The commercial real estate market recovery since 2010 in metro Detroit has led to new and proposed projects, while stoking the fortunes of owners and developers of office, industrial, retail, and hospitality (hotel) properties. Clockwise from upper left are a proposed industrial project in Wixom by CORE Parters; new shops and eateries in Birmingham’s Principal Shopping District; improved occupancy and room rates at hotels like MotorCity Casino in Detroit; and new offices for Jack Entertainment, the gaming operations of Dan Gilbert, founder and chairman of Quicken Loans Inc. in Detroit (along with a few partners). The office headquarters for Jack Entertainment at the former St. Mary’s School in Detroit’s Greektown was designed by Neumann/Smith Architecture.

In 2004, the sprawling, 1.1 million-square-foot complex at 2000 Centerpoint Parkway in Pontiac, known as Truck Product Center–Central, was a beehive of 4,000 employees responsible for engineering the entire truck line of General Motors Co.

Four years later, GM consolidated its engineers at its Warren Technical Center. TPC–Central, the home of the automaker’s most profitable vehicles and a showplace once befitting a meeting between former President George W. Bush and former GM Chairman Rick Wagoner, was empty. Underscoring the forlorn scene, the automaker — which filed for bankruptcy in 2009 — couldn’t afford to cut the lawn, and tall weeds overtook the once-packed parking lot.

At the same time, Macomb Mall, along Gratiot Avenue in Roseville, was suffering. The onetime fixture of east side shopping was 69 percent occupied; in 2011, its management was sued by the mall’s creditor for $42 million. The suit claimed, “The defendant has been unable to pay its utility and service bills and may have to shut down Macomb Mall,” according to news reports at the time.

“You had a lot of companies go bust in the (2008) recession,” says Adam Lutz, president and CEO of Q10/Lutz Financial Services in Birmingham and Detroit. “You had multitenant buildings go from 100 percent occupancy to 50 percent in months. Tenants would just move out in the middle of the night and landlords would try to pursue them through whatever means possible. It was a catastrophic environment.”

To the extent possible, the commercial real estate community tried to support itself during the hard times. Struggling tenants would appeal to their landlords, who might or might not step in, possibly negotiating “blend and extend” deals that shrunk payments in exchange for longer lease terms. No community in the region was immune to the economic carnage.

“During the recession it was a tenant-based economy,” says Andy Gutman, president of The Farbman Group, a large commercial property, management, and services firm in Southfield. “The landlords needed tenancy; the (inventory) was great, but the demand was not as great. We helped the landlords understand what it took to achieve tenancy — the number of months of free rent, the improvements that tenants expected, even the commissions that the brokerage shops were commanding at the time.”

Flash-forward to today, and the commercial real estate market has recovered more quickly than anyone could have anticipated. As national and regional economies grew, commercial real estate properties were lifted by the rising tide. TPC–Central’s current owner, California-based Industrial Realty Group, has since spruced up the property and signed contracts with tenants including Energy Power Systems, an advanced battery technology firm, and robot maker Fanuc America Corp.

In turn, Lormax Stern Development Co. in Bloomfield Hills acquired Macomb Mall in 2013, razed the vacant Crowley’s anchor store, built a 50,000-square-foot Dick’s Sporting Goods in its place, and added another 25,000 square feet of stores and restaurant space inside. Today, the mall is 96 percent leased.

“Commercial real estate in the region is benefiting from Detroit’s comeback, fueled largely by the auto and tech industries,” says Anthony Sanna, senior managing director and CEO of Integra Realty Resources, a national commercial real estate valuation, counseling, and advisory firm with an office in Birmingham.

“During the recession, most of the market thought it would take a couple of decades for Detroit and the metro region to get back to anywhere close to the national average (of vacancies and rental rates), but in seven short years, we are at or exceeding national averages on a lot of those metrics. We’ve come back with amazing vigor.”

Some parts of the commercial market are stronger than others, but according to IRR’s semiannual market study, which is based on 1,500 local property appraisals and other market research, the office, industrial, retail, and hospitality sectors have all surpassed their post-recession performance in terms of vacancy and rental rates.

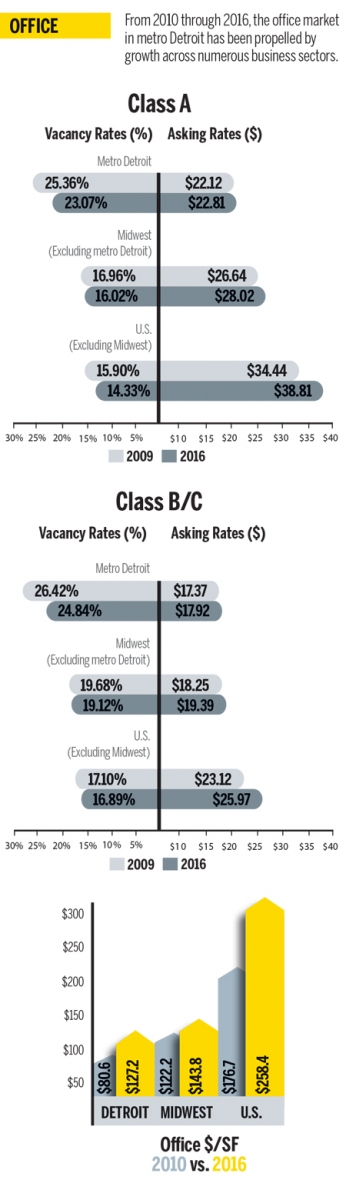

The IRR study found that average metro Detroit office rental rates are currently $19.10 per square foot, average metro office vacancies stand at 16 percent, and the office sale price per square foot is $108. In 2010, metro rental rates were $16.50, vacancies were 26 percent, and the sale price per square foot was $57 (see graphs).

The IRR study found that average metro Detroit office rental rates are currently $19.10 per square foot, average metro office vacancies stand at 16 percent, and the office sale price per square foot is $108. In 2010, metro rental rates were $16.50, vacancies were 26 percent, and the sale price per square foot was $57 (see graphs).

“That’s part of what’s driving the comeback of our region,” Sanna says. “There’s still great opportunity in this market because we’re so underpriced compared with other major metropolitan cities. Investors want to come into this region because of the upside opportunities they see here.”

The IRR study found similar gains from 2010 to 2017 in other areas. In the industrial sector, average metro rents increased to $5.50 per square foot from $4.50. The average vacancy in the region’s retail market dropped to 8.5 percent from 17.4 percent, while daily hotel rates in southeast Michigan increased 25 percent, to $99 from $79.20. Average rents and vacancies in the multifamily sector also improved.

According to the Detroit Regional Chamber’s 2017 State of the Region report, 1 million square feet of office space and 2.5 million square feet of industrial space were under construction at the end of the third quarter of 2016.

From office and retail to industrial and hospitality projects, the region’s commercial real estate landscape is growing — and changing. Workstations still exist, but shared spaces are gaining popularity with young workers, while auto suppliers require new concepts for engineering and R&D centers. Developers also must determine which retailers are still relevant in the age of Amazon. And millennials want to work and live in urban districts.

While most of southeast Michigan can boast of some measure of growth in the commercial real estate sector, Detroit’s central business district is arguably the most impressive in terms of sheer numbers. That’s due, in large part, to the vision of Dan Gilbert, founder and chairman of Quicken Loans Inc., who in 2010 moved 2,600 workers to downtown Detroit from different locations in the suburbs. Since that time, Gilbert and his Bedrock real estate venture have acquired 95 downtown buildings and filled them with high-profile tenants: Ally Financial moved from Southfield to Bedrock’s One Detroit Center on Woodward Avenue; Lear Corp. opened its Innovation Center last October in Capitol Park; and New York-based WeWork is opening shared workspaces — from a single desk to an eight-person office — in Bedrock’s building at 1449 Woodward Avenue, as well as at the 1001 Woodward building bordering Campus Martius Park.

“Our future plans are to keep this momentum going, not just with our own acquisitions and development, but with our continued encouragement of other developers making the same or similar investments in the city,” says Bedrock CEO and co-founder Jim Ketai.

With its “28 Grand” project, a new 13-story, 101,000-square-foot residential development at 28 W. Grand River Ave., Bedrock hopes to catch the micro-loft wave. The project features 218 furnished apartments, and each offers around 260 square feet of space. “Urban dwellers use the city as their kitchens and living rooms,” Ketai says. “They come to their apartments to charge their phones and sleep.”

Finding office space in the suburbs, meanwhile, is a matter of what you need and how much you’re willing to spend.

“You’re clearly seeing the trend to ‘urban-walkable’ in Detroit and micro markets like Royal Oak and Birmingham,” says Eric Banks, principal, board member, and a partner at CORE Partners, a commercial real estate firm in Bingham Farms. “In Royal Oak, demand for office space had, for years, outstripped supply. Finally you’re seeing major market developers coming in two or three at a time looking to build mixed-use buildings there. Renters can afford and are willing to pay higher rental rates — $30 per square foot in Royal Oak and pushing $40 in Birmingham — which is a prerequisite for any new construction.”

CORE Partners and Burton-Katzman Development Co. in Bingham Farms are collaborating on an 80,000-square-foot office and retail building, along with an adjacent 150-room boutique hotel, on Main Street in Royal Oak, just south of the train tracks. Etkin Equities Inc. in Southfield, meanwhile, is developing a 74,000-square-foot office center near Main and 11 Mile Road. Another developer has proposed replacing the city’s Centre Street Garage with a hotel, residences, and a new parking deck, while the Royal Oak City Commission is in talks with a consortium of partners to build a $100 million mixed-use development that includes a new city hall.

Dave Miller, principal at Signature Associates in Southfield, says the current trend in office layouts is 25 percent traditional and 75 percent open plan. “People are emailing instead of calling, so noise isn’t a factor; millennials are collaborative and they like the socialization; and you can get more people per square foot when you don’t have walls,” Miller says. He says the standard office layout allocates 250 square feet of gross building area per employee, but some offices are “densing down” to 125 square feet or 100 square feet because many employees spend so much time away from the office.

Farbman’s Gutman says few new office buildings have gone up in recent years because the cost is still too high. But if the market can’t handle brand-new inventory, the next best thing is amenities.

“We’re seeing a flight to quality,” Gutman says. “People want nice finishes and building amenities (in existing facilities). Many landlords are building out fitness centers and shared conference rooms. In buildings that can accommodate them, you’re seeing convenience stores, restaurants, and the growth of collaboration and common areas — a kitchenette that can double as a conference center or a ping pong area.”

In turn, Gutman is in discussions with Oakland County Treasurer Andy Meisner, who counseled the city of Pontiac on its January 2017 sale of the Phoenix Center parking structure and adjacent Ottawa Towers office buildings to BoonEx, an Australian-based software company, for a reported $3 million.

“The county has been working so hard to try to revitalize Pontiac,” Gutman says. “For investors who might be priced out of the city of Detroit, I think Pontiac presents the next best opportunity. I’ve never seen this with a government official before, but Meisner has been literally taking people on walking tours of all the vacant buildings and showcasing what might be available from the government.”

Troy also is sharing in the commercial growth, but not quite like Royal Oak and Birmingham. The city boasts 21 million square feet of office space, but its vacancy rate in 2016 was 17 percent — not as healthy as other parts of the region, but down from 35 percent vacancy in 2010.

“Cities that have large office buildings were impacted significantly in the recession,” says Glenn Lapin, Troy’s economic development specialist. “Troy had huge buildings going (up in) the ’70s and ’80s, but then the economy started shifting. A lot of the offices in northern Troy were built for EDS Corp., and when a big company like that packs up their bags, that leaves all the extra space. That’s why vacancy got to be 35 percent or higher during the recession.”

Still, Troy has been successful in recent years, attracting some 200 new businesses. “We’re seeing growth from several sectors,” Lapin says. “Advanced automotive and related technology continues to be strong,” with such new entries as Karma Automotive, Mahindra North America, Tyler Technologies, and tech firm Royal DSM.

Lapin credits the city’s privately run permitting and inspection services, as well as updated zoning ordinances, with attracting new office users. “Under the old ordinances you could only do offices in one place, industrial in another, commercial in another,” he says. “Now you can use industrial areas to do anything you want, except to build single-family homes. That’s part of being business-friendly.”

In January, real estate services firm Cushman and Wakefield announced that U.S. industrial markets absorbed 63.6 million square feet of space in the final

quarter of 2016, propelling net absorption for the year to a record-setting 282.9 million square feet of space.

“The current industrial expansion is one for the record book,” Cushman and Wakefield said in a press release. “As of January 2017, the industrial sector has registered 27 consecutive quarters of net occupancy gains, placing this expansion among the longest ever.” The firm said the national industrial vacancy rate for all product types continued to decline in the fourth quarter, falling to 5.5 percent.

“The current industrial expansion is one for the record book,” Cushman and Wakefield said in a press release. “As of January 2017, the industrial sector has registered 27 consecutive quarters of net occupancy gains, placing this expansion among the longest ever.” The firm said the national industrial vacancy rate for all product types continued to decline in the fourth quarter, falling to 5.5 percent.

“We were almost overbuilt 10 years ago and now we’re underbuilt, even with 230 million square feet of industrial inventory,” says IRR’s Sanna. “In 2010, the average vacancy in metro Detroit was 18.5 percent; today we’re at 8 percent. The trend toward autonomous vehicles and mobility technology is quickly finding a niche in the Detroit market as design, engineering, and test facilities are established. We expect this trend to continue for the next two to five years.”

Industrial is the story of the resurgence of the auto industry, says Justin Robinson, vice president of business attraction at the Detroit Regional Chamber. “The last three years have been the best and most profitable for the auto industry and we’re reaping the rewards,” Robinson says. “From 2010 through 2015, Michigan has received $26.7 billion in OEM and supplier investment.”

But as demand for industrial space is ramping up, the available inventory is lagging.

“We have 2 percent vacancy in some of the hotter markets,” Robinson says. “The demand for high-quality, well-situated industrial space is at its peak and its supply, unfortunately, is at a low. As a result, many of the companies are taking smaller spaces that have to be renovated, or they’re having to do ‘build-to-suits.’ Currently I only know of four developers doing spec development in our market.”

Robinson says more companies might have to consider following the example of Durr Systems Inc., which converted a former DTE Energy call center in Southfield into an R&D and engineering center.

Retail developers and their clients also are benefiting from post-recession prosperity, but not all shopping venues are created equal. “The big trend now is the change in the way people want to shop,” Sanna says. “You’re seeing smaller, functional retail and strip centers along places like Hall Road and Big Beaver Road, usually around 10,000 to 20,000 square feet in size, and typically closer to the road with unique architecture. The metro Detroit market currently contains about 100 million square feet of retail space — 125 million square feet, if shopping malls are included.”

According to retail management software firm Vend, consumers don’t want to waste time wandering endless aisles of enormous stores. Instead, they seek out the ease and efficiency of smaller stores with specialized selections. Even big box giant Target Corp. plans to open hundreds of smaller “flex format” stores — less than 50,000 square feet in size — around the country, as part of its growth strategy. A Target spokeswoman says the company has no plans to build any of its smaller locations in Detroit, although “Target continuously explores possible locations for future stores.”

Chris Brochert, co-founder and partner at Lormax Stern Development Co., says retail space isn’t growing like it did in the past. “Since the crash,” he says, “where else have you seen any major retail development being built in the area other than a free-standing Kroger or Meijer with out-lot pads (in the parking lots) being built right up to the streets?”

Chris Brochert, co-founder and partner at Lormax Stern Development Co., says retail space isn’t growing like it did in the past. “Since the crash,” he says, “where else have you seen any major retail development being built in the area other than a free-standing Kroger or Meijer with out-lot pads (in the parking lots) being built right up to the streets?”

For Brochert, the alternative to building new is renovating existing properties. “We bought the Macomb Mall in 2013 for a very reasonable price. The closest malls, Partridge Creek and Oakland Mall, are 10 miles away. It’s a very densely populated area and people didn’t have anyplace else to go.”

Lormax Stern renovated the interior of Macomb Mall, changed the pedestrian traffic patterns, took out “garbage tenants” — stores that sold cigarettes, disposable cell phones, or lottery tickets from kiosks — and came up with a list of retailers like Rue 21, Ulta, and Bath and Body Works. “We wanted the best retailers who’re going to succeed, rather than just the guy who’s going to pay the most money,” Brochert says. “We had the first phase of the renovation done by Christmas 2014. The second phase was done in 2015, and our sales were up 50 percent. We have tenants on waiting lists.”

Lormax Stern also demolished Livonia Mall in 2009 and reopened it as Livonia Marketplace I in 2010 with Walmart, Kohl’s, Petco, and other stores.

Ron Gantner, a partner at Plante Moran Cresa, which has offices in Southfield and Detroit, believes retail as a destination is also a growing trend. “The Somerset Malls of the world are going to continue to exist because of the location and the experience,” he says. “Outlet malls like Great Lakes Crossing draw people with aquariums and movie theaters. Cabela’s in Dundee is a great example. It’s in the middle of nowhere, but people are going to drive there because of the experience.”

Gantner says The District Detroit, the downtown development that includes the new Little Caesars Arena that is scheduled to open in September, is being built with an eye toward an overall experience. “The game or the event is part of that experience, but you want to get people down there two or three hours ahead of time and create an environment that’s unique and exciting, and hopefully they’ll stay there afterward,” he says. “When’s the last time you bought a CD at a store? But Third Man Records (musician Jack White’s record label, which partnered with Shinola in 2015 to open a retail store on Canfield Street in Midtown) is creating an experience. You go into (the store) to touch and feel (the merchandise), play with the vinyl, and see neat things you can’t see anywhere else.”

As the region’s economy continues to grow, so does demand for hotel rooms. For example, the Foundation Hotel, a 100-room lodge opening this year in the former Detroit Fire Department Headquarters across from Cobo Center, is one of dozens of new properties hoping to share in the city’s prosperity. There’s also Bedrock’s recently announced 130-room Shinola luxury boutique hotel on Woodward Avenue in downtown Detroit that’s set to open in the next two years.

“The hospitality/hotel industry in southeast Michigan has recovered quite nicely from the Great Recession,” says Ron Wilson, CEO of Hotel Investment Services in Troy. “(The year) 2015 was probably the best year overall between occupancy and average daily rate increases, with 2016 arguably being the second-best year.” He adds that from 2008 to 2010, the only hotels that opened were those that were already funded and in the pipeline. After a breather of several years, capital markets cautiously opened up and hotel development took off.

“At the start of 2016, over 30 hotels were in development in southeast Michigan,” Wilson says. “That is moderating now because capital markets are starting to tighten up again and we’re not seeing that much growth in occupancies. Banks are starting to dial back to see how that supply gets absorbed. Where deals were getting done with 70 or 80 percent leverage, now it’s 50 or 60 percent. Interest rates are starting to move up.”

Hospitality is a sector where investors can make a lot of money or lose a lot of money in a very short time because income is on a daily basis and is based on occupancy, says Kevin Jappaya, president of KJ Commercial Real Estate Advisors in Farmington Hills. “We had good equity in our deals and never really faced any turmoil during the recession,” he says.

Hospitality is a sector where investors can make a lot of money or lose a lot of money in a very short time because income is on a daily basis and is based on occupancy, says Kevin Jappaya, president of KJ Commercial Real Estate Advisors in Farmington Hills. “We had good equity in our deals and never really faced any turmoil during the recession,” he says.

Since 2011, KJ Commercial has spent $13 million purchasing and renovating hotels in Houghton Lake, Sault Ste. Marie, and St. Ignace. Jappaya also acquired land in Taylor, near Southland Mall, and will build a Home2 Suites hotel by Hilton, investing another $11 million.

KJ Commercial also represents developers and has sold more than a dozen sites in the past three years for new hotel construction. “There was opportunity with different franchise systems that had missing placements in different communities just because there was a lag in new development for many years,” he says. “If you were a partner with Marriott, Hilton, or IHG, they have a strong following and they perform very well in these new markets.”

What’s more, the region’s commercial real estate sector is bullish on the future. “We’re outperforming the Midwest in almost every property sector,” Sanna says. “Our trajectory is solid and we have diversification in industry. Autonomous vehicles and mobility are the real deal. I think we’re going to benefit from the Trump bump, with some deregulation and Dodd-Frank being watered down. I think we’re poised for a really robust 2017, 2018, and 2019.”

Still, investors eyeing Detroit and other cities in Michigan for large-scale projects say the market needs assistance with overall funding. To that end, the Michigan Legislature is reviewing a tax increment financing plan that would allow for more large mixed-use projects. “There’s no question the legislation is needed, especially on brownfield sites that need to be cleaned up and put back to productive uses,” says Joel Smith, president of Neumann/Smith Architecture, which has offices in Detroit and Southfield.

For smaller projects, today it’s easier to finance buildings in Detroit and other urban districts, says Bedrock’s Ketai. “Money’s coming from banks, credit unions, venture capital, and overseas. I absolutely see this sustaining itself. I think we’re actually very early on in this uprise era. Artists and retailers and tech people are realizing that if you live in Detroit, if you start a company here, you really have the ability to make a difference, to be a part of this growth. We’ve come a long way and we have a long way to go. There’s lots of room to still grow. I don’t see us in a bubble at all.”