More than a decade ago, when controversy began to give way to inevitability, gaming proponents in Michigan exuded confidence that casinos would bring any number of benefits to the region and to investors, including Indian tribes, who would own most of them.

For the tribes, casino revenue would help pay for everything from education to medical care for their members. And for the various regions of the state, particularly the Detroit area, casinos would be a source of jobs and would help keep residents’ entertainment dollars in the region rather than seeing them flee to Windsor, Atlantic City, or Las Vegas.

The notions of problem gambling and crime were hotly debated issues, but few questioned that the casinos themselves would make money.

That was then. As with so much else people thought they knew about economics, Michigan’s casino market has become the latest illustration of the maxim that there’s no such thing as a sure thing.

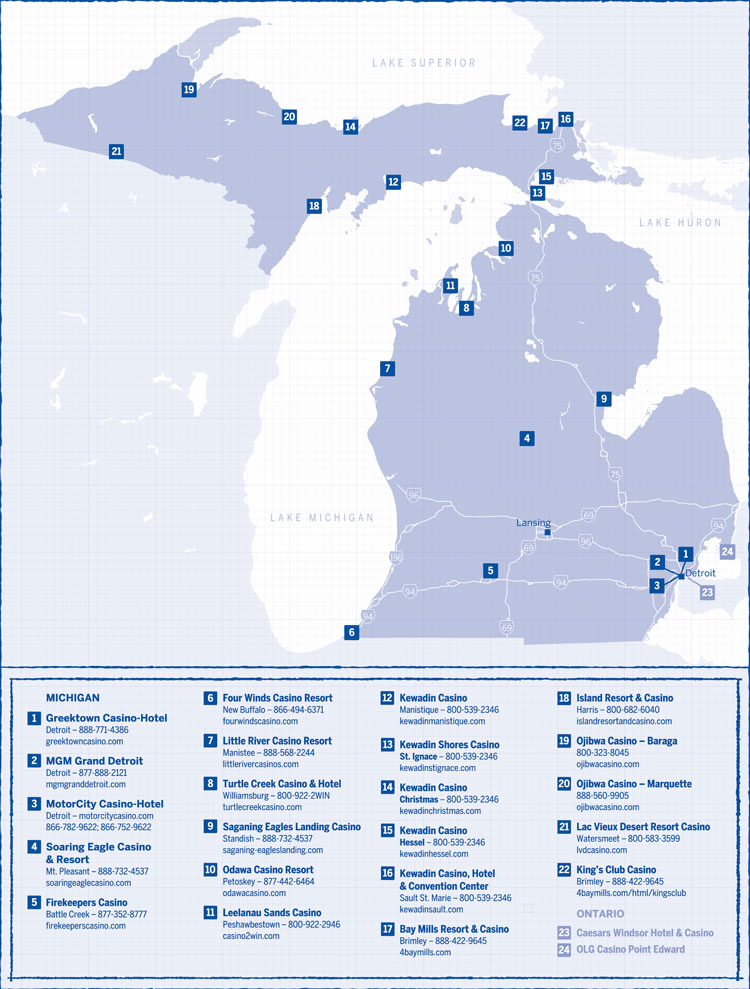

Michigan’s 22 casinos all remain in operation, and a 23rd is on the horizon. No one is suggesting that Michigan casinos have no future, or even that they don’t have a good chance of long-term success. But more competition is right around the corner.

“Compared to other states, Michigan isn’t as saturated as it relates to the percentage of slot machines to population,” says Jake Miklojcik, president of Michigan Consultants, a Lansing financial feasibility and public policy group, and a member of the Greektown casino management board.

Michigan’s economy has spared no one entirely, and many of the glitzy operations that were once considered cash cows have enacted sizable layoffs. A casino in bankruptcy is rather unusual, but it happened here in Detroit with Greektown Casino, which is scheduled to emerge from Chapter 11 this summer.

That, of course, will come as no surprise to anyone who’s paid attention to the Atlantic City market, where almost every casino is currently in some form of restructuring. Indeed, Donald Trump has practically turned the strategically engineered bankruptcy into a business strategy (with billionaire investor Carl Icahn’s money).

But it wasn’t what most expected when Michigan voters approved casino gaming back in 1996.

And, at least for some Michigan casinos, the challenge is about to become even more pronounced. Last November, Ohio voters passed a gaming ballot initiative allowing casinos in Cleveland, Cincinnati, Columbus, and Toledo. Livonia-based Quicken Loans Chairman Dan Gilbert, along with Penn National Gaming Inc., hold the contracts to develop what many fear will only intensify the challenges for Michigan casinos. Gilbert will build in Cleveland and Cincinnati, while Penn gets both Toledo and Columbus.

The prospect of new competition, of course, always prompts those with a stake in the game to protect their market share, which is why Michigan casinos certainly weren’t rooting for the Toledo proposal to pass. But now that it has, Michigan casinos at least have the luxury of time to develop strategies while Gilbert and Penn sort out the details.

If Michigan casinos rise above the Ohio challenge, they will prove that their business model is exceedingly durable. But there’s work to do first.

In 1996, state voters approved a referendum allowing for three casinos in Detroit. That paved the way for the eventual opening of Greektown Casino, MotorCity Casino, and MGM Grand Detroit.

By way of a separate compact between the state of Michigan and various Indian tribes, a total of 19 other casinos operate at various locations throughout the state. Major players in the tribal casino market include the Kewadin Casino chain, which operates five casinos in the eastern Upper Peninsula, the Soaring Eagle Casino in Mount Pleasant, the Little River Casino in Manistee, and the Leelanau Sands Casino in Suttons Bay.

The development of new casinos has often been tinged with controversy, and that was certainly the case with the Gun Lake Casino in Baldwin, near historically conservative Grand Rapids. Fueled by a combination of philosophical objections and concerns for economic competition, local opposition groups — particularly the Grand Rapids Area Chamber of Commerce — fought the Gun Lake development for years before capitulating.

Still, given the need to secure financing and building permits, the $200-million project isn’t expected to open anytime soon. But once the casino opens (likely in late 2011), it will directly compete for gamblers within a five-hour driving radius, considered the sweet spot for drawing weekend visitors and tourists.

That, along with Battle Creek’s new $300-million Firekeepers Casino — which opened last summer with 2,600 slot machines, 120 poker seats, and more than 70 table games — will affect Detroit’s casinos even more.

For 2009, Detroit’s three casinos reported a combined $1.3 billion in revenue, down 1.5 percent from the previous year. In comparison, thanks to a falloff in tourism and air travel, Las Vegas and Atlantic City posted double-digit declines last year.

Rising promotions helped increase revenue for Detroit’s casinos in November and December, a trend that will likely continue. Last year, MGM Grand led the market with $547.8 million in revenue, followed by MotorCity Casino ($445.8 million), and Greektown ($346.0 million). Annual gaming taxes paid to the state increased slightly last year to $122.3 million, up from $121.0 million in 2008.

Only Greektown’s 2009 performance represents an improvement over the previous year (in which Greektown fell into Chapter 11). Last October, Greektown’s owner, the Sault Ste. Marie tribe of Chippewa Indians, lost control of the casino to its major creditors, led by investment firm Merrill Lynch.

Randy Fine, former CEO of Greektown Casino — a role he played via his Las Vegas-based consultancy The FinePoint Group — says the casino had to re-evaluate its positioning vis-à-vis the other Detroit casinos, and believes it settled on a good and distinctive strategy.

“If you look at the Detroit market, MGM’s brand is super high-end luxury,” he says. “MotorCity’s brand is sort of urban, and Greektown didn’t have a brand. Greektown’s brand was trying to say, ‘We’re nice, too. We have clubs, too. We have restaurants, too.’ … There are many casinos who’ve used this strategy — [but] never with success.”

Greektown’s new brand positioning, Fine says, is affordable gaming value, with offerings like $99 rooms and $9.95 buffets. “It appeals to average folks who just want to have a good time,” he says.

But how much will a trip to Toledo appeal to the same people?

The coming casino development in Toledo is far from defined, but some likely limits to the appeal of the casino are already known. Struggling Toledo-area hotel operators, whose current occupancy rate is only about 45 percent, successfully campaigned to forbid the casino from offering guest lodging.

That puts the Detroit casinos at a disadvantage, since each operates a 400-room hotel as prescribed by state law. What’s more, the Detroit casinos are required to double their hotel capacity if they exceed 60 percent occupancy levels over a prescribed period of time. Without the covenant, the occupancy rate would likely rise.

In turn, the city of Detroit institutes a 2.5 percent tax on every slot jackpot above $1,000. There’s no comparable tax in Ohio. But on the plus side for casino operators in Detroit, each of the casino projects in Ohio requires a $50-million license fee. In Detroit, there was no application fee.

Fine, a seasoned consultant to the casino industry, is skeptical of Penn National’s ability to draw many metro Detroit casino-goers to Toledo. “I think the model of gaming that was passed in Ohio was as good for Michigan as it could be,” he says. “When you grant someone a monopoly in Toledo, I believe the optimal strategy for Penn National is to build the cheapest casino you can. You put in a ton of slot machines, open the doors, and wait for the locals to come. … You don’t have to work very hard if you don’t have a lot of competition.”

According to Fine, that was reflected in the Detroit casinos’ lack of opposition to the Ohio proposal. “First, a very small percentage of [the] business comes from Ohio,” he says. “It’s not a lot of money. If you look at the amount of money that was spent against the Ohio referendum, I believe the grand total the three [Detroit] casinos spent fighting that referendum was zero. Casinos in West Virginia spent $25 million. So you’d think that if we were worried about it, we would have spent money against it — [but] we didn’t.”

Still, Detroit casinos are not so cavalier about the Toledo challenge that they’re not mulling their strategic options.

MotorCity Casino COO Rhonda Cohen says her organization is looking to counter Toledo’s appeal with added value, to keep nearby core customers in the fold. “The steps we’re taking will be to market to the area for packages that will include the type of leisure stay you can have with us,” she says. “We’re packaging things and making them value-added — spa discounts or theater tickets.”

At the same time, Cohen believes Penn National’s eventual development will face a significant hurdle as a result of gaming taxes. The ballot initiative, called Issue 3, mandated a 33-percent tax on all casino revenue in Ohio. By contrast, Detroit casinos pay 24 percent of their net winnings, about half to the state and half to the city.

“Due to their significant tax burden, [Ohio casinos] aren’t going to have the ability to build what we have with all the amenities,” Cohen says. “So they should lose some gaming visits, including day trips, from people from our area.”

Grant Govertson, a gaming industry analyst with Las Vegas-based Union Gaming Group, is impressed with how Detroit’s casinos have weathered the storms thus far, but believes they have serious challenges ahead of them.

“Despite broader economic conditions and those specific to the greater Detroit area, the three Detroit casinos have held up relatively well,” he says. “This is especially true for Greektown. However, on a longer-term basis, we believe that gaming expansion in Ohio is likely to have a negative impact on Detroit casinos. Given the proximity of Toledo to Detroit, Penn National Gaming’s casino in that city would become an alternative destination for communities to the south and west of Detroit.”

On the other hand, Govertson doesn’t expect the Toledo developments to pose any threat to Michigan’s outstate Indian casinos. But not everyone agrees, and even some of the Indian casino operators are assuming they’ll need to take action to counter the competition from Penn National. After the Ohio vote, Sean Barnard, general manager of the Odawa Casino Resort, issued a statement that read in part: “Most of our business comes from within our state, and only a fraction comes from Ohio. The bigger issue for us is the closeness of those new properties to our Detroit customer base, which accounts for thousands of visits per year. Toledo, for instance, is just 60 miles away from Detroit, and Cleveland is 100 miles closer to that market than we are. The Ohio and Detroit business that could be lost is worth millions [of dollars] to us and our sister Native American casinos. More casinos will ultimately grow the business as a whole, but these new players will obviously do what they can to aggressively attract our customers away from us.”

Steve Ruggiero, a casino industry analyst for Stamford, Conn.-based CRT Capital Group, agrees with Barnard. “Gaming patrons will prefer to travel shorter distances to a casino, if possible,” he says. “The Ohio casinos will be new, but so, too, are the Native American casinos that have been built and opened in Michigan. So newness isn’t a defining characteristic.”

Ruggiero believes that higher casino taxes in Ohio, as well as in Indiana, will put those states’ casinos at a distinct pricing disadvantage.

Even so, Barnard believes that no Michigan casinos can afford to underestimate the competitive threat. “All of us will have to ensure that we’re providing our guests with an experience that does more than just maintain their loyalty,” he says. “We’ll all be forced to spend more on print advertising, outdoor billboards, radio advertising, special events, and direct mail. Quite simply, our costs will rise, and we would all be wise to start working on it now and not regretting a lack of proactive marketing later.”

Michelle Couschour, public relations director for Kewadin Casinos, agrees that Toledo could compete even with UP-based casinos for day-trippers. And, she adds, the same challenge sometimes presents itself from the north. With the post-9/11 tightening of border-crossing requirements, Kewadin had to work harder to maintain a steady stream of business from Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario.

“With the whole passport thing … we’ve been working with the Canadian market, making sure we’re offering better incentives and paying more attention to their issues,” she says. “We’ve definitely seen a decrease in overall traffic, but our revenues have stayed pretty level, so we’re happy with that.”

But how has the casino been able to maintain revenue if traffic is down? Couschour says it’s a product of more local residents staying closer to home, as the recession has cut into disposable income to pay for travel. Still, Kewadin has had to tighten its expenses.

Complacency, however, is certainly not the order of the day. Mike Dini, interim director of marketing and entertainment for Soaring Eagle Casino, says his organization is redoubling its efforts to secure customer loyalty by using both technology and good old-fashioned people skills to cater to the needs of individual players.

“We have a group of hosts who know their players very well, and they’re able to talk with them on a daily or weekly basis and get them to come in and visit with us,” Dini says. “It’s those personal, one-on-one relationships. And we’ve applied a lot of technology.”

Dini adds that Soaring Eagle is starting to use social media techniques to build relationships with customers. “It’s just a matter of keeping up with the times,” he says. “Technology has changed things. You have to keep up with what’s applicable in the market. We don’t neglect any of our guests.”

These days, how could you?