By outward appearances, there wasn’t anything peculiar about the nondescript barbershop that unceremoniously opened its doors in late December 2008. Situated on the city’s west side in an area synonymous with violent crime, it was designed to be a place for neighborhood men to congregate and get groomed, talk sports, debate local politics, or shoot a friendly game of dice.

But this barbershop was different. For starters, the majority of men who regularly began walking through the door weren’t at all interested in getting cuts, trims, or shaves. Nor were they looking to pass the time poring over box scores in the sports pages.

Oddly enough, they did share one particular common interest: heading straight to the barbershop’s back office, where a Scarface movie poster graced its red-painted walls. As was revealed some months later, the repetitive traffic in and out of the building was more than easily explainable.

Shortly after opening, the shop’s proprietors — all undercover federal agents — began casually letting it be known that they had money to exchange for firearms. By all accounts, the scores of men who ended up taking the staff up on their offer didn’t disappoint.

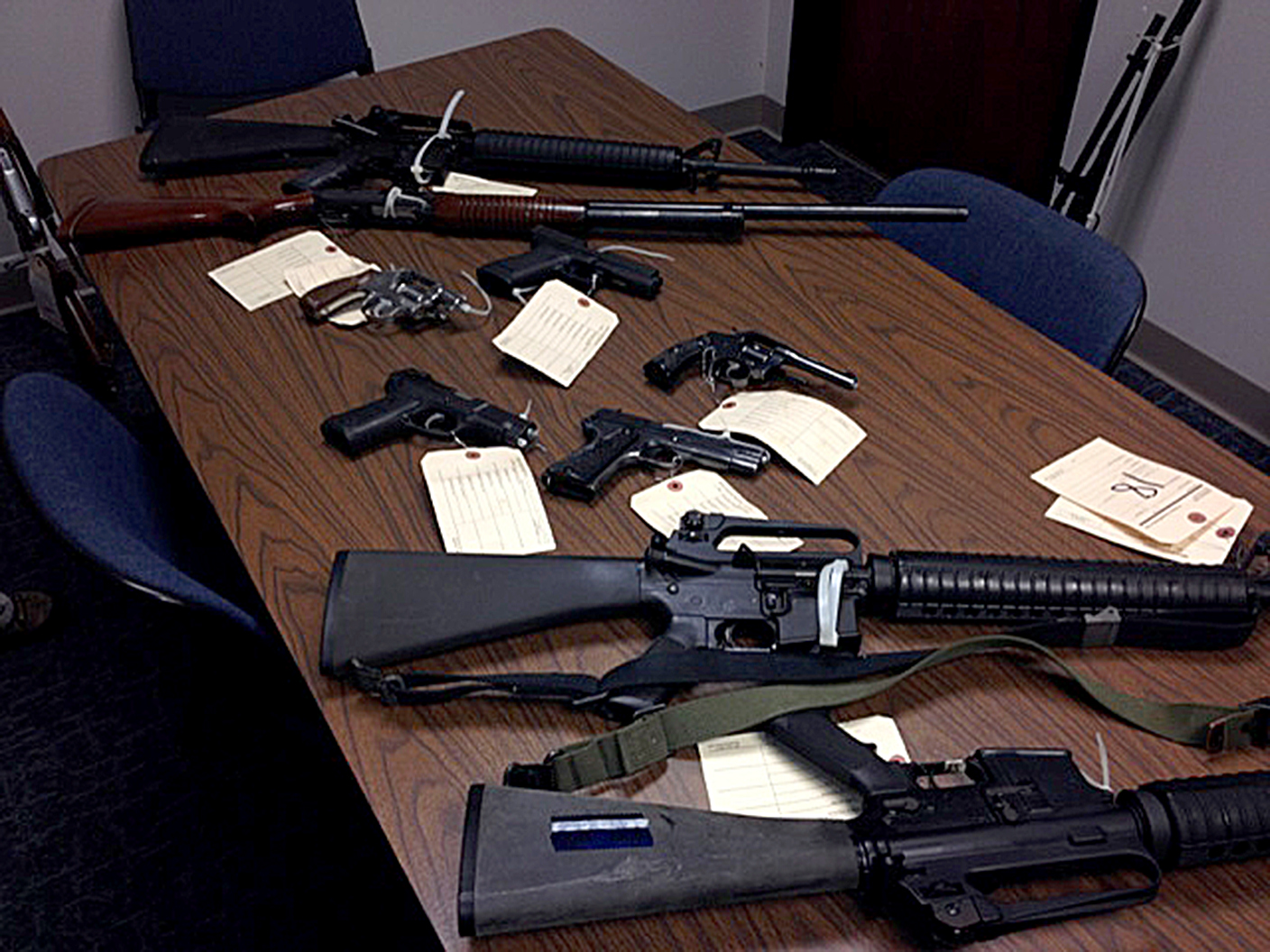

As anticipated, cold, hard cash was regularly handed over for an assortment of weapons, most later discovered to be illegal, ranging from semi-automatic handguns to revolvers, machine guns, and sawed-off shotguns.

The visitors in and out of the shop thought they were moving firearms for an easy payday, where asking prices varied anywhere between $60 and $1,000 per weapon. Instead, they were the star players in a Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives Detroit Field Division sting code-named “Operation Motown Fades.”

Guns of Detroit: A selection of gun-related crimes reported by the Detroit Police / Click Here

By the time the ATF operation was officially shut down in May 2009, some 30 arrests had been made and 60 guns were confiscated. Federal gun charges were levied against those apprehended. Over the next four years, federal cases related to the sting were adjudicated in court. Eventually, prison sentences of various lengths were handed down to those found guilty.

For those keeping score on the streets, the barbershop rouse was a true victory for the ATF Detroit Field Division — albeit a small one — in an ongoing protracted game routinely waged against those indiscriminately selling illegal firearms in the city.

More importantly, it showed the extraordinary lengths to which federal agents are willing to go in order to thwart the illicit big-money business of gun trafficking that continues putting instruments of death into the hands of some of the city’s worst actors.

While quick to point out that it would be virtually impossible to zero in on a specific number of weapons, ATF special agent and Detroit Field Division Public Information Officer Donald C. Dawkins says there are “hundreds of thousands” of illegal firearms of every conceivable type and caliber on the move inside the city’s limits.

A rough estimate becomes disturbing when delving into Detroit’s crime numbers over the last two years. In 2012, the city recorded 386 criminal homicides and 2,424 nonfatal shootings. Last year, the homicide count dropped to 333 — a 14 percent dip from 2012. The decline, while welcome, far surpasses most every city in the nation. New York City, with more than 10 times Detroit’s population, had roughly the same number of criminal homicides during the same period.

Given Detroit’s known problems with violent crime and the universal concession from law enforcement officials acknowledging an illegal gun epidemic, how did “hundreds of thousands” of weapons make their way into the hands of city residents?

Ironically, the majority of illegal firearms making the rounds in Detroit courtesy of unlawful buyers and sellers started out as the legal property of law-abiding citizens, Dawkins says. More specifically, the weapons are primarily taken during home invasions in Detroit and the surrounding suburbs. “A lot of them are (initially) legally sold,” Dawkins says. “Then they’re stolen.”

Sgt. Jeff Pacholski of the Detroit Police Department Firearms Investigation Team, a specialized six-person unit that augments ATF activities in the city, echoes Dawkins’ assessment. “The majority of firearms that are recovered in Detroit do not originate from some complex firearm trafficking ring,” Pacholski says. “Most crime guns that are recovered in Detroit were purchased legally and ended up in the hands of criminals when the firearms were stolen.”

Separate from residential thefts, additional illegal guns originate when licensed purchasers knowingly obtain — generally for cash — firearms for those forbidden by law to possess them during so-called “straw purchases.”

Once an illegal gun surfaces in Detroit, whether it’s from theft or straw purchase, all bets are off. Dawkins equates the movement to how currency travels in a free market. “It’s like money,” he says. “It gets into circulation. That firearm can change hands four, five, or six times.”

When actual trafficking — which Dawkins describes as being “big business” in Detroit — comes into play, it’s mostly thought of as nothing more than a byproduct of simple supply and demand on the streets of a city suffering from violent crime and extensive narcotics trafficking. “You have a lot of people who are into narcotics trafficking (in Detroit),” Dawkins says. “They want firearms for protection. They can (either) steal firearms, or have someone make a straw purchase for them.”

Citing past cases, Dawkins says prices can start as low as $60 for a .22-caliber revolver, and go as high as $1,000 or more for a high-powered assault weapon.

Dawkins says it’s only a matter of time until an illegally sold gun ends up being used to commit violent crimes like carjacking, drive-by shootings, armed robberies, and murders that put residents and visitors at risk. “It might not be right away, but a year or two down the road, that firearm that was sold illegally is recovered by another department at the scene of a crime,” he says.

So as not to compromise ongoing investigations, Dawkins declines to speak substantively about specific techniques the ATF uses to take on gun trafficking. He does, however, stipulate that past operations have employed deep undercover work, the use of confidential informants, and tracking data in high-crime areas where gun-related crimes are prevalent. As Dawkins tells it, Detroit ATF agents take in-depth measures to maintain a high degree of unpredictability and to be forward-thinking within the confines of the law to be successful in thwarting gun traffickers.

“We always have to stay one step ahead (of the criminals),” Dawkins says. “We have to remain innovative in our investigative approach. If it’s legal, if it’s doable, we’ll at least give it a look.”

Aside from the incalculable number of firearms obtained annually during home invasions and via straw purchases that end up being moved on the street for cash, former FBI Detroit Division special agent in charge Andrew Arena believes other, more calculated reasons may be adding to the vast amount of illegal guns being sold in the city.

As executive director of the Detroit Crime Commission, a nonprofit organization dedicated to providing analytical support to law enforcement agencies, Arena says selectively targeted gun shop robberies throughout the metropolitan area continue to provide street-level gunrunners with a “choice du jour” of handguns and assault weapons in what can best be described as a black market.

Arena says while most people who buy illegal guns on Detroit’s streets are usually satisfied to simply take “whatever they can get their hands on,” there are others who are well-versed in firearms and will only hand over cash for certain types of weapons.

Where handguns are concerned, some criminals — rather than run the risk of leaving a treasure trove of evidence behind for forensic examiners — completely avoid using semi-automatics, due to the way they eject multiple casings when fired. “There are criminals that only like to use revolvers because they don’t really leave any evidence behind,” Arena says.

Conversely, others have an affinity for assault weaponry — particularly AR-15s and replicated versions of Russian model AK-47 automatic rifles. Contrary to the belief that such weapons are hard to procure by legitimate means, Arena says there are “a fair number of assault weapons out there legally” that are stolen and put on Detroit’s streets for sale.

Arena also doesn’t entirely rule out the possibility that Mexican cartels, recognized for being able to masterfully transport narcotics and weapons up through pipelines reaching the Midwest, may be benefiting from Detroit’s illegal gun trade. “It’s possible,” Arena says. “When you develop trafficking rings that are that sophisticated, you’re going to use them to make money any way you can.”

U.S. Attorney Barbara L. McQuade, who has headed up Michigan’s Eastern District division since 2010, says her office segments the prosecution of violent offenders, felons in possession of firearms, high-level drug dealers, and gun traffickers. “We prioritize cases based on the use of guns to commit violent and drug trafficking crimes, or possession of firearms by felons,” she says. “We aggressively prosecute gun trafficking cases whenever those cases are uncovered by investigating agents.”

An advocate for “Detroit One,” a multi-task force initiative focused on quelling violent crime in the city, McQuade has prosecuted 20 cases against 28 defendants over a four-year period.

Given her prosecutorial discretion, McQuade doesn’t believe that a eries of high-profile gun trafficking cases on their own — where penalties would range from five years and up if convicted — would make a negligible difference in discouraging the activity.

The Eastern District instead concentrates its efforts on what McQuade believes to be the root cause of gun trafficking occurring inside of Detroit: Drug traffickers who acquire scores of illegal weapons to protect their operations. “Prosecuting drug traffickers and obtaining significant sentences can have a deterrent effect on the sale of illegal guns,” she maintains.

By strictly enforcing federal gun laws and working collaboratively with local law enforcement agencies, especially as it relates to prosecuting violent drug offenders, McQuade hopes the Eastern District can be a catalyst for change on Detroit’s gun-infested streets. “We work collaboratively with the Wayne County Prosecutor in gun cases. We have made federal prosecution of violent gun offenses a high priority, and we hope the long sentences we’re able to obtain in federal court will have a deterrent effect in the long run,” she says.

One case illustrates the multipronged strategy. A few years ago,  Terrance Coles made his money supplying Detroit’s streets with illegal guns. Today he resides in a federal penitentiary 90 miles south of Buffalo, in upstate New York, serving out a 15-year sentence.

Terrance Coles made his money supplying Detroit’s streets with illegal guns. Today he resides in a federal penitentiary 90 miles south of Buffalo, in upstate New York, serving out a 15-year sentence.

Convicted in 2011 on a series of gun and drug-related charges, Coles’ story is a cautionary tale of greed, ambition, and the criminal trappings of Detroit’s underground gun market.

By all accounts, Coles, a community college dropout whose father was a convict, developed a plan that was brilliant in its simplicity. He’d use four young women — two of whom were cousins, one of them eight months pregnant — to drive illegal firearms fresh from Detroit’s streets into Canada via the Detroit-Windsor Tunnel, where they would be put on the black market for a tenfold markup.

By all accounts, Coles, a community college dropout whose father was a convict, developed a plan that was brilliant in its simplicity. He’d use four young women — two of whom were cousins, one of them eight months pregnant — to drive illegal firearms fresh from Detroit’s streets into Canada via the Detroit-Windsor Tunnel, where they would be put on the black market for a tenfold markup.

It all began to unravel for Coles, then 23, back in 2008, when a confidential informant passed on a tip to the ATF about a Detroit street-level gun dealer named “Dougie” who was looking to transport firearms into Canada.

Contributing to a 2013 Toronto Sun exposé detailing the ease with which U.S. guns make their way into Canada, Coles — who already had a record for drug and gun-related offenses when the ATF began tracking him — relayed to the paper through a prison-managed email system that he sought to avoid suspicion above all else. “I wanted to be as discreet as possible,” Coles said. “I figured it would be less suspicious if someone who didn’t have a criminal background (did) the transporting.”

For a time, his strategy worked perfectly — or so it appeared — as Coles moved 35 guns into Canada for $36,000 in profit over a four-month period. There was only one problem: Coles’ customers were, in reality, a combination of Canadian and U.S. federal undercover law enforcement agents.

Stateside, the ATF, courtesy of the informant’s tip, had been onto Coles’ operation for months.

Undercover U.S. agents, posing as Toronto drug dealers in the market for high-powered American guns, traced Coles’ cell number to his grandmother’s west side Detroit address, leaving virtually no doubt to his true identity.

After a series of back-and-forth communications, Coles was apprehended by the ATF on June 4, 2008, in a strip-mall parking lot along Jefferson Avenue after exchanging nine guns for 50,000 ecstasy pills with his Toronto contacts. Lamenting on his transgressions with the law, Coles, who claimed he was raised by his grandmother “in a Christian household of love,” chalked up the lawlessness that put him behind bars to poor decision-making.

“This was my first time ever being involved with gun smuggling,” Coles says. “It was in a period of my life that I was unbalanced, so I made unwise decisions.”

With a dozen years left on his sentence, Coles expresses regret for any role he had in inflicting emotional pain to mothers who have lost children to gun violence. “To hear of the suffering around the world is a heartache, but to know that I could’ve possibly contributed to the mourning of mothers is upsetting,” he says.

Whether or not U.S. Attorney McQuade’s long-term strategy will end up putting more people like Coles behind bars remains to be seen. In the meantime, those plying within Detroit’s black market for weapons remain resilient and aggressive. Few incidents in recent years highlight that more than a string of thefts that Arena recalls occurring on the outskirts of downtown Detroit near the Patrick V. McNamara Federal Building at Michigan and Cass avenues.

As Arena says, at lunchtime there were a number of restaurants that were being frequented by law enforcement officers up and down Michigan Avenue. Included among the patrons were federal agents who routinely housed high-powered weapons — namely assault rifles and rapid-fire semi-automatic handguns — in the trunks of their government-issued vehicles.

Arena says it didn’t take long for criminals doing surveillance in the area to take notice of their presence, and to pounce. “The bad guys caught on to that,” he says. “They were targeting the area because they knew it was frequented by law enforcement. Not only were they stealing guns (out of the trunks), they were stealing ballistic vests, too.”

The direct affront to law enforcement during the brazen robberies — pulled off in plain view of passing traffic — showed that criminals looking to keep guns moving on Detroit’s streets have no qualms about pursuing the game of one-upmanship against those bound by law to stop them.

Unfortunately for Detroit, the game all but ensures there will be more deadly and tragic consequences in a city that can ill afford them. db