Edward Voigt regarded the brewing business as the means to an end. So after leading his brewery to become Detroit’s industry front-runner by the late 1870s, Voigt — who had once been a sailor — turned to other ventures. He owned downtown real estate and a 150-acre farm west of Woodward Avenue. Envisioning a bonanza in the latter, he laid out the Voigt Park Subdivision in 1891, and it was incorporated into the city limits, establishing the nucleus of today’s Boston-Edison Historic District.

Although the streetcar ran on Woodward, Voigt Park seemed to anticipate the coming

automobile age. Boston and Chicago were designed as boulevards, and were richly landscaped. Deep residential lots had plenty of space for carriage houses and, later, garages. “This was designed to be an upscale neighborhood from the beginning,” says Jerald Mitchell, the longtime Boston-Edison historian. “We didn’t have odious religious covenants. We were a welcoming neighborhood.”

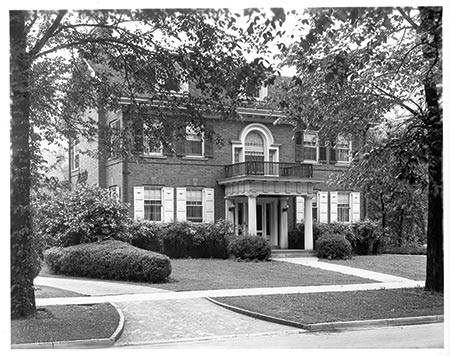

The Georgian Revival home of Albert Purdith, built at 120 Longfellow in 1904, was one of the earliest completed. More widespread construction started in 1905, right in the middle of a decade when Detroit’s population grew by about 60 percent. Architectural styles ranged from American eclectic to Tudor revival.

Albert Kahn Associates designed many of the houses, but other architects like Meade & Hamilton and Nathan Johnson had commissions, too. In 1911, three years after contractor Frank Goddard erected Henry and Clara Ford’s Italian Renaissance revival at 140 Edison, Goddard made extensive use of limestone in his own house at 751 West Boston.

Other affiliated subdivisions were developed, and Boston-Edison eventually encompassed a 36-block area that stretched to Linwood Avenue on the west, Boston on the north, Edison on the south, and Woodward to the east. Most of the 930 houses were completed by 1925. Restrictions stipulated uniform, two-story rooflines and at least a 30-foot setback from the curb. Lots spread up to 200 feet wide and 175.5 feet deep. Houses in Joy Farms, platted in 1915, had to cost at least $6,500 ($151,000 today). Brick and stone exteriors predominated; the only frame houses are found between Woodrow Wilson and Twelfth streets (the latter was renamed Rosa Parks Boulevard in 1976).

Reviewing the roster of original and succeeding residents is an enduring fascination. Horace Rackham, attorney and original Ford Motor Co. shareholder, lived in a 1907 American eclectic at 90 Edison. S.S. Kresge kept bees as a hobby at 70 West Boston, and clothier Benjamin Siegel’s 13,000-square-foot Italianate villa stood grandly next door. (Cousin Jacob and nephews Eugene and Joseph all lived within an easy walk.) At 101 Longfellow, Margaret Fisher, whose seven sons founded Fisher Body Co. in 1908, was situated near four of her boys, who owned manors on Boston, Chicago, and Edison (Charles, Edward, William, and Alfred).

In 1929, Ossip Gabrilowitsch, the Detroit Symphony Orchestra’s founding director, and his wife, mezzo-soprano Clara Clemens Gabrilowitsch, moved to 611 West Boston. Her father’s original manuscript of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer was found in the residence after it was donated to the Paulist Fathers in 1940. Included among later Boston-Edison residents were fighter Joe Louis (1683 Edison); Brace Beemer, radio voice of The Lone Ranger (1725 Chicago); Motown Records founder Berry Gordy Jr. (918 W. Boston); art dealer Joseph Dumouchelle (111 Longfellow); and Detroit Tigers slugger Willie Horton (112 Edison). A comprehensive list can be found online at historicbostonedison.org.

Construction of the Lodge Freeway, dedicated in 1957, diminished the feel of the neighborhood by dissecting it in half. And even a neighborhood as great as Boston-Edison — which became a historic district in 1974 — has been touched by blight. Mitchell says it “took a big hit” during the recent foreclosure crisis, but he says it’s coming back. Nevertheless, the claim made during the drive for historic status remains true: “The racial, ethnic, and economic diversity which hallmarks the history of the Boston-Edison area is equally present today.” db