened in Windsor as well as in New York City, Chicago, and Los Angeles. Among the new clients were American Steel Wool Manufacturing Co., Lake Central Airlines, and Eljer Industries Co., the maker of plumbing fixtures.

“So, I grew up in the home of one of Detroit’s most prominent Mad Men,” Ross Roy’s youngest son, Rex Roy, wrote in a LinkedIn post. The 1984 graduate of the University of Michigan attested, “I’m old enough to remember the cocktail parties, the glamour, him getting picked up every morning in a limousine.”

The chauffeured car was a 1960 Imperial LeBaron Southampton, in black, with stainless-steel roof inserts and custom blue wool upholstery. Rex Roy was commenting on the social channel about a photo of his father’s office. The large, paneled suite included a bathroom with a shower. Ross Roy would sometimes spend the night on the davenport, as he termed it, knowing that fresh linen and clean clothes were on hand. “If you look closely,” Rex explains, “you can see the staining on the pillow from the hair oil men used in the 1940s and ’50s.”

Ron Loeffler, who studied at the College for Creative Studies, hired on as a Ross Roy art director in the mid-1960s and stayed 30 years. He found the company divided into two departments: “regular” advertising and the Chrysler group. “Ross Roy was very passionate about Chrysler,” the retired Loeffler says. “I didn’t do much for Chrysler. We had 20 or 30 different accounts.” He spent about 12 years of high involvement on La-Z-Boy and remembers trips to the company in Monroe and to factories in North Carolina.

Two incidents from Loeffler’s experience reveal the agency’s family feel. One day he loaned his car to an associate to run a business errand. When an accident occurred, the company stepped in with an offer to pay for repairs. On the other occasion, during divorce proceedings, he found himself penniless, wiped out by his soon-to-be ex-wife, and thinking, “Holy crap, I don’t know what I’m going to do.” He went up the ladder to President John Pingel, and the head of finance, and was able to work out a substantial cash advance that was repaid through weekly allocations from his paychecks. “It was a huge relief. I finally got things straightened out.”

Ross Roy, who was 5 feet 6 inches tall, was known for walking the five floors of the headquarters building and chatting with employees, especially those who kept hard candy on their desks. Besides continuing to grow his company by acquiring other agencies, Roy served as president of the Mental Health Association and the Greater Detroit Chamber of Commerce (today the Detroit Regional Chamber), and as vice president of the United Foundation of Metropolitan Detroit.

When he did his own driving, it was in the flashiest Chrysler. He ordered one or two new ones per year, selecting the biggest engine and always specifying his convertibles with air conditioning. When he died on Aug. 16, 1983, at the age of 85 after a short illness, his agency employed more than 500 people and exceeded $222 million in annual billings. At the visitation, he held in his casket a gold-plated Wilson T2000 tennis racket. A service was held at Grosse Pointe Memorial Church; his remains were cremated.

At the time of his death, Roy had been chairman of Ross Roy Communications, as it became known. Leaving his position as vice chairman of J. Walter Thompson, Glen Fortinberry took over in 1980 as president and CEO. Before his employment at JWT, Fortinberry had already worked next door to Ross Roy Inc.; he was on the Heinz account for the agency founded by Lou Maxon, another Detroit ad daddy.

“He knew he wasn’t going to be chairman of J. Walter Thompson,” Chuck Fortinberry says. In accepting Ross Roy’s job offer, Glen said, “As long as I’m not answering to your kids. I’ve got to have autonomy.” Ross Roy responded, “It’s your baby. Here’s the keys. Have at it.”

On Fortinberry’s first day, Bud Liebler was outbound after three years as senior vice president on the Chrysler account. “I had come from Ford,” recalls Liebler, who today is president of Liebler Group, a strategic communications firm he operates with his son, Patrick, at another family enterprise, The Whitney restaurant in Detroit. “(At Ford) everything’s all buttoned up, every office looks like every other office, and all that stuff. Not Ross Roy. I mean, you’d hear screaming in the halls, every office was different, they were all personalized. It was a wonderful place to work.”

Liebler turned over his company car, a Chrysler Fifth Avenue, to Fortinberry and went on to run Chrysler’s marketing and communications operations — by any measure, an incomparable 20 years of automotive showmanship. He also served as president of the Adcraft Club of Detroit, which boasted more than 4,000 members and was the oldest and largest chapter of that national organization.

By Liebler’s recollection, Fortinberry had mostly lost his Mississippi accent, but there was just enough of it for schmoozing. “He knew a lot of people, was friendly with a lot of people,” Liebler says. “He would stick his head in the door to say, ‘Hello, how are things going?’ He let his account managers run the accounts, and he ran the business — and he maintained the relationship with Lee.”

Running the business entailed the hot pursuit of new properties and the formation of Ross Roy Group. Ross Roy had sold his stock back to the company, leaving Fortinberry with a free hand. Until now, one of the biggest acquisitions had been in 1960, when Ross Roy merged with the Detroit agency Brooke, Smith, French & Dorrance. Pingel came along with the deal and took over as president in 1964. More acquisitions followed in the 1970s, and Ross Roy Inc. grew to be the 19th-largest agency in the country.

Fortinberry’s push for integrated services led to a 1987 headline in The Detroit News proclaiming, “Ross Roy, Franco tie the knot.” The stake in Anthony M. Franco Inc. — to be completed in 1990 with full ownership — gave Fortinberry the public relations component that he sought. Meanwhile, in late 1985 and early 1986, Fortinberry landed Griswold-Eshleman Co. of Cleveland, the largest agency in Ohio, and staked a claim in New York by grabbing Calet, Hirsch & Spector, whose client roster included Alitalia, Clairol, and Toshiba.

“We feel we can use his (Fortinberry’s) personal talent in helping us grow,” Calet’s co-chairman and CEO, Larry Spector, told The New York Times. “We need someone who talks the language of these guys.”

With 500 employees overflowing from the Detroit headquarters, Ross Roy Group was the second largest agency in Michigan, behind Campbell-Ewald, famed for its Chevrolet business. Renting office space here and there in the neighborhood resulted in “the Ross Roy Monopoly board,” as people joked.

In a bid to consolidate everyone on a campus, Fortinberry looked at six acres along the Detroit River that were owned by the city, but according to son Chuck, Mayor Coleman Young said, “No, we don’t want your office building. We’re going to build hotels and casinos.”

BetaWest Inc. in Denver got the option to develop the site, but nothing ever materialized and the land was eventually sold to General Motors Co. as part of its acquisition of the neighboring Renaissance Center in 1996. Part of the property was used for the Detroit RiverWalk, operated by the Detroit Riverfront Conservancy.

Glen Fortinberry said at the time, “Screw ’em, I’m moving to Bloomfield Hills.” Hobbs + Black, of Ann Arbor, designed the low-slung, granite-and-glass, cubes-colliding-with-cubes building on a wooded parcel at Woodward Avenue and W. Long Lake Road.

“All of this may have seemed pretentious coming from a company best known for churning out Chrysler brochures and Kmart commercials,” the Detroit Free Press jibed. The official cost was $8 million, although a company spokesman said that amount was “low.”

Before his death, Fortinberry had been negotiating with Omnicom Group about the sale of Ross Roy. Omnicom, a huge holding company in New York, had formed in 1986 with the merger of BBDO Worldwide and two other large agencies.

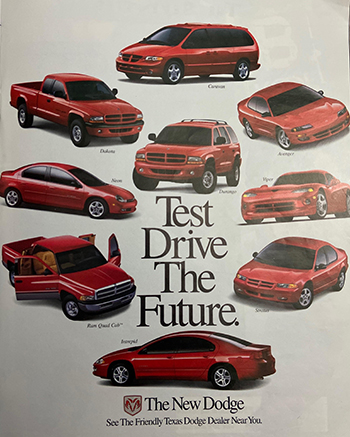

In Detroit, BBDO was executing the brilliant campaign “The New Dodge.” Tim Copacia, BBDO’s former head of account services, says, “I worked very closely with Dick Johnson and the entire creative team to bring that new, revitalized Dodge brand to market in 1993 with the launch of the Intrepid. Because that vehicle was so unique (cab-forward design), we took a completely different approach, which was to focus on the individual details.” Or not so different: It was Ross Roy’s product-knowledge tactic with red cars, white backgrounds, serif type, and the commanding actor, Edward Herrmann, as spokesman. “Dick did a masterful job,” Copacia says.

Two months after Fortinberry’s death, Copacia came over to Ross Roy as executive vice president. “Believe it or not, I was surprised about the shape of the company after I joined,” he says. “Really, it was a jewel, and regardless of the financial situation at the time, strategically, it meant an incredible amount to BBDO and Omnicom.” In 1995, the giant acquired the jewel in what Copacia saw as a good deal for stockholders.

Meantime, especially after the “information superhighway” of the internet opened up in 1996, he led the company on a mission to become “a digital force in America.” Adding a new, almost incomprehensible wrinkle two years later, Daimler-Benz acquired Chrysler Corp. in a move billed as “a merger of equals.”

Seeing changes in the industry, Copacia, today an executive vice president at J.D. Power in Troy, sold Omnicom’s leader, John Wren, on the idea of changing the agency’s name from Ross Roy to InterOne Marketing Group. It was presented as “a new name for a new millennium.” After unveiling the change of corporate identity in 2000, the next step was for InterOne to move from the Bloomfield Hills building to shared space with BBDO in Troy. At the same time, Bud Liebler was about to leave DaimlerChrysler amid a corporate-wide cost-cutting effort. “We consolidated all our advertising with BBDO — or Omnicom, whatever the hell it was called by that time,” Liebler recalls.

One of the changes was Martin Levine’s move from vice president of the Chrysler-Plymouth-Jeep division to BBDO’s PentaMark subsidiary, created to coordinate media planning and buying. So-called “experiential” marketing would be an emphasis. According to Copacia, Levine “was the worst thing that could ever happen to the agency and certainly, in my opinion, was a key to what happened to me and InterOne.” Copacia was out by 2003; the agency was eventually dissolved. “Fast-forward a couple years after I left, all of it was gone and 2,200 people lost their jobs in Detroit.”

It’s a bitter tale of the emphasis on bottom-line results and of moving targets amid continuous reorganization. “You have a lot of individual specialists working together under this cohesive brand or brands, and supporting Chrysler business and all their brands,” Copacia says.

In the end, the accumulated value of their effort was stripped away, and those specialists were scattered to the wind. Lee Iacocca was ironically prophetic in his memorial of Fortinberry when he said, “A man doesn’t live for 65 years, and touch so many people, and then a curtain comes down, and that’s the end of it. It doesn’t work that way. There’s too much left. Too much of the business he built. Too many of the friends he made. Too much of what he was.”

Back at Ross Roy’s old Jefferson Avenue building, Parducci’s “Town Crier” sculpture had plenty of reasons to bawl.

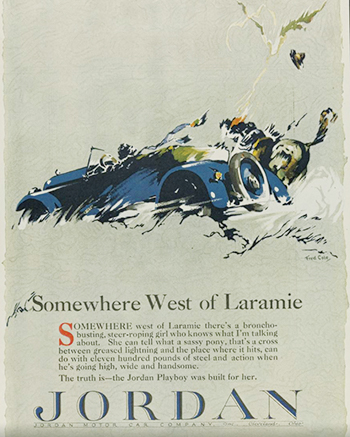

Somewhere West of Laramie

Before Ross Roy set up shop in Detroit in 1926, two approaches were already established for car advertising. One was based on snobbery.

Before Ross Roy set up shop in Detroit in 1926, two approaches were already established for car advertising. One was based on snobbery.

Theodore MacManus penned his classic, “The Penalty of Leadership,” in 1915. “In every field of human endeavor, he that is first must perpetually live in the white light of publicity,” the ad began. It warned the reader to be ready for envy and copycats. This ad ran once in The Saturday Evening Post, never even mentioning Cadillac Motor Car Co. — but everybody knew.

The best example of the second approach came from a writing session aboard a train crossing Wyoming. Entrepreneur Ned Jordan had just glimpsed a woman riding on horseback beyond the tracks and felt inspired.

Prior to the United States’ entry into World War I, he had started Jordan Motor Car Co. of Cleveland; by 1923, his hottest model was the Jordan Playboy. The roadster’s slinky shape warranted a promotional push. In “Somewhere West of Laramie,” Jordan defined the target customer. “The truth is — the Playboy was built for her. Built for the lass whose face is brown with the sun when the day is done of revel and romp and race.”

Prior to the United States’ entry into World War I, he had started Jordan Motor Car Co. of Cleveland; by 1923, his hottest model was the Jordan Playboy. The roadster’s slinky shape warranted a promotional push. In “Somewhere West of Laramie,” Jordan defined the target customer. “The truth is — the Playboy was built for her. Built for the lass whose face is brown with the sun when the day is done of revel and romp and race.”

Ross Roy said phooey to all that and went with his product-knowledge method of a feature-by-feature comparison of automobiles. It was well-suited to Walter Chrysler’s emphasis on high-quality engineering.

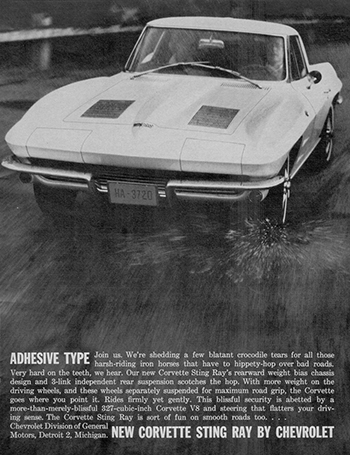

A subsequent landmark ad was “Adhesive Type,” by David E. Davis Jr., who presided at Campbell-Ewald in Detroit in the early 1960s. Independent rear suspension was a notable feature of the new Chevrolet Corvette Stingray, and Davis’ copy highlighted this advance with a tone of droll sophistication.

“The New Dodge,” Dick Johnson’s BBDO campaign for the 1993 Dodge Intrepid, took a cerebral, postmodern approach, excluding the copy block and relying on the ad line. An example from late in the campaign was “Test Drive the Future.” Different, yes, but it clobbered the reader with the claim.

“The New Dodge,” Dick Johnson’s BBDO campaign for the 1993 Dodge Intrepid, took a cerebral, postmodern approach, excluding the copy block and relying on the ad line. An example from late in the campaign was “Test Drive the Future.” Different, yes, but it clobbered the reader with the claim.

After 2000, print advertising began to receive less and less emphasis, and a great tradition gradually faded.