It’s hard to believe today — when advertisements for lawyers and their services are as ubiquitous as spring potholes — that, in the not-too-distant past, legal advertising could lead to disbarment. However, once the U.S. Supreme Court threw out the ban of all 50 state bar associations against advertising in 1977, lawyers like Sam Bernstein tried in earnest to persuade Detroiters to call, er, Sam.

Initially, it wasn’t much of a panacea. In those early days, there were no Call Sam Studios on Tigers Baseball. There were no heartfelt client testimonials on local TV.

“We started advertising first in the Yellow Pages,” says Mark Bernstein, Sam’s son and president and managing partner of The Sam Bernstein Law Firm in Farmington Hills. “My dad tells stories of how he would go down to the Yellow Pages building (in Detroit), which had a neon sign with the Yellow Pages logo, and they didn’t have any salespeople. You had to wait in your car until they would open the building, and you had to sprint into the building to get in line to buy your Yellow Pages ad.”

Today, trial lawyers are among the most recognized faces in the metro area, and they spend lavishly to make sure it stays that way. Sam Bernstein, Geoffrey Fieger, Joumana Kayrouz — they’re as familiar as your next-door neighbor, at least those of them who can afford to advertise on TV, or have their faces adorn billboards and the sides of buses.

Still, there’s more to selling a service or building a brand than just “getting your name out there.” Name and face recognition may be necessary, but it’s not sufficient to claim and hold a share of a market when no one can predict who is going to become a client. Who

actually plans to slip and fall, get in an auto accident, or split their head open? In order to attract people when the unexpected happens, lawyers have to cast a wide net and choose brand identities with mass appeal, all the while distinguishing themselves from the competition.

Southfield-based Goodman Acker, for example, discovered after a recent review of their strategy and results, that a major change was needed. For nearly 10 years, Goodman Acker had contracted for the use of ad material featuring actor William Shatner. The ads, which are marketed nationwide and localized for the firms who use them, got results for years — but they came with a stiff price tag. And once the Star Trek actor turned 80, it wasn’t clear he was still effective, or that enough of the audience knew who he was.

“We had a number of different thoughts about what was working and what wasn’t, and we came to the conclusion that the most authentic approach was to let (potential clients) see who they were hiring,” says Jerry Acker, a partner who recently began starring in a series of TV ads that replaced the Shatner spots.

Even as Acker serves as the star in the commercials, partner Barry Goodman emphasizes that the goal isn’t to turn anyone at the firm into some sort of local celebrity. “We felt that a lot of the advertising is ego-driven,” Goodman says. “We want to be there to be trusted, because that’s what we think we are. We care about our clients. It’s our mantra every day here, and we (believe) it’s important to project that.”

Goodman and Acker acknowledge they can’t outspend all of their competitors, particularly the Bernsteins, whose firm is now the largest buyer of legal advertising in Michigan. So they decided nearly a decade ago they had enough of taking the leftovers from firms that advertised heavily and then would refer certain less desirable cases to Goodman Acker for a healthy finder’s fee.

While the legal ad market is highly competitive, it’s also fairly diverse in terms of the advertising strategies. And the firms themselves are the first to admit they employ a lot of trial-and-error in seeking the most effective approach.

“It’s a lot of guesswork,” says Mike Morse, founder and principal of the Mike Morse Law Firm in Southfield, which specializes in personal injuries, especially automobile accidents. Apart from having his name appear atop a large office building where he works along Northwestern Highway, Morse has become a fixture on local television.

“After 30 years on TV, I’m not on billboards and I’m not on radio,” Morse says. “I’ve dabbled in them, but I just didn’t love the response I got. And when I pulled off of them as an experiment, I didn’t see the needle move at all.”

As a result, he decided to focus almost exclusively on television — but even there, the decision about where and when to do an ad buy is often based on instinct.

“I’m on Empire right now (on FOX), which is a prime time thing,” he says. “I’ve done Super Bowl ads two years in a row. I like special sporting events, and American Idol from time to time. It’s kind of a gut thing. Anybody can be in a car accident, so you don’t know what they’re watching. That’s why we take kind of a shotgun approach. American Idol, I just think that’s a good show. I don’t have a great answer for the shows I tend to pick. Someone told me Empire is a good show, so I said I wanted to be on that show.”

Morse is far more strategic, however, about his messaging. Both his website address and his toll-free phone number emphasize the phrase, “MIKE WINS.” He says he’s trying to get across to prospective clients that they’re getting a firm with lots of resources, as well as a leader who personally gets involved in every case.

“We’re keeping 90 percent of our cases as opposed to our competitors (referring cases to other firms), and if we take a case, we’re getting money on 97 percent or more of the cases,” Morse says. “We’re winning. And I’m not just a figurehead. I’m actually in the trenches. I’m doing arbitrations and mediations with the clients every single day. That’s kind of different and unique, and I bring that out in my commercials and let people know. I’m not retired and I’m not a figurehead.”

Conversely, the Bernsteins are well aware of the fact that their familiar family name provides the basis for a branding strategy that brings a return on their massive investment of advertising dollars, particularly since they became the lead sponsor of Detroit Tigers baseball television broadcasts in the region and state.

“Every firm needs their own voice and, for us, there’s no question that our family is an important representation of our identity,” Mark Bernstein says. “It strongly resonates with our clients and prospective clients, and it’s distinguishing relative to our competition, who we respect. It’s just that different people have different ways of representing themselves.”

Bernstein is aware of the fact that some people — especially those who watch Tigers games — can find themselves susceptible to what you might call “Bernstein burnout.” Although he recognizes that so many spots and so much visibility can create the danger of oversaturation, Bernstein believes the firm’s particular approach to TV spots is easier for audiences to take in higher volumes.

“I think the message we use allows us to have higher-frequency traffic placements,” Bernstein says. “There are some types of ads that don’t wear very well. We think our message respects the viewer and gives dignity to the work we do, and to our clients. It tells honest, thoughtful stories about our work. If you’re screaming the whole time, you can’t run that frequently.”

Screaming? Who screams?

Well, maybe no one, but there is a lawyer in town who thinks the measured messages coming from his competitors are a bit, shall we say, unauthentic. And it will probably not surprise anyone in metro Detroit to know that this lawyer’s name is Geoffrey Fieger.

“I don’t ploy, and I don’t beg,” says Fieger, principal of Fieger Law in Southfield. “I make political ads, and they’re reflective of who I am. I’m making political statements in my ads, and it happens to be synonymous with who I am, so it’s not just the nonsense that you see with other lawyers. All this, ‘I care, I really do a good job, you can trust me.’ That’s terrible, really. It’s nonsense. And it’s a lie, too. Morse says he gets the biggest settlements in Michigan. He does not. He’s never tried a case. Joumana barely speaks English. She’s never tried a case.”

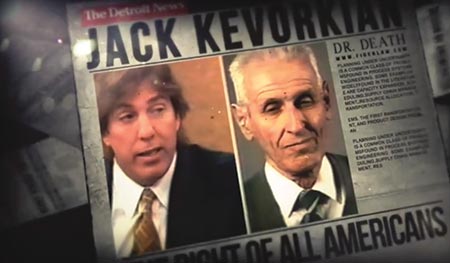

Strong words, but if you question Fieger about it, he’ll tell you the polite approach of others is fake and insincere — or at least it would be if he tried it, because it’s not him. Of course, Fieger’s brand identity didn’t solely derive from a decision to aggressively advertise, as he will be the first to tell you. Sometimes lawyers gain public recognition because of a particularly famous case or client; for Fieger, it was his decision to represent Jack Kevorkian, a Royal Oak medical pathologist who became a national figure surrounding assisted suicide. Fieger’s ad strategy today is designed to build on that notoriety, not only in Michigan, but nationally. Still, he didn’t just fall into the opportunity. Far from it.

“Everybody always told me I wasn’t the first person Kevorkian ever went to,” Fieger says. “I was way down the line. No one would take the case because they thought it would hurt their practice, (and) it would reflect poorly on them. So they all turned it down. So when people say Fieger did this on the back of Kevorkian, that’s nonsense. But the young kids have forgotten about it. I became famous because of Kevorkian, but it’s gone beyond that.”

Today, Fieger’s advertising reflects a sort of bluntness. He figures no-holds-barred authenticity lands the kinds of clients he wants, and that’s more than enough for him. It’s one reason he says he doesn’t actually put that much strategic thought into his ads.

“I don’t intellectualize like that,” Fieger maintains. “I’m just doing what Geoff Fieger wants to do, and it comes out. It would be like saying to The Beatles, ‘How do you write a hit pop song?’ They don’t know. And if there was a formula, I wouldn’t follow it, anyway.”

Of course, a series of ads that sets you up as the defender of the downtrodden against the privileged and powerful could be seen as quite strategic and even calculated, but don’t try telling that to Fieger.

If the Kevorkian case made Fieger famous, Joumana Kayrouz, a native of Lebanon who actually does speak fluent English, had no such opportunity to help her burst onto the scene. When she started her firm in 2001, Kayrouz lacked name recognition and a brand identity. Unlike many lawyers, who choose to spend heavily on television to build name recognition, Kayrouz chose initially to go almost exclusively with billboards. That effort culminated two years ago when her face was seen on 160 billboards around metro Detroit, in addition to almost every publicly operated bus.

The strategy, according to her marketing director Paul Schmidt, was to establish heavy name recognition first before branching out into forms of advertising that focused more on services.

“We decided the only way to make the billboards really work was to saturate the market,” Schmidt says. “It wasn’t so much for lead generation as it was to create a brand that people recognize. Everyone knew Sam Bernstein. Everyone knew the other names. But how do you make your name in a saturated market? So for a few years we just saturated (the region) with billboards, and the story was that she was everywhere.”

Having established brand recognition with billboards, Schmidt says the firm is now changing its focus to more television and online presence, and will closely track how well the effort generates leads. Kayrouz told the Metro Times last year that her annual advertising budget is $4.3 million, which ad experts say is still far less than market leaders Bernstein and Morse, who don’t release their spending totals. Schmidt thinks the firm spends more than enough to get the results they need.

“Our people who are taking the calls will ask a series of questions when a client calls in for the first time,” Schmidt says. “From there, we’ll determine how they heard about us. We keep records on all that and then match them up again. We had a client in Joumana’s office not too long ago, and we asked how he heard about us. He said (it was) the ad talking about (how) the insurance companies might tell you some of your benefits and not all of your benefits, and he said that had happened to his wife when she got in an accident.”

The law firms that are carefully tracking their results are obviously looking to make sure they get a return on their investment, yet the biggest player in the market might never have taken legal advertising to such a height if not for the fact that he initially failed to pay attention. According to Mark Bernstein, his father’s first major ad buy back in the 1980s on channels 20 and 50 was slow to generate results, and could have easily been axed from the budget. “But he went and started doing a trial that lasted five or six weeks,” Mark Bernstein recalls, “and while he was in trial, he didn’t realize the phones weren’t ringing and nothing was happening. If he’d been in the office, he probably would have canceled it.”

As the weeks — and the trial — went on, the Bernstein spots started to make an impact. By the time the trial concluded and the barrister returned full time to the office, the phones were ringing and leads were coming in. So the decision was made to stick with TV as a way of persuading people to call Sam.

More than three decades later, the campaign still works. db

Hat in Hand

If a law firm has millions of dollars to spend on advertising, media saturation becomes a pretty plausible option for promoting services.

The vast majority of law firms, however, are small; many have only one attorney, with a business model designed to maximize billings while minimizing overhead. Although that tends to put massive media buys out of reach, it doesn’t mean lawyers can’t be effective marketers. It just means they have to be a little cleverer than the next guy.

Royal Oak-based attorney Justin Smith, who specializes in eviction cases for landlords, says he’s gotten results by taking a somewhat more audacious approach to branding his practice — one that stays professional, but nonetheless cuts right to the heart of what his clients are looking for.

“I’m a niche law business, and I don’t have that much of a budget, but you can do a lot by really understanding the passion and the mentality of your target audience,” Smith says. “People tell me it really sold them when I put on my website: ‘Get the deadbeats out and make them pay.’ That spoke to what they wanted.”

Smith chose TheLandlordLawyer.com as his Web domain, and worked to make sure the site would be seen even without a huge promotional budget. “I’m an insomniac, so I do everything I can to get the search engine optimization,” Smith says. “That means going on third-party sites and answering free questions with my name on them, creating pointers back to my page.”

He’s also decided to have a sense of humor about the realities of what sometimes happens as a result of his work. A few years ago, Smith produced baseball hats with the firm’s Web address and the phrase, “We evict on Christmas Eve.”

Over the line?

“I’ve had some of my clients wear the hat when they’re signing up their tenants,” Smith says. “Of course, you want to have a smile on your face when you wear it, but (tenants) remember it. I can go to VistaPrint and produce a hat for $11.”

It’s not the sort of strategy that will get you recognized by millions, but those who see it aren’t likely to forget it. — Dan Calabrese